ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Balanchine! In Book Form

Here comes a new biography—Mr. B—followed by video links to several of his mesmerizing ballets

By George Gelles

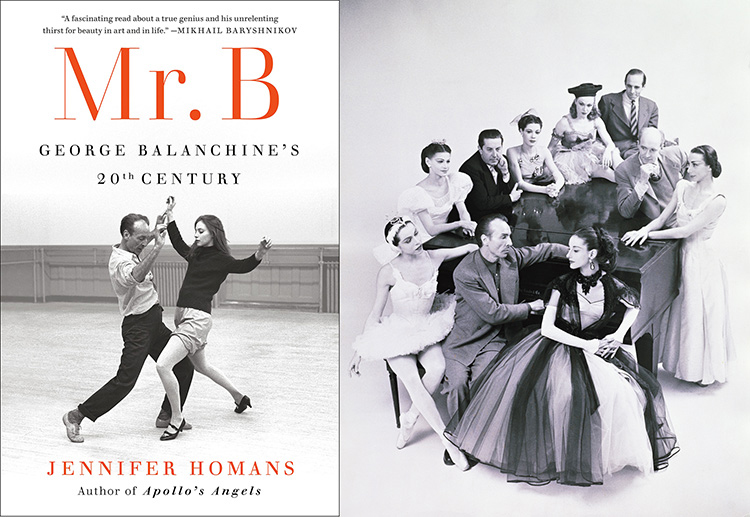

Mr. B cover: Balanchine and Suzanne Farrell, 1968, rehearsing Slaughter on Tenth Avenue. Right: Balanchine, seated between Maria Tallchief, in a tutu, and a be-gowned Tanaquil Le Clercq. Gathered around the piano, left to right: dancers Melissa Hayden, Frederich Ashton, Diana Adams, Janet Reed, Jerome Robbins, Anthony Tudor, and Nora Kaye. At the City Center, c. 1951. Photo by Ray Shorr.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dec. 26, 2022

Jennifer Homans’ Mr. B (Random House) is a blockbuster, a doorstopper, a tome. Weighing in at over two-and-a-half pounds and running to almost 800 pages, George Balanchine’s 20th Century, as the book is subtitled, is not merely a biography of a choreographer of unparalleled brilliance and a versatile man of dance. it’s an odyssey spanning centuries and continents.

In 29 chapters, Homans explores in granular detail the personal and professional events that shaped the man. We learn of Balanchine’s Russian childhood, of his fractured family and emotional deprivation; of his childhood training at St. Petersburg’s Imperial Ballet; of his progressive choreography that won the attention of impresario Serge Diaghilev, who hired him as a mainstay of the Ballets Russes; of his emigration to America and of his fateful, fruitful collaboration with the impresario-philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein, scion of a Boston fortune and a maecenas of rare vision.

Balanchine arrived on these shores in 1933. The following year, in partnership with Kirstein, he established the School of American Ballet (SAB)—which enabled Balanchine to invent—indeed, to own—classical dance for the 20th century. The SAB also emerged as a farm team, a finishing school, a feeder to fledgling dance troupes that Balanchine and Kirstein started, as well: the American Ballet Company (in 1935), Ballet Caravan (1936), the American Ballet Caravan (1941), and Ballet Society (1946). The latter companies coalesced and in 1948 became the New York City Ballet.

Homans writes perceptively of Balanchine’s relationships with some of his closest colleagues, notably the dancers Vera Zorina, Suzanne Farrell, and Tanaquil Le Clerq, as well as the dancer-choreographer-theater director Jerome Robbins. The latter two shared a tangled friendship of their own. She relates how the NYCB represented America, sometimes officially, sometimes not, on tours throughout Western Europe, South America, and Asia; and about Balanchine’s return to what by then had become the Soviet Union, whose politics he abhorred, whose people adored him and his dances.

A one-time student at the School of American Ballet, Homans seems to have spoken compulsively with everyone who ever entered Balanchine’s orbit. We hear from dancers and choreographers, from artistic administrators and foundation benefactors, from impresarios and intendants, from critics pro and con, from those backstage and behind the scene.

At its best, the book paints vivid portraits of Balanchine’s intimates as his company gained prominence, first at the New York City Center on West 55th Street, and then, as now, at Lincoln Center. As the company grew, it was managed by an able troika. Betty Cage was primus inter pares, the executive director in today’s parlance, and Barbara Horgan in time signed on as her assistant. Eddie Bigelow transitioned from dancer to all-around factotum.

The dancers were of diverse and dizzying backgrounds, coming from the country’s every nook and cranny, some with solid training, others not. As they honed their skills and coalesced, they became the means by which Balanchine found his voice and his vision, even as his ballets let each dancer express her or his own essence.

Homans introduces us to many of those prominent in the NYCB’s early iterations, including Una Kai, Janet Reed, Yvonne Mounsey, Patricia Wilde, Melissa Hayden, Diana Adams, Tanaquil LeClerq, Allegra Kent, Jerome Robbins, Francisco Moncion, Todd Bolender, Jacques d’Amboise, and Arthur Mitchell. Some names you will recognize, others not. Each is well worth meeting.

Homans, too, is excellent in letting us experience dances through her eyes, as we see in the following two, among many, vignettes.

Balanchine and Suzanne Farrell in Don Quixote for the New York City Ballet, 1965.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

First, she devotes an entire chapter to Don Quixote, “a monster of a production,” in which Balanchine was Quixote and Suzanne Farrell his Dulcinea. Farrell had joined the company as a teen in 1961 and became recognized as Balanchine’s ideal dancer—his ideal woman—and was cast in all major roles. She left the company for Europe eight years later, when tensions between personal feelings and professional obligations caused an irreconcilable impasse. In 1975, she returned and resumed her place as the brightest star in Balanchine’s galaxy.

Don Quixote, created for Farrell in 1965, was a telling tribute to the dancer he loved most, though the woman he could never have. Despite a mixed reception from critics, the piece was a landmark—a public revelation from an essentially private man. Its final moments, when Dulcinea attends to the dying Don, were as personal and heartbreaking as any of Balanchine’s dances.

Second, Agon. Here too, Homans offers an excellent report on an ill-starred venture that took the NYCB to Berlin, where 15 Balanchine ballets were filmed for a German production company. I can vouch for her observations’ veracity, as I was privileged to attend the shooting of Agon, perhaps the most significant collaboration between Balanchine and composer Igor Stravinsky. Homans’ Agon chapter is superb, both in her description of the dance’s genesis and in her discussion of the difficulties it encountered in Berlin.

The situation was as she describes. Balanchine had one idea about how dance should be filmed, the producer a different notion. Balanchine sought something akin to documentary, the producer something more like entertainment, an approach that distorted the dance’s symmetries and design in a ballet where design and symmetries are everything. That these differing outlooks weren’t earlier discussed remains a puzzlement. The producer had videotapes and scores of the ballets beforehand and surely knew the works. Regardless, their visions were incompatible, and the results pleased no one.

If Mr. B is exhaustive, it is exhausting too. The most ardent balletomane might savor every detail, but for a book in search of a general readership, there is too much incidental information that saps the book’s strengths. Do I care that Balanchine grew rubber plants in mayonnaise jars? Or that late in life he had a bald spot that got a comb-over? Or that he now rests in a cemetery that’s near a different burial ground where famous painters are interred? Three times, no.

Trivial pursuits and all, however, the book will be a reference, and I hope future printings will correct two typos—the gremlins that sneak into virtually all manuscripts: composer Hershey Kay’s given name is misspelled as Hersey on page 340 (with the wrong page listed in the index); and on page 570, composer Robert Schumann attempts suicide “by leaping into the ocean …” In fact, it was the River Rhine.

Should you wish a less daunting introduction to Mr. B, I’ve nothing but praise for Robert Gottlieb’s Balanchine (Harper Perennial), originally published in 2004. With only about a quarter the heft and a quarter the length of Homans’ opus, Gottlieb provides a fully fleshed out portrait of the master choreographer. Much as did Homans, he traces Balanchine’s life and work, but his writing admits nothing extraneous. His prose flows and captivates, even as his critical eye informs.

His viewpoint is unique. For years, Gottlieb served on the Board of the NYCB, and his opinions were so trusted, his knowledge so deep—of the choreographer and his dancers, their repertory and the ethos they shared—that Balanchine welcomed his collaboration on programming the night to night repertory. His volume is essential, enjoyable reading.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

As wonderful as it is to read about Balanchine’s ballets, it is even more wonderful to see them. Our gratitude to YouTube for making available these five videos, among many others, one from each of five fecund decades:

Apollon Musagète (Apollo as Leader of the Muses) was originally made for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1928, and became the first of a remarkable triptych created by Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky. It was altered by Balanchine over the years. But the original, with scenes depicting Apollo’s birth, and, with the Muses, his ascent at the end, is seen in this 1965 NYCB performance from Hamburg, with Suzanne Farrell and Jacques d’Amboise.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Slaughter on Tenth Avenue was first seen in the Rodgers and Hart musical On Your Toes (1936), and it reminds us how active Balanchine was both on Broadway and in Hollywood. In the stage production, as in this version from 1939, the dancehall girl was actress-ballerina Vera Zorina—sleek, sultry, irresistible.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Orpheus (1948) presents the musician-poet of Greek myth as he attempts to rescue his wife, Eurydice, from Hades. It is the centerpiece of the Balanchine-Stravinsky triptych (Agon completes the trio that begins with Apollo), and perhaps the purest of the three. Isamu Noguchi, renowned sculptor, designed the sets and costumes, and one image is indelible. As Orpheus starts to lead Eurydice from the Underworld to the realm above—they are danced in this excerpt by Nicholas Magallanes and Violette Verdy—a stage-wide sheet of silken fabric floats down from the flies. (Memory remembers the silk wafting more leisurely than here.) Seeing the piece for the first time at the City Center was magical.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Square Dance (1957) has been stripped of its original costumes and setting—and of its square dance caller, too—but this televised performance of the original is special for its spirit and style, and for the wonderful dancing of Patricia Wilde.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Tarantella (1964) was choreographed for Patricia McBride and Edward Villella, and though other dancers have inherited the roles, no performance achieves the stylistic authenticity seen here, in a performance captured from a television screen—the rounded corners of the image are a giveaway.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

We’ll leave the last words to Robert Gottlieb. Towards the end of his wonderful appreciation, he writes that “… as the work of his immediate predecessors and near contemporaries—Fokine, Massine, Nijinska, et al.—seems to recede into history, Balanchine is more and more left standing alone, a giant figure whose work and influence impose themselves everywhere on the art he loved and transformed.”

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles also wrote about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: