ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Why Dance Matters: A Soaring Review

Celebrating a book that itself is a celebration

By George Gelles

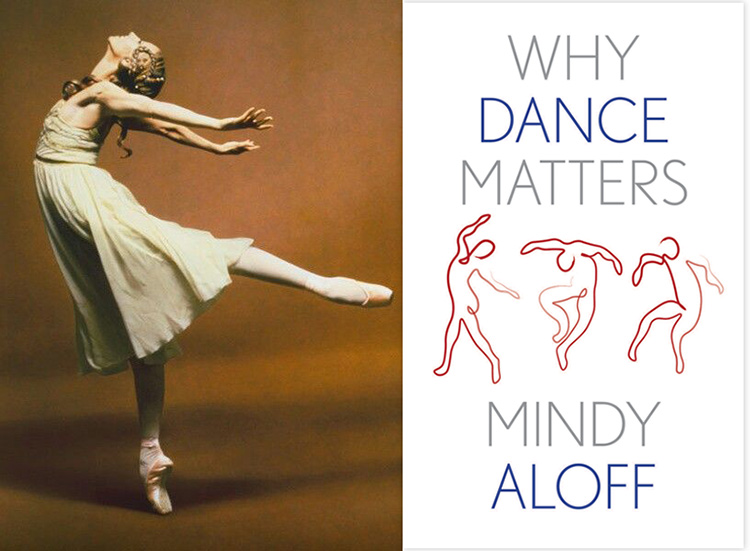

On her toes: Natalia Makarova in Romeo and Juliet. Photo by Dina Makaroff.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

April 13, 2023

Mindy Aloff’s Why Dance Matters (Yale University Press) is a magnificent achievement. Of the more than 500 dance books I once owned that taught me much about the art—they are now the possession of the University of California, Santa Barbara—this volume would have ranked near the top for its intellectual prowess and keen curiosity, for its thoughtful perceptions and pellucid prose.

The arc of the book traces the story of a girl smitten by dance as a teen, who went on to meet or speak with virtually every performer of artistic significance, to chart every fad and fancy over the course of six decades as one of our preeminent writers on dance.

Every page provides food for thought, but space allows mentioning just a few of Aloff’s observations.

Writing of the transcendent moments that keep us in thrall to dance, she observes that for a dancer to learn a piece, step-by-step-by-step, is an arduous, logical, left-brain process, after which the dancer “must somehow also, on some level, illogically connect, instantaneously and mysteriously,” with an audience.

“It continues to amaze me,” Aloff says, “that a few individual dancers, such as Anna Pavlova or Margot Fonteyn or Michael Jackson, effect that immediate connection worldwide, inspiring appreciation among millions of individuals who could never communicate with one another through verbal language…but who all immediately understand the dancer.”

With an audience of several thousand others, I experienced such a moment myself. Back in the 1970s, when the American Ballet Theater visited the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., it presented Antony Tudor’s Romeo and Juliet, a work created in 1943 and now irretrievably lost. The curtain rose on Eugene Berman’s poetic sets and costumes, inspired by Botticelli, while Frederick Delius’ atmospheric music swathed the story in gorgeous, gauzy sound. Momentarily, Juliet entered the stage to our left—the evening’s Juliet was Natalia Makarova—and at center stage she elevated herself to half-point—and 2,300 people gasped as one. Aloff elsewhere cites a gnomic aside uttered by George Balanchine, and it’s apropos here, in which he refers to “a certain kind of stage illusion associated with magic, music, and what was once called the sublime.” This brew was the alchemy of the moment.

Throughout her book, Aloff calls attention to steps, not necessarily to dance steps but to the steps that we take when we walk. She quotes Senta Driver, a mainstay for six years of Paul Taylor’s dance company until she left in 1973 to found her own troupe, called Harry. In response to Aloff’s question about the inspiration for Memorandum, her solo dance for Harry that consists of ritualistic clockwise pacing, as if in a cloister, Driver had a ready answer: “Walking! It’s the first thing you do”.

The great composers knew this, and none more so than Schubert, whose Die Winterreise—The Winter Journey—presents a song cycle’s catalogue of ways to walk: songs amble, stroll, and saunter, they tramp, tread, and trudge. With her cue from Driver, Aloff catalogues and comments on some of her own favorite walking dances—works by Mark Morris, George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton, Martha Graham, David Gordon, and others.

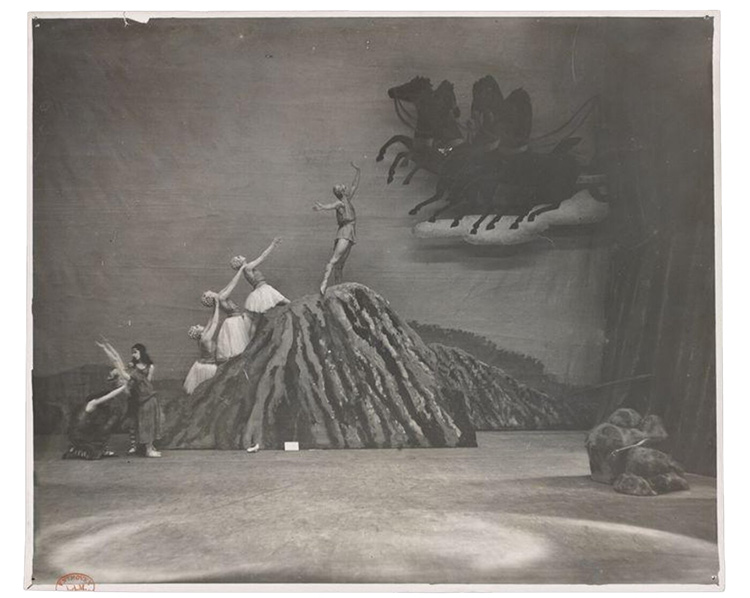

Climbers: Stage photo of the final pose from Apollon Musagète, performed by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, June 1928.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

An example worth a closer look is the walking procession that closes Apollo, the 1928 collaboration between Balanchine and composer Igor Stravinsky. The episode depicts Apollo and the Muses as they prepare their ascent to Parnassus. As the dancers’ stately paces move them ever more distant from us, Stravinsky paints the scene in sound. Six measures before the piece ends, you’ll hear a motif high in the violins; they sustain a long note for three beats; then they repeat the motif, sustaining the long note for four beats; then for five, for six, for seven, and for 11 as the curtain descends. The distancing choreographed by Balanchine is composed by Stravinsky. What the eye sees, the ear hears.

Aloff’s eloquence is reserved not just for classical dance. She writes with enthusiastic acumen about the offbeat and the avant-garde, about modern dancers and moviemakers.

Her subjects include wire-walker Philippe Petit, Fred Astaire, Elizabeth Streb (“Can you fall up?”), filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi, Paul Taylor, Arthur Mitchell, Twyla Tharp, anyone and everyone.

Happy landing: The scene set in the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles, from The Artist a 2011 French comedy-drama film.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The incontrovertible takeaway is that dance is where you find it. Me, I find endless pleasure in a scene from The Artist, which won five Academy Awards, including that for Best Picture, in 2012. In the 37th minute and for two minutes more, there’s a scene shared by the movie’s leads, George and Peppy (played by Jean Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo), as they meet on a landing between floors in the Bradbury Building, the great 1893 Los Angeles landmark building whose capacious atrium is illuminated by a skylight’s soft luminescence, and whose interior still is vibrant with ornamental ironwork, Italian marble, Mexican tiles, Spanish sconces, polished wood.

The actors are central to the scene, but the real stars are the dozens of anonymous extras whose comings and goings—from floor to floor, across the landings, up the stairs and down—cannot be haphazard. They are choreographed to a fare-thee-well, and the tapestry of their patterns is beautiful in design and execution.

Why dance matters? Because, as Aloff generously illustrates in myriad examples, it allows us to examine more closely, and feel more deeply, the world in which we live.

George Gelles was the dance critic of The Washington Star from 1970 to 1976 and the author of A Beautiful Time for Dancers. He thinks of himself basically as a musician—a horn player—who just happened not to play professionally for 37 years. Gelles has also written about music and dance for The New York Times, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Musical America, and lectured on music and dance at the Smithsonian, George Washington University, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. And from 1986 to 2000, he was the executive director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

You may enjoy other stories by George Gelles: