ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Just in Time for Summer: Book Reviews!

Recalling the ’60s, two very different takes on women’s rights and feminism—one fiction, the other non-. And harking even further back, a guide to Victorian flower lore, replete with 19th century botanical drawings—given a surreal spin.

The Victorians—with their standards of modesty and respectability (not necessarily adhered to)—made a habit of communicating in code. Messages were conveyed in the wielding of fans, in the angles of stamps placed on envelopes, and, most alluring and complex of all, in the extensive non-verbal language of flowers and bouquets— known as floriography. Presenting a bloom with the right hand meant It’s on! With the left hand? Nah. The visual artist Karen Azoulay has now written a decoder guide, Flowers and Their Meanings: The Secret Language and History of Over 600 Blooms (Penguin Random House). But this 21st century route into Victorian flower lore is more than a reference book. At the start: a series of Azoulay’s ad hoc essays and quick takes uncover some of the history, aesthetics, pleasures, and proclivities of the Victorian era and its later impact. It’s noted, for instance, that Diana Spencer, Princess Di’s, wedding bouquet contained two barely visible canary-yellow roses—signifying jealousy and infidelity. (She knew!) One of my favorite sections? Global Botany Expeditions. The Empire brought plunder to the colonies. In partial return, the subject nations introduced to Britain and continental Europe a bounty of blooms (an unfair exchange, to be sure). The main part of book is an alphabetical recounting of flowers (as well as herbs and other budding plants) and their fabled attributes. The Enchanter’s Nightshade signals sorcery; jasmine announces amiability; and Shooting Star claims you are my Divinity. On the negative side, Cockscomb connotes foppery, while Gentian conveys I Love You Best When You Are Sad. (Huh?) And then at the end is a delightful themed index, with such listings as Commitment, Flirtation & Sensuality, and Insults & Loathing. Extrapolating from that last category, the gift of a bouquet of Bee Balm and Frog Orchid would announce Your whims are quite unbearable, and Disgust, respectively. Oh no! Given in jest perhaps?

The flowers on display are 19th century botanical drawings, intermingled by Azoulay with photographic images of faces, eyes, mouths, and hands—creating a surreal effect. I reached out to her, asking what she had in mind here. Her response: Like flowers, these anatomical additives are communicators. “The 19th century botanical illustrations are so gorgeous, but I wanted it to be clear that this was a new take on the topic—not just another Victorian flora book.” (Of which there are many.) Azoulay is right. Her book is beguiling, full of surprises, revealing intimate details of a bygone culture that wasn’t as stuffy as we may think. –Linda Dyett

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

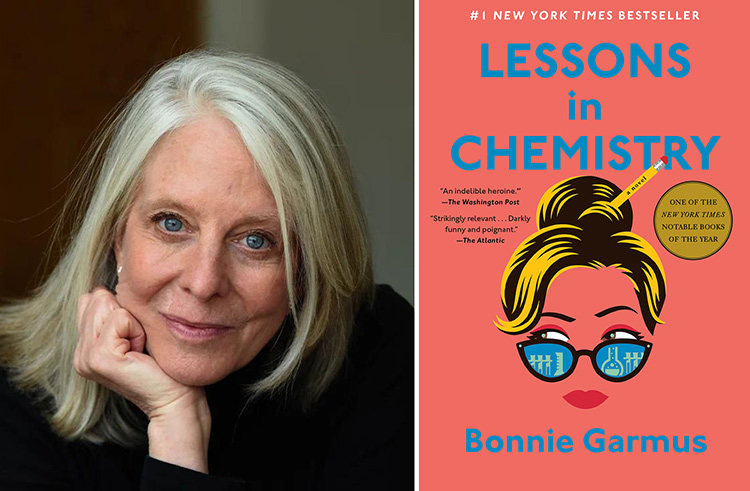

Can a wildly popular novel—a Number One New York Times bestseller for months—actually be a terrific book? The answer is yes, if that book is Bonnie Garmus’s Lessons in Chemistry (Doubleday). Here is a feminist heroine for the ages—one Elizabeth Zott, a brilliant research chemist stymied by a sexist system.

Zott winds up becoming a TV chef—a signal demotion in her own eyes. She has turned her home kitchen into a lab. So when she is first approached about doing a TV show, she has other things on her mind. “I have something in the cyclotron,” she said irritably, glancing at her watch. “Do we have an understanding or not?”

She also has a dog named Six Thirty who has his own thoughts, and a precocious daughter. She refuses to marry her Nobel-nominated love, Calvin Evans, because she does not want to be subsumed in his brilliance. All this takes place in the early 1960s, where sexism was mother’s milk and women did not necessarily get ahead in their chosen fields.

As one reviewer noted, the point is: “better living through casseroles.” Although Lessons in Chemistry is clearly aimed at women, it is not a typical women’s novel. Underneath its comic exterior is a serious point. Garmus writes, “People always yearn for a simple solution to their complicated problems. It’s a lot easier to have faith in something you can’t see, can’t touch, can’t explain and can’t change, rather than to have faith in something you actually can.” There is no huge complexity in Lessons in Chemistry, but much to make you laugh. –Grace Lichtenstein

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

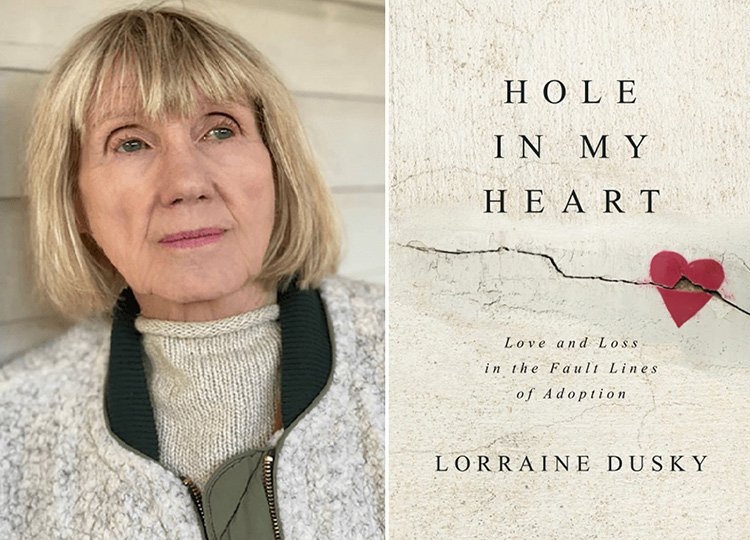

Lorraine Dusky’s timing was perfect, in the saddest of ways.

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, held that the U.S. Constitution does not confer a right to abortion—thus reversing Roe v. Wade. The ruling upset abortion policy, and also the procedures and politics of abortions. Denial of a woman’s right to choose made headlines across the country.

At that very time, Dusky was finishing a revised version of her 2015 memoir Hole in My Heart: Love and Loss in the Fault Lines of Adoption (Grand Canyon Press), about the lifelong impact of her decision, as a young journalist who became pregnant by a married co-worker. In the years before Roe v. Wade, she reluctantly decided to give up her daughter for adoption.

In the updated 2023 version of her memoir, Dusky details what she went through to find and reunite with her child. “I had a baby and I gave her away. But I am a mother.”

Adding 30,000 words to her original work, Dusky reviews the problems—psychological, personal, legal—facing women who have given up a child for adoption. In 1975 she wrote an op-ed piece for The New York Times about giving up her daughter, Jane, who was born in 1966. One of the first in those days to “come out,” she soon landed—on The Today Show and a bevy of other TV shows—to talk about this controversial topic. (She also published her first memoir, Birthmark, 13 years after Jane was born.) Her desire, then and now: “to have people re-think about what adoption is like for both the mother who gives up the child and the adopted person.” She adds, “I’d like people to know that adoption is really a difficult thing.”

Through The Searcher, an underground agent, Lorraine managed to obtain information about who had adopted Jane that was unavailable to the public. As it happened, she had just sold her cherished beige MG, and with the proceeds—$10,000—she could pay the fee.

The connection was magical and heartbreaking: the adopting couple, now in Wisconsin, tell Lorraine that Jane has epilepsy and consequential learning problems. They invite her to their home, to meet them and Jane, and eventually the rest of the family. For many summers, Jane visits Lorraine and her husband Tony Brandt in Sag Harbor, on the South Fork of Long Island. There was love, as the title suggests, but also loss: Ultimately Jane committed suicide.

Over the years, Dusky has consistently written and spoken for the rights of birth mothers and adopted children. Along with others, she successfully pushed to change the law of closed adoptions in New York; in 2019, the New York State Assembly passed a bill allowing adoptees over age 18 to gain access to their birth records, including information about the birth mother.

In 2022, Justice Samuel Alito wrote in his Dobbs v. Jackson decision, “a woman who puts her newborn up for adoption today has little to fear that the baby will not find a suitable home,” adding, “there is a shortage of available babies.” His clear implication: solving the problem for those wishing to adopt is more important than women’s autonomy over their own bodies.

A supporter of Roe v Wade, Dusky sees the six justices’ repeal not only as an attack against women’s autonomy over their own bodies, but as causing great harm to the women who must give up their babies—and to their adopted children.

To date, only 13 states allow adoptees access to their original birth certificate. In the other states—many that are limiting or banning abortion—access is denied or has restrictions. Dusky’s book is a reminder of what has been lost, what troubles for adoptees and birth mothers lie ahead—and what must be fought for, in the courts and in elections. –Suzanne Charlé

You may enjoy other NYCitywoman book reviews: