ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

A Mozartiana Extravaganza

Mozart festivals, Mozart books, Mozart in Salzburg, Mozart in Vienna, Mozart gifts—even Mozart music

By George Gelles

Dec. 12, 2023

Mozart means magic. And Mozart means marketing.

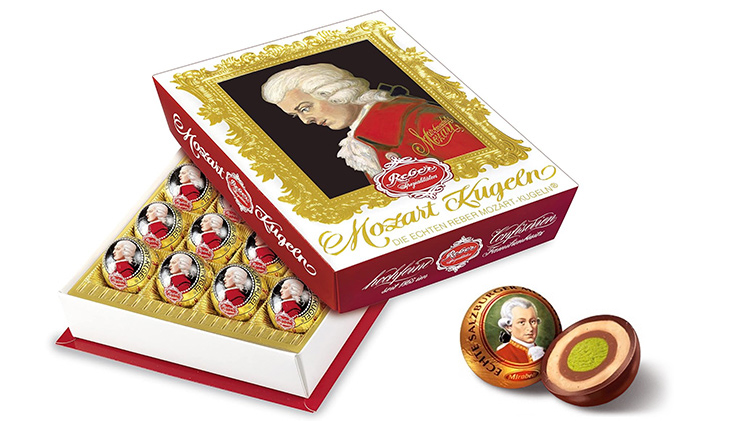

Let’s start with the Mozartkugel—the Mozart Ball—which was introduced in 1890 by the Salzburg confectioner Paul Fürst. To me, it’s the king of candies—marzipan covered with nougat, then enrobed with dark chocolate. Fürst was first, but now at least nine competitors claim the sweet’s invention as their own.

Also from Salzburg comes Mozart Chocolate Liqueur, in an array of flavors: dark chocolate and white, chocolate with coffee, pumpkin, or strawberry. The drink of choice, of course, its recipe online, is a Mozartini.

Cheers! The Mozart Chocolate liqueur (“Dark” version). Poured to the brim of a cocktail glass. Photo by Kike Salazar N.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

How about a smoke? Mozart Cigars, manufactured between 1912 and 1955, were once the rage, and they, or any stogies, can be housed in top-of-the-line humidors called The Mozart, “classic and elegant.”

If you’ve visited Austin, TX, you’ve surely been to Mozart’s. The lakeside coffeehouse is equally devoted to mocha and Mozart, with weekly concerts a menu staple. While there, you can purchase Mozart T-shirts, Mozart coffee mugs, Mozart baseball caps, and Mozart’s Christmas in a Cup. That last item is a softball-size, hollow Mozart Ball that is placed in a festive red Mozart mug and filled with a hot-chocolate mix. Would Mozart have approved? Probably.

Mozart al fresco: In Austin, TX, at Mozart’s Coffee Roasters.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

These ventures hardly set precedent. The first person to realize, and capitalize, on Mozart’s commercial potential was the composer’s father, Leopold. As the actor Simon Callow wrote recently in The New York Review of Books (and it is impossible to impugn the credentials of the man who played Mozart in both the stage production and the BBC radio broadcast of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, and then appeared in a lesser role in the Oscar-winning film of the play):

“Their father immediately grasped the marketability of both Wolfgang and Maria Anna [the gifted elder sister] and whisked them off on tour in the fullest possible glare of publicity, much of it generated by Leopold. On May 17, 1764, just three months after Wolfgang’s eighth birthday, the readers of London’s The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser read an announcement of the forthcoming appearance of the greatest Prodigy that Europe or that even Human Nature has to boast of. ‘Everybody will be struck by Admiration to hear … a young boy of seven [sic] years of age play on the Harpsichord with such Dexterity and Perfection.’”

Acclaim has only grown, and when you hear the words “Mostly Mozart,” everyone, everywhere knows what you mean—a festival, most often in summer, devoted primarily to music by Mozart. Though other composers merit equal attention, we don’t find celebrations of “Heavenly Haydn” or “Bountiful Beethoven.” In fairness, we should acknowledge and applaud the Bard Music Festival; held on the Annandale-on-Hudson campus of Bard College every August since 1990, it has provided intense and comprehensive looks at many of the greatest composers, both in concerts and in scholarly publications.

Mozart and Frank Gehry’s architectural whorls: The Fisher Center—a performing arts hub at Bard College.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mostly Mozart, we might assume, was birthed at Lincoln Center, where an inaugural festival was held in 1966. But a Mozart Festival had been held in Würzburg, in Bavarian Franconia, since 1922. Vermont first staged a Mozart Festival in 1974, the same year that San Francisco’s Midsummer Mozart Festival debuted. OK Mozart, Oklahoma’s premiere performing arts festival, began in 1985 and was followed in 1987 by the Mozart Festival in Woodstock—that’s Woodstock, Illinois, an exurb of Chicago—and then in 1988 by San Diego’s Mainly Mozart. The newest member of the family arrived in 2000; it’s Spain’s Festival Mozart Coruña, in the Galician town of A Coruña.

Perhaps fittingly, the heart of Mozartian activities is Salzburg, where the composer was born in 1756, and where he lived intermittently for almost a decade. Yet there’s deep irony in the association. Though Mozart’s years in Salzburg were artistically rewarding, they were professionally unfulfilling and personally demeaning. The Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo, at whose pleasure he served, showed scant appreciation for his genius—still budding, but genius nonetheless. Despite his menial status, his music grew richer. With resentments on both sides but with power on only one, Mozart was eventually, unceremoniously, fired. Resentment lingered. We learn from Maynard Solomon in his essential biography Mozart: A Life, “When Mozart died, memorial gatherings and concerts were held in his honor in Vienna, Prague, Kassel, and Berlin, but not in Salzburg … and [b]etween 1792 and 1797, Mozart’s widow, Constanze Mozart, held benefit concerts featuring his music in Vienna, Prague, Graz, Linz, Dresden, Leipzig, and Berlin, but no such concert took place in Salzburg.”

Perhaps to make amends, Salzburg staged a Mozart Festival in 1921—130 years after the composer’s death; the Festival returns each January, around the date of Mozart’s birth. The celebration is an initiative of the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation, an organization devoted to all things Mozart. A shrine and destination, it sponsors research in all aspects of the composer’s life and legacy, it presents concerts throughout the season, and it collects, or tries to collect, everything written about the man and his music.

Founded in 1841 with bequests made by Mozart’s widow and by the two Mozart sons, Carl Thomas and Franz Xaver, the Foundation’s library—the Bibliotheca Mozartiana—houses, at last count, more than 35,000 books and articles.

It is safe to say that no book in its collection is quite like Mozart in Motion: His Work and His World in Pieces, written by the British poet Patrick Mackie.

The Mozart literature is vast, with foundational works that have supported more specialized studies. Looking across at my bookshelves, I count more than 50 books about the composer—a speck of the Bibliotheca’s holdings. There’s the catalog of Mozart’s works compiled by Ludwig von Köchel, first published in 1862; his listings, though occasionally amended, still set the chronological standard. There’s Maynard Solomon’s magisterial biography. There are solid and thoughtful studies by Daniel Heartz—Haydn, Mozart and the Viennese School, 1740–1780, and Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven, 1781–1802. And there’s The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, by Charles Rosen, who was an exceptional pianist and polymath. A brilliant synthesis of music history, analysis, and performance practice, it won the National Book Award on its publication. Mackie gratuitously dismisses both Rosen and his landmark study, and as we make our way through Mozart in Motion, we understand why.

Mackie’s book is best seen as a social history that places Mozart in the midst of changes wrought by the Enlightenment throughout Europe. The author has chosen 25 compositions, or usually movements from compositions, which he describes, discusses, and relates to the wider world.

Salzburg, faults and all, is the right place to start when dealing with Mozart. As Mackie writes, in a sentence stuffed like a sausage, “the little city presented (Mozart) with a manageable microcosm of Europe’s musical culture that sat at a nice point of geographical balance between the visions of that culture that Italy, Germany, and France often competitively pushed; its architecture mixed Italian with more northern pulls in some of the same ways as his music.”

Salzburg at the time was indeed culturally blessed, politically relevant, and economically prosperous. But that is not the city Mozart saw. The composer’s letters are the most primary of primary sources to get the measure of the man, and Solomon quotes from a letter sent from Salzburg: “I live in a country where music leads a struggling existence. As for the theater, we are in a bad way for lack of singers … I am amusing myself by writing chamber music and music for the church.” And as he later confided to a friend, “Salzburg is no place for my talent. In the first place, professional musicians there are not held in much consideration; and secondly, one hears nothing, there is no theater, no opera ….”

In a felicitous turn of phrase, Mackie writes that Mozart’s disappointment in Salzburg caused him to become “a sort of door-to-door salesman of his own brilliance,” and it was on the road that he won sizable success—in Milan (with the motet “Exsultate, jubilate”), in Paris (with the Symphony 31, the so-called “Paris”, in Prague (with Don Giovanni), and above all in Vienna. Sacred music he composed in Salzburg, and his violin concerti too, but his works that soar highest and probe deepest were fruits of his stay in Vienna. Among these are the peerless operas Le nozze di Figaro and Cosi fan tutte, his piano concerti from the 11th through the final 25th, and the final three symphonies.

Mozart in Motion offers some engrossing pages. Mackie’s chapter on the Victoire Jenamy: “Jeunehomme” Concerto, as it came to be known, is doubly fruitful. First, it corrects the widespread misconception that this Piano Concerto No 9 E flat major K 271 was composed by or for the “Young Man” of its nickname, when in fact it was composed for a certain Mlle. Jenamy, who met Mozart while passing through Salzburg.

And secondly, it relates that this Mlle. Jenamy was the daughter of Jean-Georges Noverre, the renowned choreographer who is said to have invented the ballet d’action forerunner of 19th-century narrative ballets—think Giselle or La Sylphide or Swan Lake—that today still hold the stage.

Mackie also offers a fine chapter concerning Mozart’s Requiem, which was commissioned anonymously months before the composer’s death. We remain unsure about its essentials. We now know that the project was an initiative undertaken by a Count Franz von Walsegg, who sought a memorial Mass to mark his wife’s recent passing. Mozart completed a small portion of the Requiem before his own death and otherwise left sketches. Ever since, scholarly disagreement has been ongoing about who completed the work. Was it Mozart’s pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr, or did Franz Josef Freystädtler and Joseph Eybler, two other Mozart students, also have a hand in the composition? Along with divergent opinions about authorship are divergent opinions about orchestration. A well-regarded article published years ago was headlined “Requiem But No Peace,” and Mackie is up to date on the continuing confusion.

With so many aspects of the Requiem still unclear, it perhaps is understandable that Mackie’s prose is a pileup of conditionals. All in one paragraph we get “Michael Puchberg … was very possibly the person”…; “It seems likely that …”; “Walsegg … a likely object …”; “Mozart’s imagination … may have been fired ….” A simple declarative sentence would have been a life raft in this sea of speculation.

Mackie, we must remember, is a poet whose verse has appeared in little magazines, including The Paris Review and The Poetry Review, where he has won admirers. His prose is another matter, and might present obstacles for a reader more interested in Mozart’s music—in the notes he actually put on paper—than in Mackie’s musings.

Taking note of this pungent prose, Simon Callow notes the author “remarks that ‘in art it is possible to be impatient and patient simultaneously; in fact great art relies on being so,’” and Callow continues that this is “one of many epigrammatic utterances in the book, usually paradoxical in form, which may or may not mean anything.” If Callow is often stumped, so am I.

In general, moments of insight are blurred by idiosyncratic writing and overshadowed by an insistent setting of Mozart and his works in the context of the Enlightenment. To make his point, Mackie marshals artists, both musical and not, so we find Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Giambattista Tiepolo, and William Blake meeting in a single sentence, as elsewhere we find a scrum of Nicola Porpora, Niccolo Jommelli, Johann Hasse, Leonardo Leo, and Antonio Caldera—all early-18th-century composers mostly associated with Neapolitan opera and its ornamental excesses.

Some further observations: Concerning the shape and substance of what he calls “Mozart’s finest concertos and symphonies” without naming these works specifically, Mackie writes that they “can reveal themselves as brilliantly flexible narratives of errancy and homecoming, [and] can amount indeed to existential allegories of the fates of psyches and societies pitched into change.”

The notion of “errancy and homecoming,” of departure and return, might fairly be applied not only to Mozart’s “finest concertos and symphonies,” but to virtually all of his works, as well as to works of his contemporaries. Departure and return is the fundamental premise of the sonata form, which was the reigning structural template of the Classical era—most basically, music moves from the tonic, or basic, key to the dominant key and back to the tonic—and it governs the music of Mozart and his time. To apply this principle to “psyches and societies”—and here Mackie surely has in mind Mozart, most of whose 35 years were spent in transit—seems a stretch.

Misguided, too, is the belief that instrumentalists could not meet the challenges Mozart posed. This notion is expressed most clearly, and most unfortunately, in his thoughts about Mozart’s writing for horn.

Composers have always had their favored instrumentalists, and Mozart’s favorite hornist was Ignaz Leutgeb, for whom the composer wrote his horn concerti and the quintet for horn and strings.

Mackie speculates that “Leutgeb was probably not a particularly educated or cultivated man … ,” offering no evidence to support his assertion other than that Leutgeb and Mozart shared a warm and joking friendship. “But the bigger point,” the author continues, “is that a virtuoso horn player, at this juncture in the history of music and that of the instrument, was an inherently funny thing to be. It meant being a contradiction in motion, someone pledged to mastering especially stubborn difficulties without ever reaching the slick showmanship that is meant to be the virtuoso’s payoff.

“The horn had not yet started to use valves to give more control to the flow of air through its tubes, so its range of notes was very limited, and even these were hard to play with any great expressiveness or technical panache.”

Is this true? Was he there?

These are stunning assumptions that display a deep lack of knowledge. Composers have always composed for musicians who could play their works. In an earlier day, for instance, Vivaldi wrote multiple concerti for two horns and strings, and we have no reason to believe that these pieces, like Vivaldi’s demanding concerti for violin or cello or flute, were not played as written. Handel, too, composed for the virtuoso horn, in the popular Water Music and more notably in the opera Giulio Cesare. Toward the end of the opening act, the solo horn teams with Julius Caesar in a showstopper of an aria, “Va tacito.” There’s no reason to think that musicians of an earlier day did not meet the challenges asked of them.

In my mind, however, the most unforgivable shortcoming of Mozart in Motion is the total lack of musical examples. Mackie’s flowery, self-conscious prose is a poor substitute for an informed appreciation of Mozart’s music.

Charles Rosen offers an alternative approach. The Classical Style is rich in musical examples, and they are explained with a clarity that instructs and informs both amateur and professional. This approach, and Rosen’s mastery of the material, engenders a high degree of confidence.

Between Rosen’s fact and Mackie’s fancy, there is another path. Peter Shaffer explores it in his play Amadeus, which, though fictional, is not without truths of its own. Though no longer with us, Shaffer the man had keen musical insights, and Shaffer the playwright had the skill to give authentic voice to his feelings.

Perhaps the play’s most telling moment occurs when Antonio Salieri, the composer portrayed as Mozart’s archrival and played in the film by F. Murray Abraham, for the first time hears a wind band playing a movement from Mozart’s so-called Gran Partita, KV 361 (370a), an adagio of modest gait:

“On the page,” recalls a stunned Salieri, “it looked nothing. The beginning simple, almost comic. Just a pulse—bassoons and basset horns—like a rusty squeezebox. And then suddenly, high above it, an oboe, a single note, hanging there unwavering, until a clarinet took it over and sweetened it into a phrase of such delight! This was no composition by a performing monkey! This was a music I’d never heard. Filled with such longing, such unfulfillable longing. It seemed to me that I was hearing the voice of God.”

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles has also written about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: