ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Edible Memories: Lunch at Lüchow’s with Lauritz Melchior

1965: Dining with an outsize opera tenor at downtown New York’s bastion of German cuisine

By Ian Strasfogel

Location, location: Luchow’s in the 1930s, decades before it became “less restaurant than mausoleum.” Photo by Berenice Abbot, from the NYPL Digital Collections.

February 5, 2024

February 5, 2024

Sometime during the spring of 1965, my mother announced that Lauritz Melchior wanted to take me to lunch at that mammoth, well-established German restaurant on East 14th Street, near Union Square, which I knew only by name.

“Mom, he hardly knows me.”

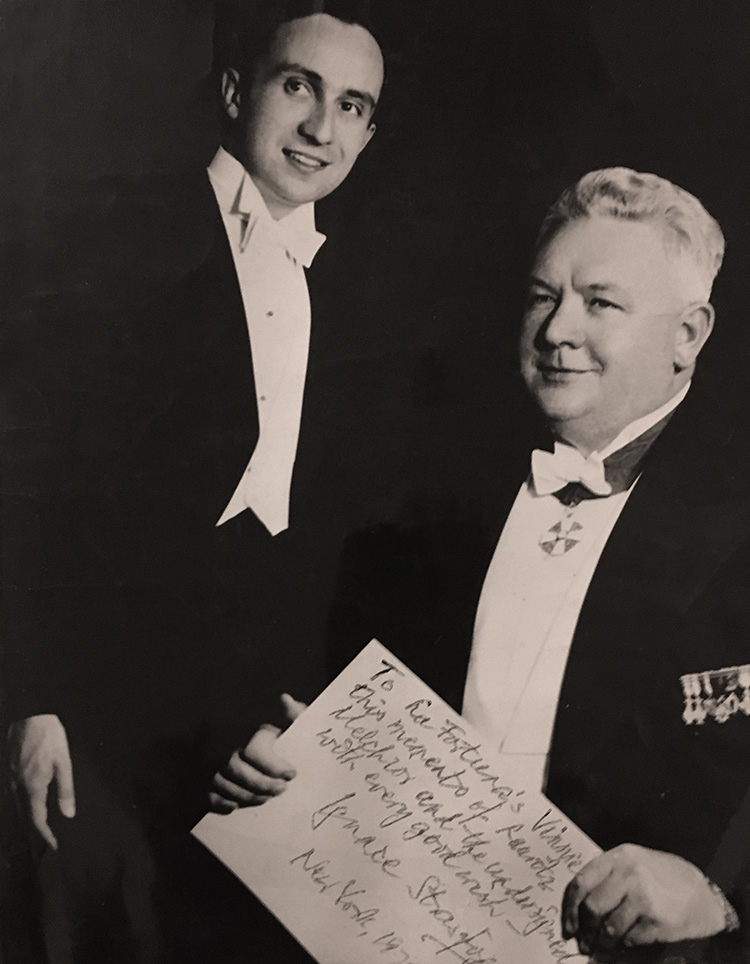

“Darling, he held you in his arms when you were a baby.” This was probably true. My parents had always been close to the tenor—a great star at the Metropolitan Opera during the 1940s and ’50s. My father had served as his accompanist; they toured together and made numerous recordings.

“But why Lüchow’s?” I asked. “It’s totally over.”

“It’s always been Lauritz’s favorite restaurant, and he really needs cheering up. First, Mr. Bing [Rudolf Bing, the general manager] wouldn’t invite him back to the Met. Then Kleinchen, Lauritz’s beloved wife and manager, died, and he quickly married a much younger woman who only wanted his money. That didn’t last long, thank goodness. We had him over for dinner the other day, and he was totally unlike himself—morose and silent. He needs a breath of fresh air.”

As a 25-year-old, I hardly felt up to the task, but I called Lauritz and arranged our little lunch.

I met him outside Lüchow’s on a blustery April day. Even at 75, he was a towering figure—an aging Viking (yes, from Denmark) with ruddy cheeks and a booming speaking voice. I felt uneasy about dining with a man I barely knew, but Lauritz seemed genuinely happy to see me. He nearly smothered me with his welcoming embrace.

In full regalia: The author’s father, Ignace Strasfogel, left, with the tenor Lauritz Melchior, circa 1943. Among the medals Melchior is shown wearing is Denmark’s rarely awarded Ingenio et Arti, for achievements in the arts and sciences.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

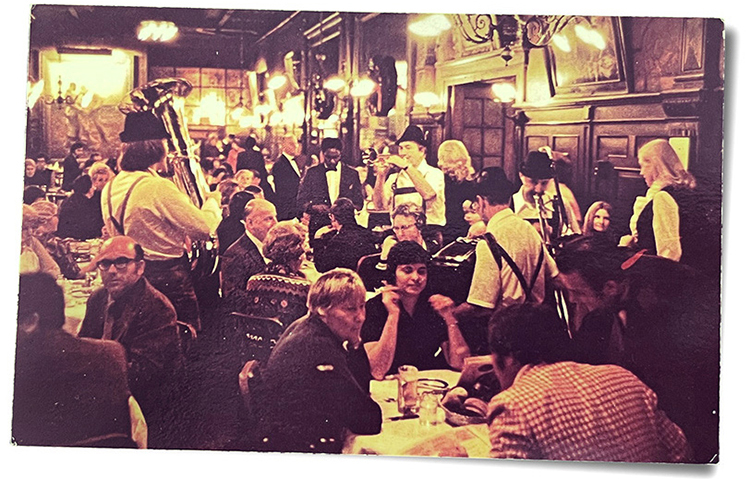

I held the door open for him as we entered a vast wood-paneled space dotted with oversized kitsch paintings and elaborate wrought iron light fixtures. The room felt like a mash-up of dusty remnants from Diamond Jim Brady’s New York. (Diamond Jim was one of the most loyal customers of August Lüchow, the restaurant’s founder.) To me, the whole place, built in 1882, with its neoclassical frieze and six-bay façade, felt gutted—less restaurant than mausoleum—though in the late 19th century it had been the dining place of choice, favored by the local thriving German community that later decamped for the Upper East Side. Of the 40 or 50 tables scattered around the room—tables that had come to be occupied by such luminaries as John Barrymore, O. Henry, Theodore Dreiser, and Thomas Wolfe—only five or six were occupied.

As a young waiter led us to our table, the room’s glumness seemed to weigh on Lauritz. “Where are all the people?” he asked. “Every time I came here after performances, the place was crowded to the ceiling. It was lively and convenient, just a short ride from the Metropolitan. Even after long shows like Tristan or Parsifal, they always kept open for me.”

I was careful not to mention that the old Met on 39th Street, the scene of Lauritz’s greatest triumphs, his heroic Siegfried, his passionate Tristan, was about to be demolished and replaced by a new theater at Lincoln Center. Why point out that time had emphatically moved on?

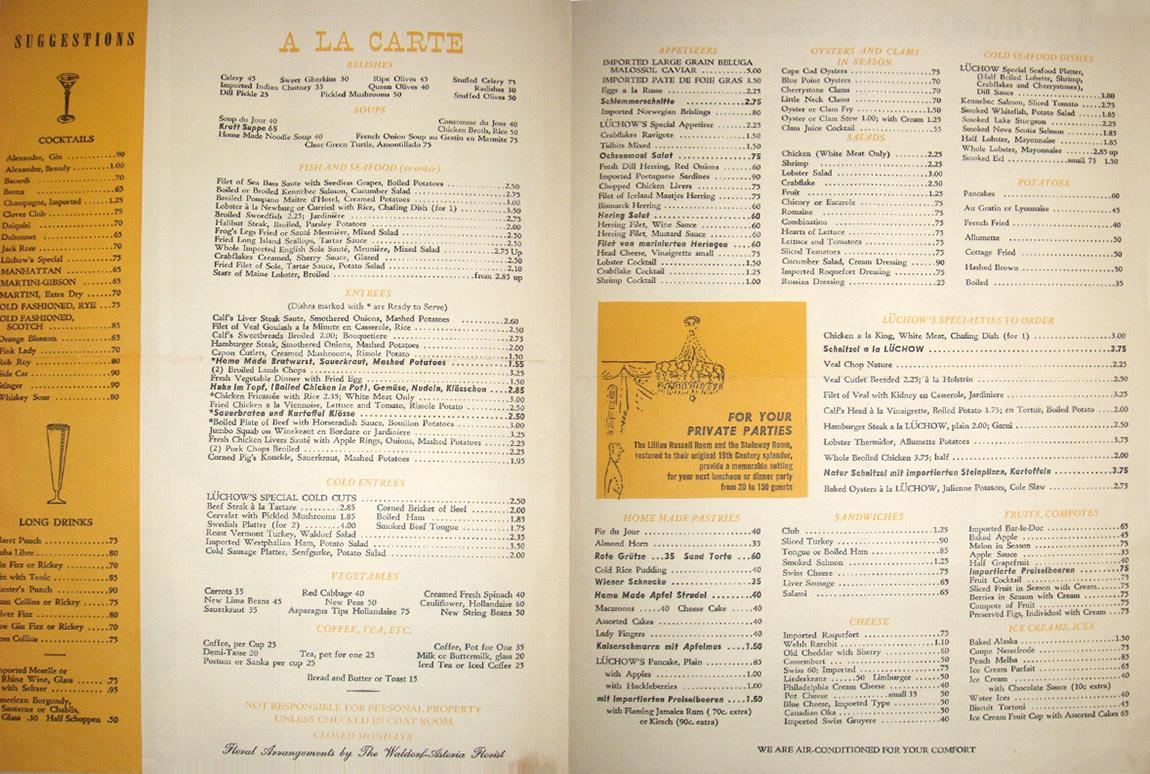

As we scanned the long menu, Lauritz’s face brightened. “Ach, they still have the sauerbraten. That’s my favorite. You should order it too.”

