ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget … Maria Callas as Tosca, 1965

The fabled diva compelled and galvanized the public as Puccini’s tragic heroine at the Metropolitan Opera

By Ian Strasfogel

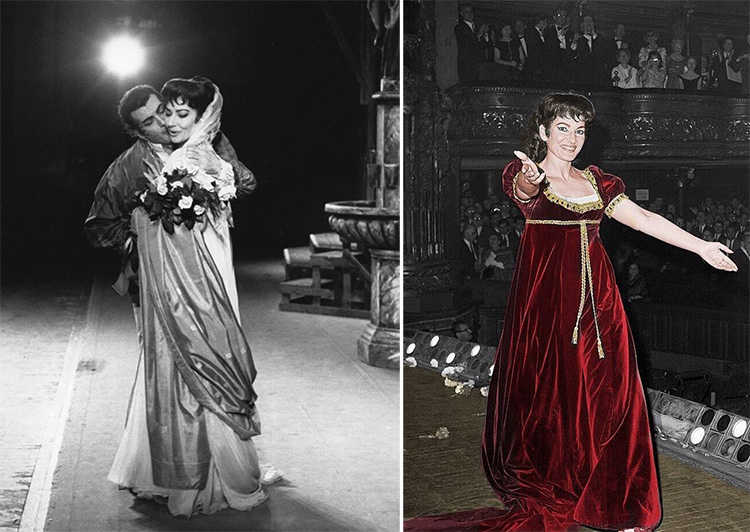

Callas exasperates and enchants tenor Franco Corelli in Tosca’s first act love duet. Callas exalts with her public at the end of Tosca—Metropolitan Opera, 1965.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

November 15, 2023

November 15, 2023

I’m one of the lucky few who actually saw Maria Callas perform—a Tosca at the Metropolitan Opera in 1965, her next-to-last performance there—and I’ve never forgotten it. She transformed the theater into a sacred space.

The old Met that evening was jammed with opera fanatics. Anticipation ran absurdly high. Callas was more than just the most famous opera singer of the day; she was a worldwide celebrity. So great was our eagerness to hear her that when she sang her first offstage lines, we let out a collective gasp. The great diva was actually going to sing! Childish and no doubt ridiculous, but it had been seven long years since her last performance at the Met. We had missed her so much, had hoped so fervently for her return, that the first hint of her incisive, almost acidic voice hit us like a hammer stroke.

When she made her entrance, we exploded in tumultuous applause. Despite all our cheering, despite the utter pandemonium, she did something quite remarkable, which I, just out of college and already launched on my career as an opera stage director, especially appreciated. She did nothing.

She pretended we weren’t there. She wasn’t the world-famous Maria Callas, she was Floria Tosca, Puccini’s impulsive diva, and she was red-hot furious with her thoughtless lover Cavaradossi, who had kept her waiting outside on the street. Despite our wild shouts of adoration, she faced him angrily and never once strayed from the scene. By the time the music resumed, her charisma, her supercharged physicality, had imprinted on us exactly who her character was—an impulsive, passionate woman hopelessly in love with an ardent revolutionary. The scene that followed, all too often presented as a tuneful but bland Italian love duet, surged with erotic urgency. The connection between Tosca and her lover was palpable. I’ve never seen the tenor Franco Corelli so alive onstage, so compellingly engaged. La Callas had clearly inspired him.

Strangely enough, it’s hard for me, all these decades later, to pinpoint how well Callas actually sang. She had rarely performed in the 1960s, and there were reports from Europe of significant vocal deterioration. Aside from a botched high C in her third-act narrative, her voice sounded rich and unforced and commanded our full attention. But immaculate vocalism wasn’t the point. All that mattered to her or to us was expressiveness—musical and dramatic truth. She brought us face to face with Tosca’s suffering and forced us to contend with it. We weren’t watching an opera that evening; we were witnessing Greek tragedy.

Tosca gripped by anguish as she lays her eyes on the knife. Photo by Louis Mélançon/Metropolitan Opera.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The crux of the opera comes at the end of the second act, when Baron Scarpia, the repulsive chief of police, agrees to spare Cavaradossi’s life if Tosca spends the night with him. She has no alternative and looks on grimly as Scarpia writes a safe-conduct pass for her lover. What follows is one of opera’s most famous moments. Tosca sees a knife on the small dining table that Scarpia has laid out and realizes she must kill him. Over the many decades since Tosca’s premiere, singers and directors have contrived various ways to portray this crucial event.

Some prima donnas have nervously spilled a glass of wine, and as they mop it up they stumble across the obliging fruit knife. Others have leaned back against the dinner table in despair—and in doing so, accidentally placed a hand on the weapon. All such contrivances produce an effective little jolt, but they’re basically just tricks.

Callas did something bolder and technically far more difficult. She simply saw the knife. She just concentrated on it, and as she did so, her body taut with animal tension, everyone in the vast auditorium gasped. How could such a familiar moment have felt so fresh to us, so totally, horribly alive? I’m sure it was because Callas showed us what the moment meant to her character. She gave us the subtext—the story behind the story. Her Tosca realized at that split second that she would have to kill her tormentor. The prospect of murdering him shamed her, sickened her, terrified her. And horrified us, as well.

The agony continues. Callas singing Tosca’s famous second act aria, Vissi d’arte. (Link to the NYT’s clip.)

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The second act ends with a long mime after Tosca kills Scarpia. She is ready to rush off to her lover when she remembers that she needs the safe-conduct pass. She searches frantically through Scarpia’s cluttered desk, but it isn’t there. Increasingly desperate, she races around the room, hunting for the document. Suddenly, horribly, she realizes that it is still clutched in the dead man’s hand. She pries it free, collects her things, and is about to leave when she has a change of heart. She can’t leave the police chief’s corpse unacknowledged. With solemn ceremony, she places candles at Scarpia’s outstretched arms and a crucifix on his chest. Only then can she rush out the door to save her lover.

For me, this three-minute mime, when Callas didn’t sing a single note, was the high point of the evening. She performed the actions exactly as specified in the score, but they felt completely new. Her depiction of Tosca’s horror at having killed Scarpia was so vivid that I was afraid she was going to throw up. It was acting, of course, but so close to the bone, so extremely, explicitly real, that I was completely lost in the moment, sucked into it by her volcanic talent. This in-your-face actuality, this larger-than-life reality, was the unique genius of Maria Callas. No one has rivaled it before or since.

When I said at the beginning that she transformed the Metropolitan Opera House into a sacred space, I meant it quite literally. On that memorable evening in 1965, she showed us the true cost of Tosca’s desperate deed—the living hell she experienced. Aristotle proposed that the purpose of tragedy was to confront a hero with an action so grave and so profound that his (or her) reaction to it would unleash in the public the twin emotions of pity and awe. I pitied Maria Callas and her terrified, doomed Tosca. And I was in awe of her.

Ian Strasfogel is an author, opera director, and impresario who has staged over a hundred productions of opera and music theater in European and American opera houses and music festivals. His comic novel, Operaland, and his biography of his father, Ignace Strasfogel: The Rediscovery of a Musical Wunderkind, were both published in 2021.