ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Hotbed: How Women Got the Right to Vote

An up-close look at Greenwich Village in the early 20th century and the activists who were young, sexy and ready to break the rules to obtain women’s right to vote.

By Suzanne Charlé

Women’s Suffrage Parade on October 23, 1915.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

When New Yorkers lined up at the polls to vote this year, they were also paying tribute to 1917, the centennial of the bill that gave women the right to vote in New York State. Three years later, in 1920, the 19th Amendment granted all U.S. citizens the right to vote “regardless of sex.”

But surprisingly, New York State was not the first or even the second to give women the right to vote, notes Joanna Scutts, who, along with Sarah Gordon curated “Hotbed,” a new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society celebrating the centennial with more than 100 photos, posters and ephemera. (Through March 25, 2018.)

Wyoming, Utah and Washington gave women full voting rights in the late 1800’s, even before statehood! “Western states were eager to increase their populations and giving women the right to vote was a great way to attract them,” quipped Scutts.

In two previous exhibitions, the Society focused on the impact of Dolley Madison and first-wave feminists—Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention. Now “Hotbed” gives visitors an up-close look at Greenwich Village in the early 20th century and the activists who “were completely different in attitude and perspective from the 19th-century ‘grandmas’ who were fighting for the same thing,” says Valery Paley, director of the society’s Center for Women’s History. These activists were young, sexy and ready to take to the streets and break rules.

In two previous exhibitions, the Society focused on the impact of Dolley Madison and first-wave feminists—Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention. Now “Hotbed” gives visitors an up-close look at Greenwich Village in the early 20th century and the activists who “were completely different in attitude and perspective from the 19th-century ‘grandmas’ who were fighting for the same thing,” says Valery Paley, director of the society’s Center for Women’s History. These activists were young, sexy and ready to take to the streets and break rules.

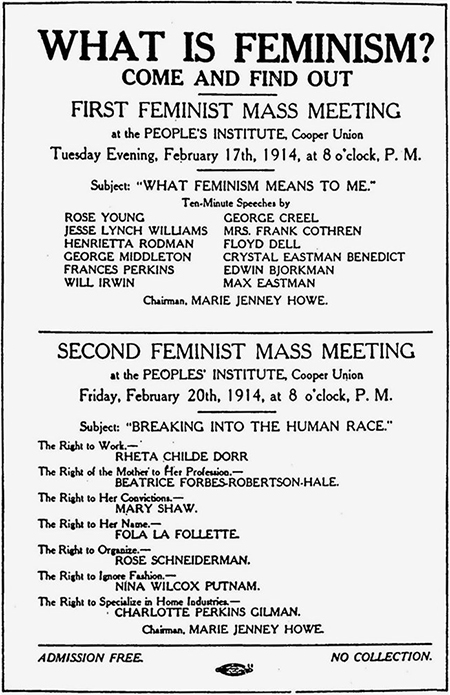

Upon entering the exhibit, visitors are immersed in Greenwich Village’s radical scene. At its center was heiress Mabel Dodge, giving “evenings of art and interest” at her Fifth Avenue apartment, weekly salons for the city’s “movers and shakers” and, Dodge might have added, marchers and partiers. Among these free thinkers were the anarchist Emma Goldman, the nurse Margaret Sanger, who coined the term “birth control” in 1914, and Max Eastman, editor of The Masses. That same year, poet Mina Loy wrote the Feminist Manifesto and activists gathered at Cooper Union for the first mass meeting of “What Is Feminism?”

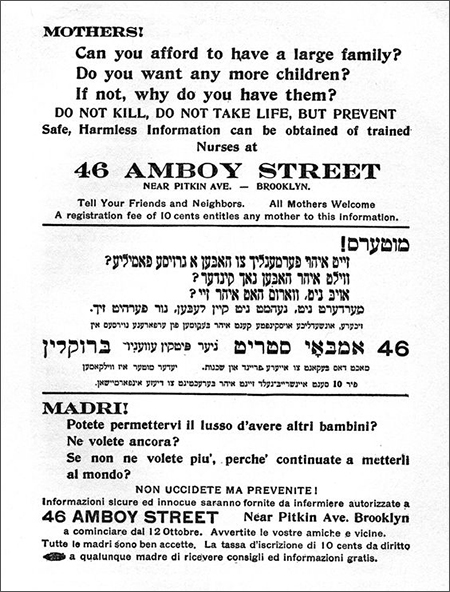

These women were tackling the same pressing issues that are in today’s headlines, said Sarah Gordon: free speech, control of women’s bodies, the right of unions to organize, and racism. Margaret Sanger, a nurse who witnessed the life-threatening problems of women forced to bear too many children, opened the first clinic giving working women access to birth control, when just mentioning birth control was a crime. (“Mothers! Can you afford to have a large family?” asks one poster.)

These women were tackling the same pressing issues that are in today’s headlines, said Sarah Gordon: free speech, control of women’s bodies, the right of unions to organize, and racism. Margaret Sanger, a nurse who witnessed the life-threatening problems of women forced to bear too many children, opened the first clinic giving working women access to birth control, when just mentioning birth control was a crime. (“Mothers! Can you afford to have a large family?” asks one poster.)

The suffragists’ campaign was part of a larger movement effecting radical change and, as the curators show us with an interactive map, middle-class Greenwich Village was ideally located for diverse populations to interact, bordered by the Lower East Side, with its enclaves of Italians, Irish and Jews. Blacks lived here too, in “Little Africa” on Minetta Lane.

The suffragettes, as they were called, co-opted tactics from other groups pushing for their own causes. In preparation for the record-breaking suffrage parade of 1915 (estimates ran from 24,629 to 60,000) they took the idea of using sheet music from union marchers, the use of pageantry from peace parades against the Great War (later known as World War I), and the ins-and-outs of picketing from workers who struck after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Perhaps most haunting is the photo of the NAACP’s silent march down Fifth Avenue protesting lynchings in East St. Louis. “These were all new ideas to middle class white women,” Scutts noted.

July 28, 1917: NAACP’s Silent Parade down Fifth Avenue, protesting lynchings during the East St. Louis riots.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Provocative, sexy, youthful, they dove in and had fun. Suffrage paraphernalia—sashes, banners, fans and pennants—festoon the reproduction of a horse-driven wagon. Close by, a photo of an attractive young New York woman with devil-may care, peering over her shoulder; on her bare back, in capital letters: “VOTES FOR WOMEN.” This printed in a Kansas newspaper.

Like women of today, they were eager to engage in new technologies. Barnstorming—buzzing airplanes over recently built airfields—was the attraction of the day, and a photo shows elegantly dressed women standing in front of a bi-plane, with a banner “Women Want Liberty Too.” The (female) pilots’ plan: take off from MacArthur airfield and scatter Long Island with flyers, advocating for the right to vote.

Using the social media of the time, artists created postcards and posters poking fun at men who didn’t support the movement: One shows a frazzled man doing household chores, saying “I want to vote but my wife won’t let me.” Not to be outdone, homemakers showed their spirit with pepper shakers promising “I’ll make it hot for you.”

While women did ultimately get the vote, the coalition did not hold. “Suffrage in 1920 doesn’t happen in a triumphal way,” said Scutts. As the war continued, some women advocated peace, while others pushed back with the pro-war song: “Wake Up America, Support the War.”

Immigrants were viewed with suspicion: Lithuanian-born Emma Goldman was arrested during a raid on the International Workers of the World Union and deported in 1919. The big question, then as now: Who is and isn’t American? Similarly, lobbyists sought to control who could vote: “In New York, the biggest lobby against the women’s vote was the German beer industry,” said Scutts. The brewers worried that women, many of whom were members of the Temperance Society, would cut into their profits.

Rather than linger on this confusion, the exhibition closes on an up note, with a huge wall photo of the most recent Women’s March, following the inauguration of Donald Trump. Globally, an estimated five million participated, including some 500,000 in Washington, playfully—and proudly—wearing their “pussy hats.” The march for the rights of all Americans continues.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

WE RISE

“We Rise” is the heart-stirring documentary made specifically for the exhibition and shown regularly in the Society’s auditorium. Produced by Donna Lawrence, with music by Alicia Keys (“We Are Here”) and narrated by Meryl Streep, in seventeen minutes it profiles some of the women who were at the center of political thought and action in the early 20th century: Addie Hunton, leader of black women’s organizations; Clara Lemlich, organizer of the shirtwaist workers strike in 1909; Margaret Sanger, physician who advocated for abortions and live-saving operations for women; Lillian Wald, nurse and founder of Henry Street Settlement, and Clara Driscoll, head of Tiffany Studios’ women’s glass cutting department. Each in her own way opened new paths to citizenship, following the lead of the most famous of all female New Yorkers—the Statue of Liberty.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including the Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the magazine. She has co-authored many books including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

You may enjoy other NYCitywoman articles by Suzanne Charlé:

The Notorious Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Trump’s EPA Will Make You Sick

Center for Women’s History Opens in NYC

Clive Davis and the Soundtrack of Our Lives

New York at Its Core: An Arresting Exhibit

December 1st, 2017 at 6:14 pm

Terrific article! I can’t wait to see the exhibit. Well, they got the vote, so that bodes well for us to get what we need today.