“Honestly, it’s a bit heavy for lunchtime. I think I’ll just go with a sandwich.”

“A sandwich? You’re too thin.” He smiled and poked me in the ribs. “You need to get flesh on those bones.” (At 350 pounds, Lauritz had flesh enough for both of us.)

Pre-Lean Cuisine: As late as the 1960s, Luchow’s menu continued to feature such items as Sauerbraten and Calf’s Head à la Vinaigrette.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

While waiting for our meal, he asked me about my career. I’d just become an assistant at the New York City Opera and soon found myself gushing about all the marvelous young singers there—soon-to-be-rising stars like Beverly Sills, Norman Treigle, and Judith Raskin. Their names, however, meant nothing to Lauritz, probably because they weren’t famous yet. He had always circulated in the operatic stratosphere with the most famous of the famous—conductors like Toscanini and Furtwängler and singers like Flagstad and Lotte Lehmann.

It gradually became clear that we were seriously mismatched. I’d recently graduated from Harvard and saw myself as a budding intellectual whose gods were Brecht and Kafka. And even though he sang opera, Lauritz was very much a pop culture guy. He’d gone out to Hollywood in the 1940s to make a cluster of B pictures with lesser lights like Kathryn Grayson, Jane Powell, and Van Johnson. He didn’t have any interest in The Trial or The Sun Also Rises, and I hadn’t seen his movies, which my friends found pretty lame.

During lulls in our conversation, and there were plenty, we consoled ourselves with Luchow’s bland cuisine. It didn’t help much, but at least we had something to do.

After we’d finished, Lauritz summoned the waiter. “Tell me, young man, is by any chance Ernst Seute here today?”

“Who?”

“Ernst Seute.”

“Sorry, I never met anybody named Ernst. Are you sure he works here?”

“He’s the face of Lüchow’s, the life of the party. He was just a boy when he was hired by old man Lüchow himself. He waited on me the night of my debut at the Met. I had pig knuckles, because I knew it was Caruso’s favorite dish.” The waiter did his best to look interested as Lauritz strolled down memory lane. “I last saw old Ernst in the 1950s when I came to New York for The Ed Sullivan Show. He greeted me at the front door, just like always. ‘Can I get you a nice beer, Mr. Melchior?’ He knew I loved my beer.”

“Would you like to look at our beer list?” asked the waiter.

“No, thanks, not today, but I will have dessert. How about some pfannkuchen?”

“Sorry, what?”

Lauritz could barely conceal his irritation. “Pfannkuchen, apple pancake. It’s your very best dish—this wonderful thick German pancake, with apples and sugar and cinnamon. Surely you still have it.”

“Sorry, it’s not on the menu. At least, not since I got here.”

Lauritz looked stricken.

“But we do have some delicious strawberry shortcake, or chocolate seven-layer cake.”

Lauritz brightened. “I’ll take both. With two forks, of course, to share with my starving young friend here.”

When the desserts arrived, I did my best to stave off Lauritz’s persistent attempts to stuff me full of sugar.

As he demolished both desserts, our conversation stumbled along erratically. Despite the best will on both his part and mine, we didn’t have much chemistry. I’d failed in my mission to boost his spirits. He still seemed gloomy and at sea. A kid had been sent in to do a man’s job.

We finished our meal in an amiable but low-key way, vaguely disappointed, but not sure exactly about what. Obviously, Lüchow’s was no longer the pleasure house Lauritz remembered, the thriving eatery of his glory days at the Met, where he’d picked up the tab after a long night of dining and drinking with colleagues and ardent admirers. In point of fact, the establishment would soon be sold and demolished, giving way to a prison-like dorm for NYU.

As Lauritz paid the bill, I saw out of the corner of my eye a little girl around ten or eleven, her thin blonde hair neatly gathered into two tidy braids. With a timid smile on her lips, clutching a ballpoint pen and spiral-bound notepad close to her thin young chest, she cautiously approached Lauritz and addressed him in a frail, tentative voice. “Excuse me, Mister Melchior, could you please give me your autograph?”

Fifteen years after he’d abandoned New York for Hollywood, Lauritz still had a fan club. He bubbled over with animal delight as he took the little girl’s pen and embraced his celebrity.

Lauritz had finally cheered up.

Ian Strasfogel is an author, opera director, and impresario who has staged over a hundred productions of opera and music theater in European and American opera houses and music festivals. His comic novel, Operaland, and his biography of his father, Ignace Strasfogel: The Rediscovery of a Musical Wunderkind, were both published in 2021.

Other articles by Ian Strasfogel: