ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Woman of Heart and Mind…and Ego

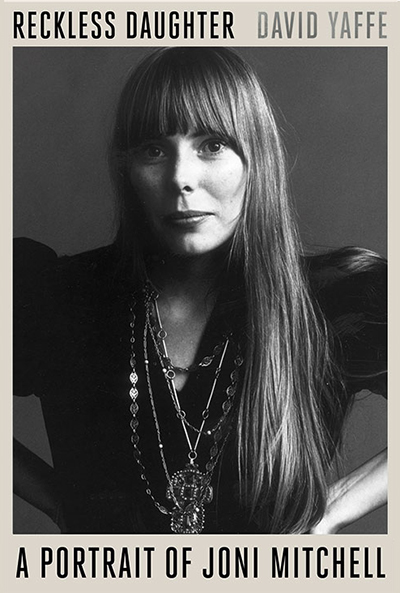

A biography of Joni Mitchell, Reckless Daughter by David Yaffe, tells uncomfortable truths about the only songwriter in the same league as Dylan.

By Grace Lichtenstein

Some pop culture idols never grow old. Janis Joplin, for instance, remains the bangled 27-year-old hippie chick with a style borrowed from Bessie Smith. James Dean is still 24, the coolest rebel of his generation.

Some pop culture idols never grow old. Janis Joplin, for instance, remains the bangled 27-year-old hippie chick with a style borrowed from Bessie Smith. James Dean is still 24, the coolest rebel of his generation.

And then there is Joni Mitchell, 74, sick, hostile and ungrateful.

For those of us who have worshipped her work, it’s heartbreaking. The fresh-faced young Canadian with long flaxen hair and the soprano voice that could leap octaves suffered an aneurysm in 2015. At last check, she was still recuperating. Her lifelong cigarette habit reduced her voice decades ago to contralto.

And if David Yaffe’s new biography is accurate, what’s shocking is how she seems bent on badmouthing nearly everyone who had been close to her, as if her ego can only be propped up by knocking others down.

She is hardly the only icon of her era in decline. Bob Dylan at 76 no longer looks freewheeling’ and his voice was never his strong suit. He continues to perform, however, and of course he is a Nobel laureate. Mitchell’s lifetime of lyrics are easily of that lofty caliber. Reckless Daughter does them justice. The author closely analyses Mitchell’s songs, album by album, including her open guitar tunings that created a unique sound.

Yaffe has the advantage of face-to-face interviews with Mitchell, including sessions in 2015, just before her illness. (He was allowed back into her life even though she disliked a New York Times article he wrote.) Absent an autobiography—she told people the first sentence would be “I was the only black man at the party,” a reference to the photo of her posed as a pimp on the cover of the album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter—this may be as close as readers get to her complicated persona.

Roberta Joan Anderson was born Nov. 7, 1943 in Alberta and grew up in Saskatchewan. The defining event of her childhood was a bout of polio at the age of 10. She was confined to a hospital for months; her mother visited her just once. Painting and drawing were her primary artistic activities growing up, although she bought a ukulele and taught herself to play. She never attended college and dropped out of art school.

The key event of her very young adulthood was an unplanned pregnancy. Her song “Little Green” refers to Kelly (now called Kilauren), the daughter she put up for adoption in Toronto in 1965. Her new husband Chuck Mitchell, who was not the child’s father, brought her to the United States. She thought they could raise the child together; Joni left him when he said he wasn’t cut out to be a parent, but she retained his name.

After moving to New York, she began attracting attention, playing in Greenwich Village clubs and the Newport Folk Festival. She acknowledges that Dylan’s early songs made her realize that the idea of “storytelling” and “personal narrative” was possible in her music.

Her earliest big break came in 1967 after musician Al Kooper listened to her sing “Both Sides, Now” (inspired by a phrase from Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King) in her West 16th Street apartment. Astounded, he immediately phoned Judy Collins, even though it was 3 a.m., insisting that she listen as Mitchell sang it over the telephone. Collins, who was in the midst of recording an album, recalled “I went crazy and said, ‘I must have that song.’”

Already a force in pop music, Collins immediately added “Both Sides Now” to her album and won a Grammy for it. According to Yaffe, “Joni was not impressed,” commenting, “There’s something la-di-da about her.” Collins, who also helped bring Joni to Newport, asked why Mitchell would “slam the person who did the biggest favor of her career?”

Why, indeed. Throughout, Yaffe catalogues Mitchell’s wide range of insults. David Crosby, a lover who produced her first album: “paranoid and grumpy….unattractive in every way” after they broke up. Jackson Browne: “leering narcissist.” James Taylor: “incapable of affection.” Second husband Larry Klein: a “puffed up dwarf.” She disputes details in stories told about her by Graham Nash, who wrote “Our House” about their idyllic home life in Laurel Canyon, although she is kinder toward Nash than toward some producers, journalists and other musicians.

True to her lyrics, Mitchell really could “count lovers like railroad cars.” The list included Leonard Cohen, Taylor, Crosby, Nash, Browne, Sam Shepard. She wrote songs about many of them. Most of her friends seemed to be men. Nevertheless, as a woman in the very macho music business (“the star-maker machinery of the popular son,” as she called it in “Free Man in Paris,”) she has always been aware that men are bent on manipulating female musicians. She wanted to get as far away from that machinery as she could.

Leaving Graham Nash, she traveled abroad, spending time in a cave at Matala on Crete, among other places. Out of this came Blue, the album many consider her masterpiece. It grew, she said, out of her deepest depression.

Her third album, Ladies of the Canyon, included “The Circle Game” and “Big Yellow Taxi” and won her a greater degree of recognition. Yet, she said, “my individual psychological descent coincided, ironically, with my ascent into the public eye. They were putting me in a pedestal and I was wobbling.” With Blue, “I took it upon myself that since I…was subject to this kind of weird worship, they should know who they were worshipping. I was demanding of myself a deeper and greater honesty, more and more revelation in my work.”

If, as the title song of Blue says, “songs are like tattoos,” we, Joni’s worshippers, are covered with the ink of “All I Want,” “Little Green,” “A Case of You,” “River,” “My Old Man” and “Carey.” Bob Dylan said that when he was writing “Tangled Up in Blue,” he was tangled up in Joni’s Blue, writes Yaffe. The biographer compares the album to Picasso’s Blue period.

Whether Mitchell likes the biography or not, surely she likes this analogy. Her ego is as outsized as her talent. According to Yaffe, she compared herself to Van Gogh, Picasso, Miles Davis and Beethoven. As David Crosby once said, she had the “modesty of Mussolini.” Her self-portrait, bandage on her ear, on the cover of Turbulent Indigo, mimics Van Gogh.

The late 1970’s and early 1980’s marked a divide for Mitchell. She mostly turned her back on her pop folk style, playing jazz with musicians like Wayne Shorter instead. It was not a change welcomed by many fans. But she admonished them, “nobody ever said to Van Gogh, ‘Paint a Starry Night again, man!’”

Is that fair? Yaffe notes that no one bought “Starry Night” in the first place. “Many people bought Court and Spark [her 1974 album that reached number two on the Billboard charts] and now she’s given the luxury to express contempt for the people who made her popular.” Besides, Van Gogh always painted in the same style; Joni changed her sound despite warnings from advisers like David Geffen that her fans would desert her. Other pop stars have made more successful transitions. When Dylan flipped from acoustic to electric, he alienated part of his public. They eventually returned; Joni’s fans did not return.

In a 1991 Rolling Stone interview, Mitchell said that what she had in common with heroes like Picasso and Miles Davis was restlessness. “I don’t know any women role models for that. Most of my heroes are monsters, unfortunately, and they are men.” Indeed, Dylan once commented that Joni was “almost like a man. I mean, I love Joni, too,” he continued. “But Joni’s got a strange sense of rhythm that’s all her own and she lives on that timetable. Joni Mitchell is in her own world all by herself.’

Yaffe covers the years from 1976 to 2016 quickly. There were more albums, collaborations, awards and honors, plus a reconnection with her daughter. Still, “Everything comes and goes / Pleasure moves on too early / And trouble leaves too slow,” she muses on “Down to You.”

In the end, what remains is the music, from the giddiness of “Night in the City” (1966) to her husky, sultry reprise of “Both Sides Now” (2000). “Will you take me as I am?” she asked on Blue.

Yes, as a monster—and a genius.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell by David Yaffe; hardcover; 420 pages; Publisher: Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus and Giroux; October 2017.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Grace Lichtenstein is a former New York Times reporter and bureau chief, the author of six books and a contributor to numerous national magazines.

You may enjoy other NYCitywoman articles by Grace Lichtenstein:

‘Battle of the Sexes’ Tennis, Triumph, Trauma

Seven Truly Essential Apps for Your iPhone

Best Books About New York City

Touring France With Comfort On An E-Bike

The Year of Voting Dangerously

November 8th, 2017 at 7:54 pm

Really interesting article on Joni Mitchell. Takes me happily musically back to mid ’70’s.

November 13th, 2017 at 9:49 am

Fascinating.