ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget … The Grateful Dead and Summer of Love

In 1969, it was all psychedelic joy with the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane at Golden Gate Park—only to be followed by violence when peaceful Berkley protesters were overcome by National Guardsmen armed with unsheathed bayonets and live ammunition

By Suzanne Charlé

The Grateful Dead in performance mode, tambourine at the ready on top of Pigpen’s Hammond B3 organ. Photo by Zuma Press.

January 26, 2024

January 26, 2024

Berkeley, May 7, 1969. For weeks, in between classes, friends and I, along with other students and even professors, had been working and playing on a tattered block not far from campus. In People’s Park, we planted trees and flowers, built picnic tables, had impromptu music jams, played. The university planned to make the park an athletic field, but we had better ideas. In the midst of a Frisbee free-for-all, we heard that a free concert was going to be held in Golden Gate Park. A bunch of us hopped into a VW bus and crossed the Bay Bridge to San Francisco.

By the time we arrived, hundreds, then thousands, were crowding onto the field. Almost all of us were in bell bottoms and tie-dyed T-shirts, and some, as the song goes, had flowers in their hair. Onstage, the Grateful Dead sported even more colorful attire. Remember the psychedelic cover of their debut album?

Jerry Garcia, the Dead’s lead singer and guitarist, and the rest of the band wove an improvisational tapestry of love, delight, and hope for America. In tune with “Turn On Your Lovelight” and “Morning Dew,” attendees painted colorful designs on friends’ faces and danced with wild abandon, exploring new moves as the band explored new sounds.

In between songs, the musicians jammed—a melodic, rambling, explosive kind of music, mixing jazz, folk and rock, bluegrass, and reggae: “Dark Star” was a standout. Guitars were played with incredible speed, the music a loud, trippy salute to joy. Some guys launched soap bubbles—a thousand times larger than any bubbles we blew as kids—that flew across the crowd; I thought they (the bubbles, not the concertgoers) would explode with the wild sounds and movements of the crowd, but they didn’t: Everything was all about fun, joy, life.

Every once in a while, band members would stop to take a toke. (From what I could see, the drummer, Bill Kreutzmann, was smoking nonstop.) In fact, the air was filled with smoke: Some ingenious folks had brought a garbage can filled with marijuana, lit it, and offered it to all of us to inhale via three or four garden hoses. Garden hoses!

Back in 1964, accompanied by two of my high school best friends, my mother, and my brother, I was lucky to see the Beatles in Atlantic City—in one of the concerts on their first American tour. It was spectacular—though I heard more of the screaming crowd than the songs. I loved it!

But this concert in San Francisco was totally different, and not just because my mother wasn’t there. It was free, a quickly organized get-together—no PR, no tickets or lines to stand on. The feeling was totally counterculture and cool. I think I saw Allen Ginsberg, a great friend of the Dead. Jefferson Airplane showed up, too—the Haight-Ashbury group that defined the San Francisco Sound. We all joined in, linking arms, as Grace Slick sang “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit.” Even the cops caught the vibe: Throughout, they stood outside the field, watching calmly; one near me peered down, smiling. We danced and sang: The Summer of Love was alive and well.

Or so we thought. Eight days later, the university police cleared out People’s Park and quickly cordoned off the space with a chain-link fence. On May 16 at noon, thousands of us marched peacefully in protest. The police responded with tear gas and buckshot. On Bloody Thursday, a local resident, James Rector, was on a roof when police shot him; he later died. Fifty-eight others were hospitalized. Berkeley had become a bloody war zone. Martial law was declared, a curfew was imposed, and National Guardsmen armed with unsheathed bayonets and live ammunition took over.

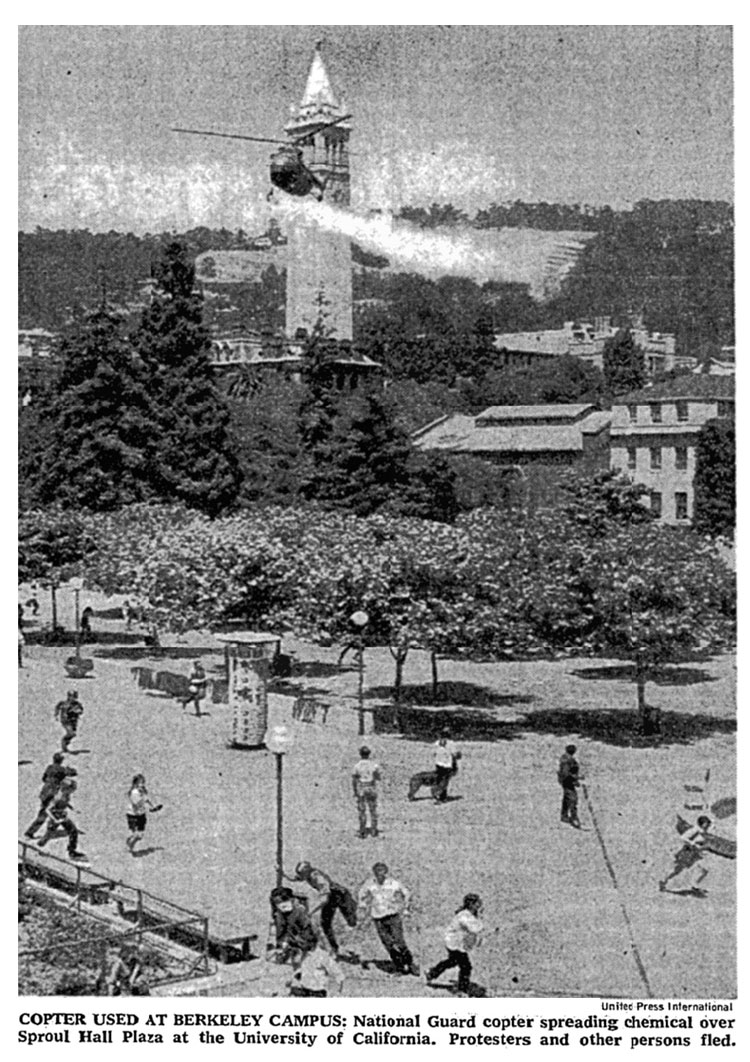

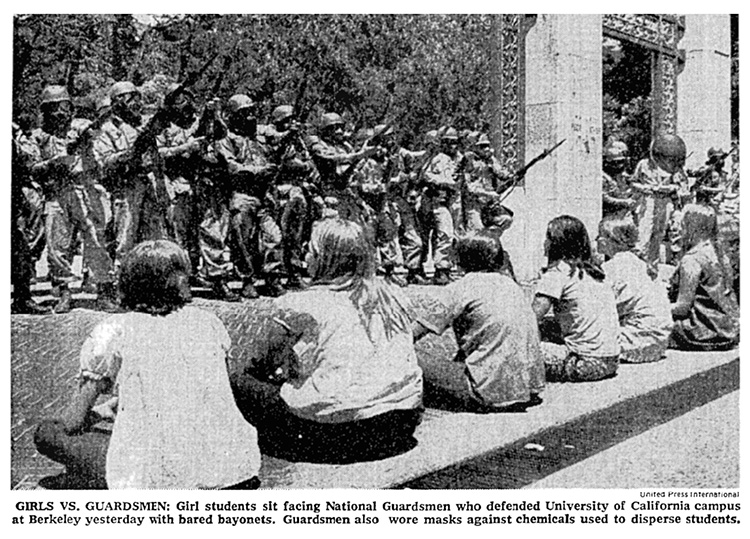

The next day, hundreds of us showed up at Sproul Plaza to protest. Local police surrounded the plaza. The National Guard, complete with guns and gas masks, lined up along Sather Gate, blocking entrance to the Berkeley campus. Some other young women and I, worried that the boys behind us might accidentally be pushed into the bayonets, sat down in front of the guards, pleading for them to leave. A short time later, a crop duster circled the Campanile and then, on Governor Ronald Reagan’s orders, flew over the plaza, spraying us all with CN gas—a chemical weapon. The Summer of Love was off to a rough start.

Copter Breaks up Berkeley Crowd, headlined The New York Times in its May 21, 1969 coverage of the campus tear gas and buckshot attack.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Girls vs. Guardsmen. A May 21, 1969 New York Times photo displays a lineup of women students at Berkeley, facing a National Guard armed “with bared bayonets,” as the Times caption notes.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

“People’s Park War”. A Public Broadcasting video of the protest at Sproul Plaza. The author is present, with her arm outstretched.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Somehow I made my way off campus, past the barbed wire that had been put up, coughing and uselessly rubbing my eyes with a wet cloth someone gave me. I finally made my way up a steep hill and walked into the International House, where I lived. As soon as I entered the café, everyone around me started coughing—I was a walking gas bomb.

Throughout the night, I coughed and threw up. Finally I fell asleep, only to be wakened by someone knocking on my door at 5 a.m.

“Phone call—it’s your mother.” (This was, remember, long before cell phones; there was one phone for all of us.)

I climbed down from my bunk bed, went into the hall, and picked up the phone. “Hi, Mom. Why are you calling? You do know it’s three hours earlier here than in New Jersey.”

“I just wanted to hear how things are,” she replied.

“Fine, Mom, just fine.”

“Oh? Then why are you on the front page of The New York Times?”

Taking a deep breath, I explained everything that had happened.

My mother responded quickly: “Suzi, promise me you won’t go out again today.”

“Mother, I have to.”

A brief pause. “All right. Then I have just two things to say,” Mother replied. “Watch your back.”

“Yes?”

“And give them hell.”

Later in August, the three-day Woodstock Music and Art Fair—which came to be known simply as Woodstock—turned into a larger, more organized (the bands were paid) festival, which was actually held on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York, 40 miles south of Woodstock. It had much of the same vibe as the Golden Gate get-together, with crowds so large that Governor Nelson Rockefeller was going to send in 10,000 National Guard troops. Luckily, the organizers persuaded him not to follow through, and, while very wet, all was peaceful, with Jimi Hendrix performing a searing version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” This festival marked the height of the Summer of Love.

Less than four months later, the Rolling Stones, along with Jefferson Airplane, put on a free rock concert at the Altamont Speedway in Northern California. This time, the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang replaced the National Guard as “security.” More than 300,000 fans showed up. Trouble started early, with some of the Angels running over and killing two kids in sleeping bags. That was followed by an LSD-related drowning in a drainage ditch. And when a 21-year-old Hell’s Angel stabbed a fan to death during the Stones’ appearance, the Summer of Love was truly over.

On upper right: photo of Jerry Garcia by Carl Lender.

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including The Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the Magazine. She has co-authored many books, including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

For other NYCitywoman articles by Suzanne Charlé, see: