ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Courtroom Artists’ Rogues Gallery

Jeffrey Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, Bernie Madoff—when cameras are banned, artists capture the key characters in the nation’s most notorious trials.

By Suzanne Charlé

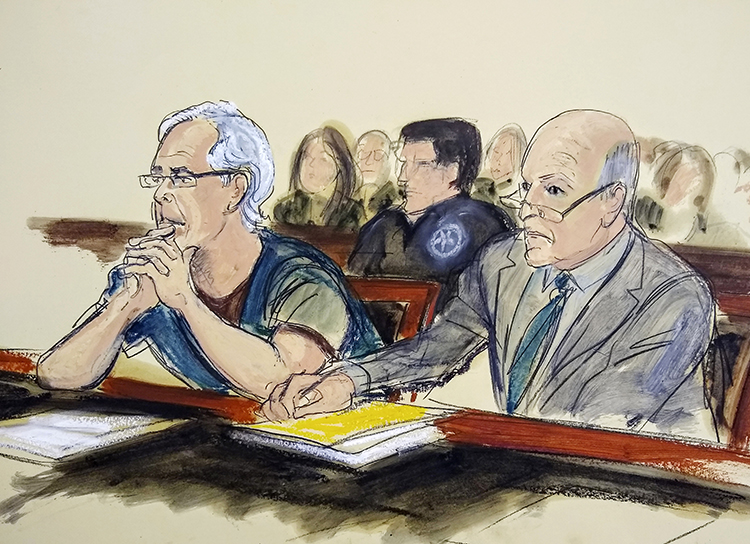

In Elizabeth Williams’ courtroom sketch, defendant Jeffrey Epstein, left, and his attorney Martin Weinberg listen during a bail hearing in federal court, Monday, July 15, 2019 in New York. Client: Associated Press.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

On a hot mid-July day, Jeffrey Epstein, clothed in a blue jailhouse jumpsuit, sat in Manhattan’s Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse, hoping to be released on bail. The courtroom was packed: People had been waiting for hours for a glimpse of the wealthy investor, charged (again) with child sex trafficking, and they craned forward to see if he would be allowed to return to his Upper East Side mansion. Among the most attentive were a half-dozen artists, sitting in the jury box, swiftly, silently sketching the scene, taking it all in: Epstein, his lawyers, the prosecutors, the judge and two young women who accused him of sexually abusing them when they were children.

U.S. District Court Judge Richard Berman’s summary was as brief as the wait had been long: Epstein’s collateral—his $77 million mansion, where prosecutors said he abused dozens of underage girls, and a private jet—was “irretrievably inadequate.”

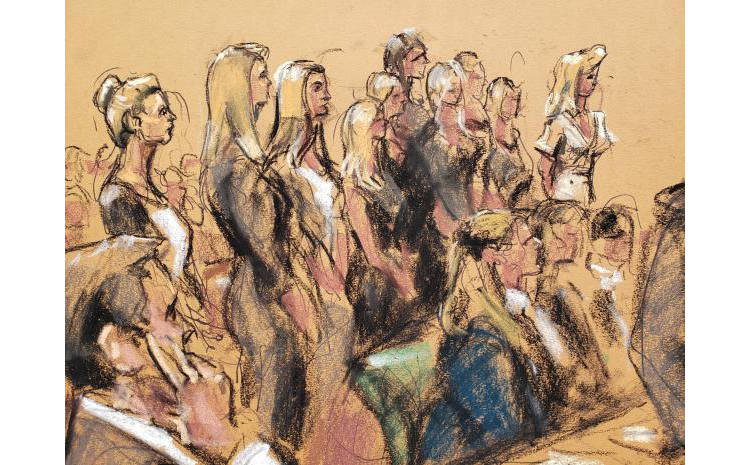

Jane Rosenberg’s sketch of Jeffrey Epstein’s accusers in a NYC courtroom, August 27, 2019.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

“I doubt that any bail package can overcome the danger to the community,” Judge Berman declared. In less than 15 minutes, the judge had left the courtroom and Epstein was led back to the Metropolitan Correctional Center. Only the artists remained, working as fast as possible before being kicked out by a deputy.

Six weeks later, the illustrators were back in court as Judge Berman presided over an unprecedented two-and-a-half-hour hearing. Epstein had somehow managed to hang himself while in jail; now, 23 women detailed how he had abused them and the trauma that lingered. In tears, one pleaded, “the reckoning must not end.”

Illustrators have been recording important American cases for over 150 years, including the 1865 trial surrounding Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. But since the 1990s, most courts have opened their doors to photographers; Federal courts are the last bastions open only to court artists.

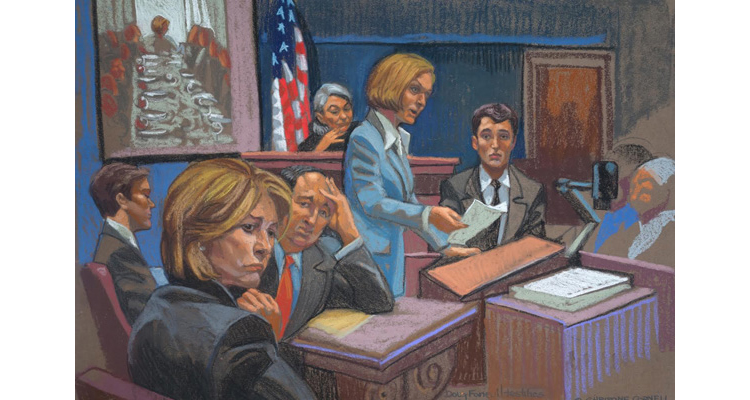

Christine Cornell’s sketch of Martha Stewart’s securities-fraud trial. Stewart—shown, at left, as her attorney looks on with his hand to his head—was sentenced to five months behind bars.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

For all that, there is work for the half-dozen artists who are regulars at New York’s district courts: Wall Street offers up a goodly share of white-collar crime, while the regular streets contribute murder and other types of mayhem. Armed with ink and pen, pastels and watercolors, they document key moments and figures in the nation’s most infamous crimes: insider trading by the likes of Ivan Boesky, Michael Milken, Raj Rajaratnam, and Martha Stewart; sexual assault by financial figures like Dominique Strauss-Khan; high-profile shenanigans by big names in politics and Hollywood, including Imelda Marcos, Woody Allen, and Harvey Weinstein, and grizzly acts by terrorists including the World Trade Center bombers.

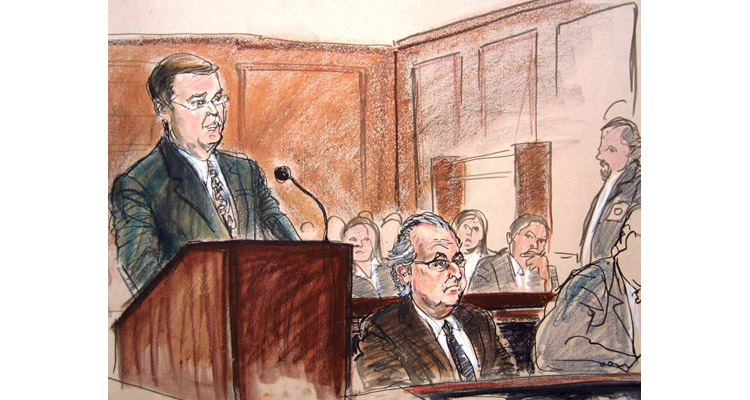

Aggie Kenny sketched the Mitchell Stans trial. Rosemary Woods, former Richard Nixon secretary, is on the stand.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Here in New York City, the six artists who frequent the Moynihan Courthouse are women. “There used to be a lot more, and many men,” says Elizabeth Williams, who explained that as television news expanded in the 1960s, so did the need for artists who could cover the crimes. The heydays were between 1964 and 1994, when banner headlines blared with crime and criminals: serial killer Son of Sam, mob boss John Gotti, the whole Watergate cast of characters.

Aggie Kenny, the veteran of the group, won an Emmy for her coverage for CBS of the John Mitchell-Maurice Stans trial, which included the testimony by FBI deputy director Mark Felt (later revealed as “Deep Throat”). Kenny is known for deftly capturing the attitudes of key characters, as exemplified by her water color of a haughty but disheveled James Earl Ray, when the assassin of Martin Luther King Jr. attempted to recant his earlier guilty plea. “His hair was awry all the time, and when he crossed his legs, it would reveal white socks and skin. From his gestures, it was clear he was uncomfortable.”

Aggie Kenny’s sketch of Angela Davis representing herself, seated at trial in San Jose 1972.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Of all the defendants she has drawn, Angela Davis most impressed her. It was 1972, and the young illustrator had been sent out to California where the UCLA professor was on trial for murder, conspiracy and kidnapping. “She defended herself,” Kenny recalls, who adds that she was struck by Davis’ poise and self-assurance, declaring her innocence and presenting the facts in front of the all-white jury and judge—a poise evident in Kenny’s depictions.

These illustrators combine the intelligence of a journalist and the skills of an artist, all under extreme deadlines. They do, however, differ in how they approach their work. Williams, who regularly works for the Associated Press, only draws what a photographer could shoot. Often, that limits what can be shown: either the faces of the defendant and his lawyers or the judge and whomever is close by: “Only what’s in front of me.” Such keen focus can be riveting, as when the financier Bernie Madoff, charged with bilking investors of billions through his Ponzi scheme, was denied bail and was led out of the courtroom, in handcuffs, by federal marshals. “The door was open, and because of where I was sitting, I could see the bars of the cell,” says Williams, adding that it happened so fast, she almost missed it.

Elizabeth Williams’ sketch of the Bernard Madoff hearing. Client: Bloomberg News.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Other outlets have no such requirements, and most artists are glad of it. Jane Rosenberg, who has been in the courts since 1980, sometimes manages to get in everyone in her pastel and pen-and-ink drawings: during the custody hearing, she condensed Allen Dershowitz, Woody Allen, Mia Farrow, the judge and Allen’s attorney into one image.

The view was similarly compressed and compelling in 2004 when Martha Stewart was sentenced to five months behind bars for securities fraud. What photographers can shoot, Rosenberg says, “is for photographers.” “If I can catch the action, the emotions and drama going on, I’m happy with what I’ve done!” (During General Westmoreland’s trial in the early 80s, she even drew eight court reporters sketching away—including herself in the front row, second from the left.)

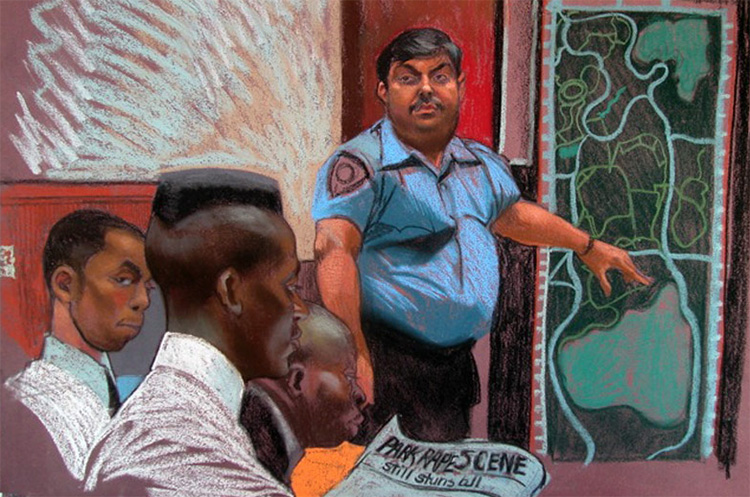

Christine Cornell sketched the Central Park Five trial: An officer shows the location of the crime, and a newspaper headline reads “Park Rape Scene still stuns all.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Christine Cornell, whose drawings of the original Central Park jogger trial appear in Ken Burns’ documentary “The Central Park Five,” frequently uses binoculars to capture the telling details of the people she’s drawing: Harvey Weinstein, when he appeared in court last June, Anthony Weiner breaking down when he was sentenced in September 2017.

“Often, I’ll have to move to be able to see around marshals and others, or defendants who don’t want to show their face,” she said. Last September, she managed to catch Bill Cosby, as he jumped up and swore at the prosecutor, while supporters tried to calm him down. “It was so fast and chaotic, I wasn’t certain at first who was yelling.”

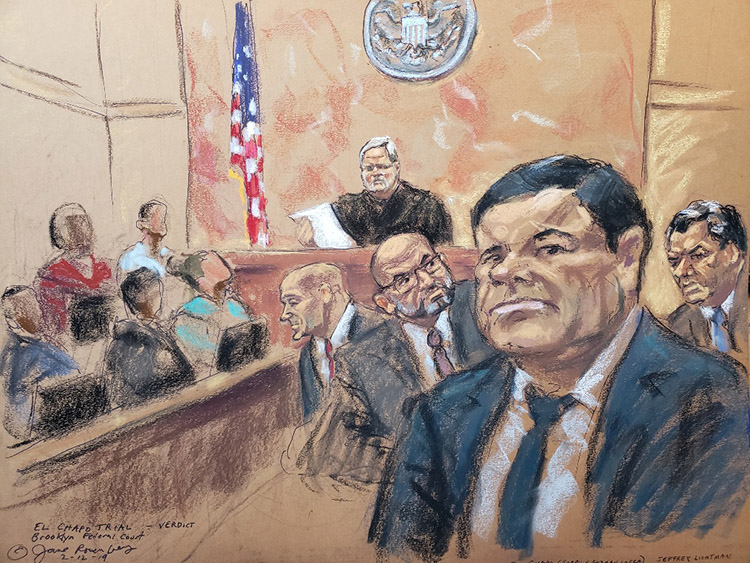

One of Jane Rosenberg’s drawings of the El Chapo trial.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

First come, first served for El Chapo, and Michael Cohen

It’s been a busy summer for the artists, who’ve stood on line for hours, waiting to begin their work. “It’s first come, first served,” explains Aggie Kenny. “The worst,” says Rosenberg, “was El Chapo.” To capture the Mexican drug lord’s sentencing, she got on line at 3:45 a.m., armed with art gear and sleeping bag. Elizabeth Williams, who lives in downtown Manhattan, has what might be termed “home court” advantage: She was the only artist to make it to court when Michael Cohen pled guilty to committing campaign finance violations and implicated Trump. “Robert Mueller was mum on everything. The notice came out that ‘John Doe’ would appear that morning; I was up and ready to go in a half an hour.”

As for the timing of upcoming assignments? “Who knows?” says Williams. Movie mogul Harvey Weinstein’s trial for rape and sexual assault was just pushed back to January. The sentencing of Akayed Ullah, convicted of terrorism for setting off a bomb at the Port Authority/ 42nd Street subway, is scheduled for September 10th, “but will the editors will think it’s important?” And then there are the various trials relating to associates of Epstein and Trump. “You just can’t predict from one day to the next.” That’s why Williams and the other artists all have other gigs: weddings, conferences, other art projects including documentaries—all endeavors that have solid schedules, unlike the ever-changing calendar of federal courts.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

You can see over 100 works by Liz Williams, Jane Rosenberg and Aggie Kenny in “History Through Art: An Exhibition of 35 Years of Courtroom Art,” on display in the main lobby of the Moynihan U.S. Courthouse, 500 Pearl Street, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays. There will also be an exhibit at the National Arts Club, with a panel discussion on November 1. For a deeper dive, read The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art, by Elizabeth Williams and Sue Russell, which won Kirkus Reviews’ Best Book of 2014.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including the Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the magazine. She has co-authored many books including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

You may enjoy other NYCitywoman articles by Suzanne Charlé:

Apollo 11: Fifty Years After the Giant Leap

Just in Time: The Statue of Liberty Museum

The Bookshop Band: A British Institution

New York Splendor: Luxurious Rooms

Activist Artists Focus on Politics Past and Present

The Notorious Ruth Bader Ginsburg