ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Baton-Wielding, Arm-Waving Women

Despite daunting odds, a handful of high-energy, vastly talented, rule-breaking ladies are shaking up the male-dominated American orchestra-conducting world

By George Gelles

Arm waver: Marin Alsop, until recently the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, here leading the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra, 2017. Photo: Gilberto Marques/A2img.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Covid’s devastation in the cultural realm has been severe—not least when it comes to musical performances. It’s little wonder, then, the long-sought emergence of women conductors heading American orchestras has gone largely unnoticed.

The favorite trope is that woman conductors don’t exist—or if they do, they shouldn’t. A firestorm of sorts was ignited several years ago when the Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko spoke what others might think. Orchestra musicians “react better when they have a man in front of them,” he proposed, adding: “A cute girl on the podium means that musicians think about other things.” Long associated with London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, he also serves as conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain—a preposterous appointment, given his ignorant comments while working with children. Subsequently, Petrenko (who is not related to Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic) issued a potted, pro forma apology.

His comments betray an ignorance of women conductors, and of British woman conductors in particular.

Pompadours, circumstances, and late 19th century regalia: The First European Ladies Orchestra, in Vienna, helmed by the multitasking pianist-violinist-composer Josephine Weinlich.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Let’s start with Mary Wurm. Coming of age in the late 19th century and largely forgotten today, here was a pianist and composer from a musical family in Southampton. She won a Mendelssohn Scholarship for three consecutive years, enabling her to study at the Leipzig Conservatory. She moved there in 1886, taking up piano with the distinguished Romantic Era pianist Clara Schumann. In 1887 Wurm became the first woman invited to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic. Subsequently she founded and led one of the first all-women orchestras.

Such ensembles were in fashion at the time. In 1867, the Vienna Ladies Orchestra was founded by the pianist-violinist-composer Josephine Weinlich and went on to perform four years later at Carnegie Hall. Also stateside, the Fadette Women’s Orchestra was founded in Boston in 1888 by the violinist Caroline Nichols, and the Los Angeles Women’s Symphony was founded in 1893.

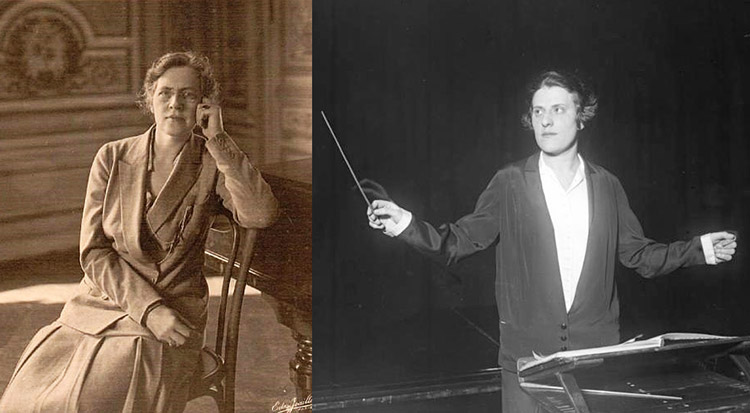

Leading ladies who were influencers in their day (and wore sensible jackets that we love): Nadia Boulanger left, who taught and inspired Leonard Bernstein and Philip Glass, among many others. Antonia Brico, right, the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic. Her many students included Judy Collins..

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Before turning to the present, let me mention three more remarkable women conductors from the past.

Nadia Boulanger, best remembered as a pedagogue, was among the founding faculty members of the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau when the school opened in 1921. She remained associated with the school for half a century, known as a teacher of harmony and composition nonpareil, with students who presented a panoply of the 20th century’s most eminent composers—among them Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, and Ned Rorem. As a conductor, Boulanger was the first woman to lead the Boston Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the BBC Symphony.

Antonia Brico, a close contemporary, worked at the San Francisco Opera on her graduation from Berkeley, and then studied at the State Academy of Music in Berlin, becoming the first American graduate of its master class in conducting. In 1938 she was the first woman to lead the New York Philharmonic, and then settling in Denver she founded the Women’s String Ensemble and served as conductor of the Denver Community Symphony—later renamed the Denver Philharmonic. Among her many students was Judy Collins, who assisted in the production of Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman, a 1974 Academy Award nominee for Best Documentary, honoring Brico’s life and career.

Sarah Caldwell, a violinist turned violist turned opera impresario extraordinary, became head of Boston University’s opera workshop in 1952 and five years later founded the Opera Company of Boston. Boston has always had a fraught relationship with opera—you wonder if this reflects the city’s puritanical beginnings and a suspicion of the most lavish of the performing arts. Nonetheless, Caldwell made opera central to the city’s already rich cultural life. With flawless artistic taste and an admirable sense of adventure, she presented—and conducted—dozens of landmark productions: Alban Berg’s Lulu in its East Coast premiere, Bellini’s I Puritani with Joan Sutherland, Norma with Beverly Sills, Prokofiev’s War and Peace in its U.S. stage premiere, Bizet’s Carmen with Marilyn Horne, and on and on. While doing all this, Caldwell also found time to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera—the first woman to do so.

Shaker uppers: Anna Rakitina, left, bringing fresh new perspectives as the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Assistant Conductor. Susanna Mälkki, right, a contemporary music specialist who’s currently chief conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic, and this season conducts what critics call an “urgent, detailed, and exciting” Rake’s Progress at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

So where are we today?

Marin Alsop, who is perhaps the best-known contemporary woman conductor, will be judged, I believe, a transitional figure. Unquestionably professional, her performances strike me as generic. They are by no means bad, but neither are they transcendent. Interpretively, they fall in the great middle ground of competent—which makes Alsop the equal of the vast majority of male conductors you will hear today.

She recently ended her 14-year tenure as music director of the Baltimore Symphony, yet remains active and respected. As well known in the U.K. as at home, she has been associated with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra as its first female principal conductor, the City of London Sinfonia, and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. She was artist-in-residence at the Southbank Centre and had the great honor of being chosen as the first woman to lead the Last Night at Proms, a British obsession rivaling that meat extract Bovril.

Building on Alsop’s considerable success, we are faced with a richness of women conductors who wed deep musicality with an ability to engage and excite their audience.

Among this cohort, Susanna Mälkki, from Finland, is most often mentioned as a potential music director. Currently chief conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Mälkki is scheduled to appear this season with the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall, as well as with the Metropolitan Opera, where she will conduct Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress. Critics rave: The New York Times characterized her performance with the New York Philharmonic as “urgent, detailed, and exciting.” To hear for yourself, listen to, and watch, her evocative and propulsive performance of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie.

https://youtu.be/9r4eeMZBInY

Anna Rakitina, a graduate of the Moscow Conservatory and a prize-winner of competitions in Denmark, Germany, and Taiwan, is Assistant Conductor of the Boston Symphony, and though she does not yet have Mälkki’s presence on the podium, she has a musical freshness that can’t be taught. To understand her success and gauge her future promise, watch her conduct a rehearsal of Haydn’s Symphony No. 90.

Surprisingly, the Chicago Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic at present have no women assistant or associate conductors.

The Philadelphia Orchestra makes up for this deficit, perhaps by having three: Assistant Conductor Erina Yashima, Conducting Fellow Lina Gonzales-Granados, and Principal Guest Conductor Nathalie Stutzmann.

The French-born Stutzmann gets around. Since 2018 she has led the Kristiansand Symphony Orchestra in Norway. In addition, she has just begun two new tenures: as Music Director of the Atlanta Symphony and as the Philadelphia Orchestra’s Principal Guest Conductor. Yet she is known less as a conductor than as a singer with a contralto voice for the ages, specializing in Baroque composers—Bach, Handel, and their peers.

Take a look, however, at the Kristiansand Orchestra’s homepage, and you’ll be pleasantly surprised. Concerts this season have standard symphonic fare but few conventional choices; several other women share the podium with Stutzmann; and there is lots of interesting new music—some Scandinavian, some American. Sir Simon Rattle, among others, has mentored Stutzmann; he said in a recent interview: “What she will do [with the Atlanta Symphony’s musicians] is give them more colors and more daring and more shape…She’s a wonderfully warm and explosive personality.”

To sample Stutzmann’s singing, listen to her performance of Cara Sposa from Handel’s 1711 opera Rinaldo. What’s more, she created the excellent orchestra Orfeo 55, heard in this 2009 performance. (Sadly, the ensemble disbanded in 2017 for lack of funds.)

Stutzmann’s arrival must be welcomed with cautious optimism. She and the Atlanta Symphony deserve great credit for embarking on what is virtually a new course. Yet for woman conductors to succeed, no matter their talent, the odds are daunting.

To an unconscionable degree, the field of classical music is shaped by a few dominant talent agencies, or in professional parlance, artist managements. They shape careers and exert outsized influence on an orchestra’s profile. Look, for example, at IMG Artists, the colossus in its field: of the 75 conductors the agency represents, six are women. Columbia Artists Management, equally prestigious, represents ten conductors, two of whom are women—Rakitina and Gonzales-Granados. As well as these eight women with representation, there are 80, or eight times 80, whose musical gifts are worthy of professional careers, but whose artistry will remain insufficiently developed.

The New York Times recently reported that ‘roughly a third of the music directors at the 25 largest orchestras in the country are planning to step down over the next several years.’ Roughly again, that’s eight music directorships that will need to be filled.

In 1968, Pat Martin, a Chicago adman with the Leo Burnett Agency, created a slogan that’s the essence of condescension, to sell Virginia Slims cigarettes: You’ve come a long way, baby. One might suspect the same of women conductors, who are paid more heed than ever before. But since the day of Mary Wurm, they still must fight for success more doggedly than men, must prove themselves doubly worthy. If much ground has been covered, there’s still a long, long way to go, baby.

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles also wrote about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: