ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

You’ve Never Heard of Soundies?

These three-minute nostalgia-laden music and dance blasts, played on jukeboxes with screens in the 1940s, rate as online must-sees today

By George Gelles

The Nicholas Brothers ‘Jumping Jive’

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Oct. 13, 2022

With a plethora of popular culture easily accessible online, there’s one corner of the performing arts that thus far has been largely ignored: Soundies—an American phenomenon that was ubiquitous through much of the 1940s.

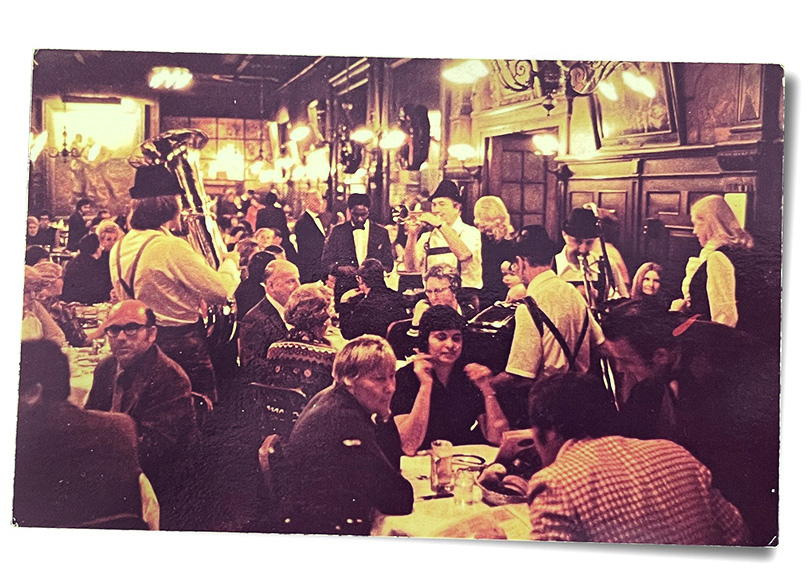

Should the term be new to you, as until recently it was to me, a Soundie is a performance, usually of music or dance, drawn from the gamut of popular styles, viewed on a console called a Panoram. Imagine a jukebox with a screen measuring a generous 17 x 22 inches. And the technology was user-friendly: you fed the Panoram a dime, and one of a pre-selected set of Soundies played for your enjoyment.

As Jan-Christopher Horak, the former director of UCLA’s Film and Television Archive, tells us in his essential blog, Archival Spaces: Memory, Images, History, “While the 3,000 to 4,500 Panoram movie jukebox machines were manufactured by the Mills Novelty Company of Chicago, the Soundies films were produced by affiliated subsidiaries, like RCM Productions in Hollywood and Minoco Production in New York …. Placed in bars, restaurants, defense plant lunch rooms, bus and train stations, and other public spaces, [the system] forced producers to turn out Soundies quickly and extremely cheaply. Nevertheless, the whole financial structure of the operation remained shaky at best, until finally it collapsed in the immediate post-World War II years.” Though not strictly Soundies, performances filmed for video jukeboxes were made before 1940 and into the ’50s. They perhaps can be thought of as forerunners of MTVs.

In Soundies and the Changing Image of Black Americans on Screen: One Dime at a Time, the film historian and critic Susan Delson notes that “African-Americans participated in over 300 of the ca. 1,880 Soundies produced between 1940 and 1946, making them the first mass entertainment media in which they were not marginalized or relegated to racist stereotyping.” This in general is true; but as we shall see there were lamentable exceptions.

Soundies include it all: old-fashioned vaudeville routines, then-cutting edge jazz artists, nightclub routines, and kitsch. As seen on the YouTube collection packaged by Films Around the World, an enterprise founded in 1985 that owns and distributes a vast array of earlier media products (television programs, radio shows, feature films, as well as Soundies), many Soundies performers would not be out of place among those oddball wannabes hoping to audition for talent agent Broadway Danny Rose, in Woody Allen’s nostalgically touching film of the same name.

There, we had a ventriloquist, a talking bird, a glass harpist, a stuttering comedian, balloon sculptors, blind xylophonists, piano-playing birds. Here we have cowboy campfires, Hawaii hula idylls, gay caballeros, sheiks and their harems, cabaret crooners and big band swing, sock hops, a fan dance, a balloon dance, musical glasses (a/k/a the glass harp), a formidable all-women orchestra—the International Sweethearts of Rhythm—and a lamentable all-woman orchestra, Dave Schooler and his 21 Swinghearts. As Professor Horak suggests, talent was not a big item on the budget for Soundies.

And yet there are performances to treasure. These most often were rendered by Black artists, whose visibility in mainstream White movies was limited to cameo turns or more often to stereotypical and demeaning roles. But Black performers were creating their own subculture, and Soundies gave these brilliant musicians and dancers the wider audience they deserved.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Let’s start with the irrepressible “Martha’s Boogie,” from 1951. Wichita-born and Chicago-bred, Martha Davis fell under the spell of the irrepressible Fats Waller. Oscar Levant, the pianist and professional iconoclast, called him “the Black Horowitz,” referring to the classical keyboard superstar Vladimir Horowitz. The same compliment might be paid to Davis. Like Waller, she possessed an imposing presence, a flawless technique, a magnetism that never quits. John S. Wilson, who enjoyed a four-decade career as jazz critic for The New York Times, wrote, “as a pianist, Miss Davis is somewhere in the neighborhood of fantastic. She has tremendous dexterity, a remarkable sense of rhythm and a powerful and accurate left hand, which she uses to make some well-known boogie-woogie themes seem fresh and gay.”

She married bass player Calvin Ponder, seen in the “Martha’s Boogie” Soundie from 1946. Individually and together, they were eminent, if to most people unknown. They developed a music-and-comedy act, “Martha Davis & Spouse”, that was popular in the post-Soundies late-1940s and ’50s, both on tour and in New York, where they were marquee performers at the Blue Angel—one of the city’s premiere nightclubs.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Another superstar pianist—even less known—is Lynn Albritton. Jessica Salmonson, the eccentric, eclectic, yet discerning blogger whose handle is Paghat the Ratgirl, writes that “as a club performer, Lynn was one of the boogie-woogie virtuosos of Harlem,” and her Soundie of “Dispossessed Blues” (1943) is sublime.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

“Lynn Albritton,” Salmonson continues, “begins playing her upright piano even before she seats herself. She’s playing “Dispossessed Blues” in her Sunday best, a flower in her hair, smiling and showing her gorgeous profile as though knowing perfectly well what a gosh darned beautiful woman she is.

“This is a direct prequel of (the Soundie) “Black Party Revels,” as it shows how Lynn’s piano got outside in the street for the party later that night. She’s been evicted!”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Dandridge had it all—she was a singer, dancer, and actress, both on stage and in films.

Perhaps the first Black actress to have been embraced by Hollywood, she was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for her performance in Carmen Jones (1954) and nominated again for a Golden Globe for Porgy and Bess (1959).

Her 1942 performance of “Zoot Suit,” with Paul White, is glorious.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Dandridge at twenty already shines like a star. Without White’s overacting, she convinces us, without trying, that she was born to perform. Her every aspect—her singing, her presentation—is natural, and the camera loves her, as do we.

Another sensational Soundie is Dandridge’s performance of “Cow-Cow Boogie,” a blues song composed for the Abbott and Costello film Ride ’Em Cowboy (1942):

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Though cut from the movie, the song has been much recorded; the Ink Spots with Ella Fitzgerald, the Mills Brothers, Mel Torme, and others have their versions.

But none have the playful, knowing innocence of Dandridge herself. Her performance asks to be compared with another Wild West saloon showpiece, Marlene Dietrich’s bawdy rendition of “The Boys in the Backroom” in Destry Rides Again. At 38, Dietrich flaunts her sex. At 19, Dandridge quietly sizzles.

Dandridge, however, remains a prime and regrettable example of a phenomenon the critic Susan Delson rightly deplores: becoming “marginalized or relegated to racist stereotyping.”

Hoagy Carmichael, one of the most celebrated songsmiths on Tin Pan Alley (the fictitious home of the American songbook), collaborated with lyricist Johnny Mercer on the mega-hit “Lazybones,” from 1933. In 1941, Carmichael made a Soundie of the song, with Dandridge receiving star billing.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Yet nowhere in the song does Dandridge dance or sing. Rather, she plays the foil for a hapless Black waiter, the Lazybones of the title. As he balances on his head a tray with coffee service, Carmichael sings from the keyboard, berating the waiter—“sleeping in the sun all day, you’ll never make a dime that way.” All the while, he is flanked by attractive White women who show their amusement at his bigotry. More crass racial stereotyping would be hard to imagine.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The 1940s were the epoch of female big bands, or “all-girl” bands or orchestras, as they were called at the time. No doubt there was an abundance of gifted woman musicians, but it took the Second World War to bring them to the fore. With men, both musicians and non-musicians, fighting abroad, the vacuum created by their absence was filled by women.

Among the most prominent of these groups were the Darlings of Rhythm, Frances Carroll and Her Coquettes, Ina Ray Hutton and her Melodears, and Ada Leonard and Her All-American Girl Orchestra. Some groups were all-Black, some were all-White, and some were racially integrated. Most were highly accomplished, but none was as accomplished as the International Sweethearts of Rhythm.

The International Sweethearts was the country’s first integrated all-women band. The original members, age 14-19, had met at the Piney Woods Country Life School, near Jackson, Mississippi—a school for indigent and often orphaned Black children. The band got its “international” flavor from the inclusion of diverse nationalities: Asian, Caucasian, Latin, Black, Indian.

No group would swing harder. A commentator observed that “though they don’t get much recognition and attention like Duke Ellington and Count Basie and never were inducted into the Jazz or Swing or Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, these women were just as good as the men and could really swing hot jazz, they were talented and—plus—beautiful … and here’s the proof. Anna Mae Winburn, the bandleader, led the band with beauty, elegance, style, and glamour.”

For a typically polished performance, every bit the equal of more storied bands, listen to “She’s Crazy With the Heat,” from 1946.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Equally eminent in their field were the Delta Rhythm Boys, formed in 1934 at Langston University, the only historically Black college in Oklahoma. The group enjoyed an exceptionally long career of 53 years.

“Take the A Train,” Billy Strayhorn’s 1939 classic, became the signature tune of Duke Ellington, but it received early exposure in this 1942 Soundie from the Delta Rhythm Boys.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

For all the suave musicianship of Ellington and his crew, it’s hard to imagine a more authentic and genuine performance than that offered here. As in so many of the group’s great performances, the tone is set by the affable personality and resonant warm baritone of Lee Gaines—the word “debonair” must have been coined to describe him. Gaines wrote the lyrics for this recording of “A Train,” lyrics Ellington would later change.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The lyrics Gaines wrote for “Take the A Train” make prominent mention of Sugar Hill—that’s where the A Train takes you. And Sugar Hill is often mentioned in other Soundies of the time: in the “Sugar Hill Masquerade” (1942) featuring Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

in the “Chicken Shack Shuffle (Up on Sugar Hill)” (1943), with the exuberant jazz dancer and singer Mabel Lee,

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

and in “Walking With My Sugar on Sugar Hill” (1936), featuring the extraordinary Babe Wallace, whose easy and casual way with words brings Fred Astaire, when singing, to mind, though Wallace is a far more polished crooner.

. . . . . . .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eaMuIrcXHZ0

. . . . . . .

Now designated a National Historical District, Sugar Hill is a section of Harlem whose renown perhaps has faded. Learning of this neighborhood was new to this native New Yorker, and I suspect I’m not alone.

It’s a rectangle between 145th and 155th Street, and between Amsterdam Avenue to the West and Edgecombe Avenue to the East. It’s a bit to the South and a bit to the East of Washington Heights, another largely homogeneous enclave that was brought into focus by the prodigious Lin-Manuel Miranda, in his stage musical and then his film “In the Heights.”

In the 1920s, Sugar Hill began attracting some of Harlem’s intellectual and cultural elite. The counterpoint to Harlem’s vigorous retail and entertainment hub on 125th Street—the Apollo Theater was perhaps the Street’s biggest draw—Sugar Hill, a mile to the north, became home to some of the most eminent leaders in their fields: to future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, to W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black PhD. from Harvard who was a scholar and advocate for Black causes, a force at the time like no other; to Roy Wilkins, civil rights activist who spent more than four decades increasing the power and prestige of the NAACP; to Duke Ellington and Willie Mays.

In 1944, The New Republic published an essay by Langston Hughes, the novelist, playwright, and poet, who spent his life crusading for equal recognition for Blacks. He had this to say about the true nature of Sugar Hill: “Don’t take it for granted that all Harlem is a slum. It isn’t… There are big apartment houses up on the hill, Sugar Hill… nice high-rent-houses with elevators and doormen … where colored families send their babies to private kindergartens and their youngsters to Ethical Cultural School.”

To dream of a better life or simply sample an upper-class neighborhood, as downtown folk might stroll up Fifth Avenue, Madison or Park on the Upper East Side, Sugar Hill was an aspirational destination.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

If the “A Train’ video is literal in its subway car setting, “Gimme Some Skin My Friend” looks far into the future.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

In this 1940 Soundie, the cinematographer—artist unknown—anchors the film with shots of the quartet, their shadows being as important as the singers themselves, and cuts multiple times to hands giving skin, to images whose angles are askew, to individual close-ups that you’d find in film noir, and vignettes that you’d find in Expressionist film.

Lastly, you must watch the “Rigoletto Blues,” a 1941 Soundie send-up of the Act 3 quartet from the Verdi opera. Costumed and bewigged, the Delta Rhythm Boys are marvelous hams and, of course, they sing beautifully. In the canon of Soundies—in the canon of opera—their “Rigoletto” is surely unique.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Black dance on Soundies is generally less distinguished than Black music. But typical is a 1944 performance by Meritta Moore and Dancers—“Dance Revels.” It’s nightclub swing, proficient but generic.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

The same can be said of “Chatter (I Got Rhythm)” from 1943, featuring the male duo Cook & Brown and the three-women combo known as the Sepia Steppers.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Keep an eye out, however, for the woman dancer on the right; she’s Alice Barker, perhaps the most admired female dancer of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s and ’40s—a regular at the Cotton Club and the Zanzibar Club, and a member of the legendary dance group, the Zanzibeauts.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Though their artistry and their popularity were not captured on Soundies per se, Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers bequeathed us filmed performances that remain unequaled. And while each was a tap virtuoso, they couldn’t have been more different, occupying opposite ends of the artistic spectrum.

Bill Robinson took the basics of tap and refined them to their essence. His finest works have an irreducible purity. Jazz historian Marshall Stearns wrote that “Robinson’s contribution to tap dance is exact and specific. He brought it up on its toes, dancing upright and swinging,” adding a “hitherto-unknown lightness and presence.” None of his work surpasses “Stair Dance,’ and this 1932 performance, an excerpt from the feature film Harlem is Heaven, is unmatched in concept and execution.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

In a field where competition is often more conspicuous than consensus, there is general agreement that the Nicholas Brothers—Fayard and his younger sib Harold—were, and remain, in a class by themselves. Few would argue with this assessment by critic Mindy Aloff: “it wasn’t the acrobatics in themselves that made the Nicholas Brothers the Nicholas Brothers. It was the overall beauty and musicality of the entire dance. Their achievement was in the how—the way Fayard would deploy his hands, as graceful as Fred Astaire’s; the way Harold would make every silhouette super clear; the genial, noncompetitive way each brother would cede the floor to the other for a solo, passing the dance like a baton, in musical time.

“When Astaire pronounced the Nicholas Brothers’ “Jumping Jive” number—unrehearsed and achieved on the first take—in the movie Stormy Weather (1943) to be the greatest dancing he had ever seen on film, he was not commending the acrobatics alone, but rather the way the brothers erupted organically out of their tap steps, like a series of overlapping geysers that, simply to look at, project an observer into a stratosphere of elation.” (With Cab Calloway for the first few seconds.)

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Over time, Soundies’ content would evolve. Rather than offering a little of everything, as at their onset, they became more focused. In Volume 11 of the YouTube collection, the first eight of 16 numbers are burlesque bump and grind. Volume 12 features Western-themed lonesome cowboys, while lovelorn ballads are grouped in Volume 13. Volume 15 offers six songs from Hawaii, and in Volume 18, the last of the collection, six of the 18 numbers feature Black performers.

As for jazz, which featured prominently and gave the Soundies real distinction, that too would change. Frank Tirro, pioneering jazz scholar and one-time dean of the Yale School of Music, has observed that “bebop musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Kenny Clarke were trying to change jazz from dance music to a chamber music art form,” and their success changed the nature of Soundies.

Nonetheless, exploring this treasure trove offers endless enjoyment. And by sharing the song and dance of the Black performers, we honor these remarkable artists for their enrichment of our culture.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles also wrote about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: