ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget … My Friendship with Seiji Ozawa

Rehearsing Mozart and Bizet with the late Japanese superstar conductor in Tanglewood and Tokyo

By George Gelles

Debut: Seiji Ozawa’s first performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood on August 16, 1964. Photo by Heinz Weissenstein, Whitestone Photo and the BSO Archives.

February 12, 2024

February 12, 2024

Seiji Ozawa, who died on February 6th at age 88, has been much on my mind lately as I’ve recalled our times together and prepared the reminiscences that follow. I last wrote to him three years ago, wishing him well on his 85th birthday. Tatsu, his able assistant, answered, saying that Seiji received and appreciated my email, but that I shouldn’t expect a personal reply—so poor was his health. Sharing the sadness felt throughout the music community, I feel deeply privileged that Seiji had spent some of his time with me. The memories here seem more poignant.

Over years of concertgoing, I heard more than my share of great performances: Among myriad others, there was Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic in an impassioned Brahms Second Symphony, kicking the orchestra into overdrive for the finale’s last few measures; Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, pianist and tenor and partners for life, performing as one in recital; Vladimir Horowitz dazzling at the piano in an infrequent, typically idiosyncratic recital; and the Metropolitan Opera at its peak, performing Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, a production designed by the great South African artist William Kentridge, with a brilliant cast led by James Levine.

But the most indelible performance of all is one in which I participated. At age 17, I was one of five French hornists chosen to perform at the Berkshire Music Center (BMC)—the summer congregation of fledging professionals who convene at Tanglewood to be tutored by members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO). The program was established in 1940 by Serge Koussevitzky, then music director of the BSO, and though its name and faculty have changed—it’s now the Tanglewood Music Center, and its mentors include both BSO members and other luminaries—its mission remains unchanged: to foster community and enhance excellence among musicians of all ages and backgrounds.

At the session’s start, I met a fellow student who became a colleague for the summer and beyond. This was his first visit to America from his Japanese homeland, and he was at Tanglewood to study conducting with Charles Munch, the BSO’s music director. Thanks to an alchemy I can’t divine, Seiji Ozawa and I forged a friendship that lasted for more than a half century.

The BMC orchestra was the main event for instrumentalists; elsewhere on Tanglewood’s lush campus, singers sang and composers composed. For the first concert Seiji conducted in America, fortune smiled on me—I was assigned to be first of the two hornists in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364. Composed in 1779 and scored for violin and viola soloists and orchestra, the work is a classical hybrid that weds aspects of concertos with features of symphonies, and is Mozart at his prime—the word heavenly comes to mind. Our violinist was Charles Treger and the violist Jesse Levine, both of whom would go on to enjoy world-class careers.

Seiji, however, stood out. Though still in his mid-20s, he already had it all. His musicality was genuine and his energy palpable. There was a freshness to his music-making that you rarely encountered among conductors of any age, and it was a freshness he never lost. He had a warm rapport with his musicians, and communication, the flow of feelings, was nonstop.

You didn’t want to give Seiji 100 percent; you wanted to give him more. He elevated our performance, as the best collaborators can, and he had the audience enchanted, and why not? They knew they were hearing something special.

I’ve seen only one comparable artist in a somewhat similar situation. Mikhail Baryshnikov, shortly after defecting from Russia to the West in 1974, gave his first American performance with the American Ballet Theatre at the Kennedy Center Opera House in Washington, D.C., and his appearance was electric. It was whip-smart, and animated with extraordinary energy. In Russia, his performance schedule was limited both because of his height—he didn’t have the stature of the classical danseur noble—and because he favored Western ballets over Soviet standards. Now, it seemed, emotion and energy burst out. It brought to mind Seiji. Only a few years of age separated Seiji and Baryshnikov when they first appeared in America, and their debuts added new stars to the artistic empyrean.

Shortly after our summer at Tanglewood, Seiji found a mentor in Herbert von Karajan, the music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, and fortuitously, while he was there, I won a fellowship to study at the Free University of Berlin. There was time to pal around, to discuss music, to solve the world’s problems. Seiji was somewhat older and far more urbane. I learned from his musical insights, and also was the beneficiary of more practical matters: My introduction to Japanese cuisine was courtesy of Seiji, when we visited a restaurant in Berlin’s City Center. It was sushi in the shadow of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche—the bombed-out cathedral regarded then, as now, as a memorial to World War II.

Fast-forward several decades. Seiji enjoyed vast success, serving as music director of the Toronto Symphony, the San Francisco Symphony, and most notably the Boston Symphony, where his 29-year tenure is still unmatched and will likely remain unequaled. The orchestra business has changed, and today’s conductors are journeymen and -women, less likely to put down roots, ever on the move.

Seiji’s success was not unalloyed. Standing on principle, he several times dealt with personnel issues: in the 1960s with the NHK Symphony, Japan’s premier orchestra; in the 1970s with the San Francisco Symphony; in the 1990s with the Tanglewood Music Center. To an outside observer, each of his actions seemed defensible and well within the scope of music-director prerogatives. Others disagreed.

Over the years, I was among the legion of Seiji’s admirers, and enjoyed his performances—sometimes in person, more often on recordings; his recorded repertory was vast, embracing Mozart and Messiaen, Beethoven and Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev, Berlioz and Ravel. As for me, I had to acknowledge that I didn’t have the fire in my belly to pursue a professional career as a hornist. For those who do, I have endless regard. Yet I was fortunate to perform under other great conductors whose surname wasn’t Ozawa, including Charles Munch and Simon Rattle. Playing horn or not, I always aimed to contribute to the field, and I had many opportunities to do so, primarily as executive director of Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra in San Francisco, as program officer with the Ford Foundation’s Office of the Arts, and at the National Endowment for the Arts. And, of course, as an observer and writer on music and dance.

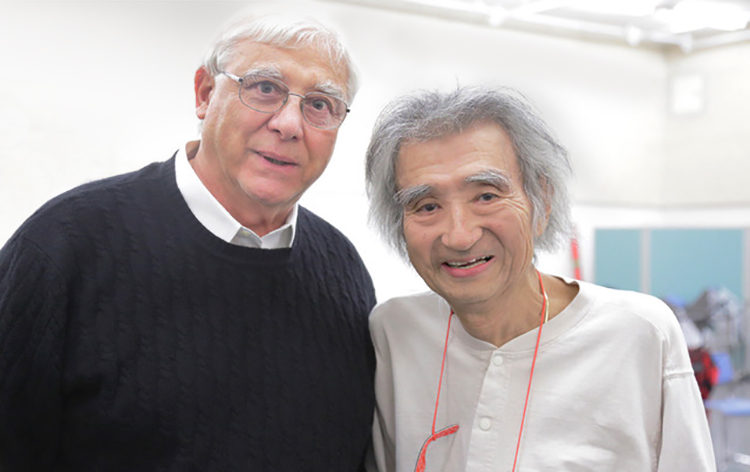

A lasting friendship: George Gelles and Seiji Ozawa in Tokyo, 2019.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Then, five years ago, I had an opportunity to visit Tokyo, Seiji’s home, once again. That he had been seriously ill with cancer was common knowledge, over several years requiring multiple surgeries, with concert appearances canceled. We had lost touch.

Before arriving in Tokyo, I wrote the email of a supplicant—“Dear Seiji: You probably don’t remember me…”—but had no email address for the would-be recipient. I was acquainted, however, with a prominent member of Japan’s corporate community who seemed to know everyone. “Masashi,” I said, “if anyone can find Seiji, you can.” That evening, my hotel phone was flashing when I returned from dinner. It was Seiji, who of course remembered me; friendships can outlast most anything. He suggested that I meet him the following day as he rehearsed Bizet’s Carmen. When I arrived, Seiji stopped the rehearsal, and we greeted each other with the obligatory man-hug and grabbed some quick conversation. He was sorry, he said, that I missed the rehearsal of the opera’s “Smugglers’ Quintet”—a piece he much enjoys. When he recorded it years earlier (heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3rI7cn3eyA at 16:19), a critic noted that it “fizzes along with elegance and esprit.” The earlier run-through, which I hadn’t heard, had greatly pleased him. “Maybe,” Seiji said, “if there’s time….”

The rehearsal was remarkable, without any signs of diminished brilliance. He would be touring Carmen the following month, but only in Japan, and this abbreviated itinerary was perhaps the sole concession made to his earlier illness.

At the conclusion, Seiji addressed the musicians in Japanese. When they faced me with polite applause, I realized he had explained who I was and why I was there. Then, still on the podium, he lifted his baton, said, “For George,” and led his musicians in a reprise of the “Smugglers’ Quintet.” In that moment and ever since, l’ve been touched to tears by Seiji’s generous gesture. Will I always remember? How could I ever forget?

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles has also written about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: