ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Turning Antique Lace into Silver and Gold

It’s almost alchemy. Monika Knutsson transforms antique lace into featherweight gold and silver jewelry with a 21st century vibe.

By Linda Dyett

Silvered and gilded: Monika Knutsson with, left, antiqued sterling silver cuff, its lace ’30s Calais; and right, 24k yellow gold, sterling silver and oxidized silver cuff containing a white pearl, its lace ’60s circular Guipure.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Just about anyone around in 1958 will recall the Big Bopper’s raucous rendition of Chantilly Lace. Imagine! All that hullabaloo surrounding a species of 17th century bobbin lace from a sleepy provincial town in France. But as the Big Bopper informs us, it’s got a come-hither, peek-a-boo seductiveness too.

These seemingly contradictory qualities of lace come together and acquire a 21st century vitality in an ingeniously crafted species of jewelry I recently discovered: Real antique lace that’s cut, shaped and repeatedly immersed in pools of liquified gold and silver—only to emerge transformed, in an alchemy-like process, into solid but featherweight gold or silver that sidesteps traditional hammering, welding and chasing, yet produces filigree-like results with intricacies so tiny that even miniscule stitches and micro-millimeter curves show up. The jewelry made from this liquid metal may be nostalgic, but it also has a timely aplomb, an audacity, a chutzpah that makes it a perfect accessory for the emerging cadre of contemporary take-no-prisoners power women of all ages.

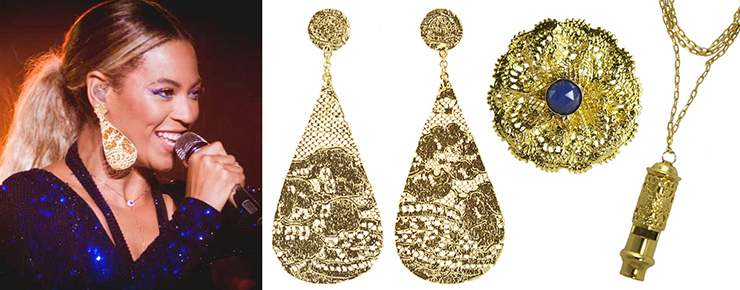

Having discovered electroformed jewelry, I became curious about what kind of person makes a livelihood out of lace that’s saturated in pools of silver or gold. At least a handful of crafters are doing so. But only one I’ve discovered excels in it—the Swedish-born, New York-based artisan-entrepreneur Monika Knuttson, who began offering her Gilded Lace collection seven years ago and has attracted a slew of notables—including that epitome of tough-girl femininity, Beyoncé, who owns and has even performed in it. (Beyonce’s mother owns some of this lace jewelry too.)

Beyoncé, on stage, wearing large, ethereal 24k gold teardrop earrings (also shown alongside) made from ’20s Calais lace used in brasseries. Further right: 24k gold cocktail ring with blue rose chalcedony stone, made from ’20s Valenciennes lingerie lace. Far right: long, dangling 24k gold whistle necklace repurposed from a London police whistle and ’20s French bobbin lace.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A transplant from the city of Jonkoping, in a province of Sweden known for its entrepreneurial spirit (IKEA’s founder, Ingvar Kamprad, is also from that region), Knutsson grew up devouring fashion magazines, making her own clothes and treasuring the handmade lace collection she inherited from her grandmother. Attending university, she studied international business and marketing, leading to the start of a career in ship brokering. Soon afterwards, she met an American—Bruce Kogut, a professor at the Wharton School of Business in Philadelphia. In 1984 the two married and moved to Philadelphia. While working there as a medical market researcher, Knutsson took an evening class at the Moore College of Art & Design. Designing came so easily to her that she began thinking of switching to a fashion career.

Fast forward to 1999. Knutsson, Kogut and their teenage son and daughter moved to Paris, where he began a teaching appointment at the Ecole Polytechnique and she continued taking courses—this time at ESMOD, the legendary fashion school. “A super job” with the designer Isabel Marant followed. There Knutsson designed jewelry and “learned to be organized and goal-driven.”

Guipure lace from Knutsson’s Vintage Circle Collection of iconic, Mod-influenced ’60s French and ’70s American lace. Left: large 24k yellow gold, rose gold, sterling silver and antiqued silver chandelier drop earrings; the lace is ’70s American. To its right: sterling silver necklace with blue geode bead, made from ’60s American lace. Further right: gold stud earrings, again, ’60s American. Far right: Large sterling silver cuff—’70s American.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

It was also at Marant that she met an artisan who encased fabric in metal for runway displays. That intrigued her. Why not do the same with antique lace, she reasoned—as a way of preserving and celebrating this precious fabric that otherwise will likely shred and disintegrate? With that in mind, she began buying precious heirloom lace at flea markets, estate sales and antique shops.

In 2008, Knutsson and family relocated to New York, where Kogut became the Sanford Bernstein Chaired Professor at Columbia Business School, and she scoured the electroforming industry, finally finding a small factory—in Greenpoint, Brooklyn—that agreed to do her gilding and silvering.

In 2010, converting a spare room in the Knutsson-Kogut Upper West Side apartment into a work studio, she embarked on her maverick jewelry-making enterprise. First she studies each piece of lace (typically made of cotton) to discern its pattern. Then, with a full-time assistant, she cuts and constructs “almost like making a 3D garment.” If the item being made is small, she isolates and clips out single sections or motifs—blossom … leaf … bow. If it’s a necklace or cuff, she selects larger sections or connects multiples of the same motif. Certain earrings and cuffs then get metal wires sewn to their underside, for strength and flexibility. For cuffs, Knutsson also attaches ribbon to create a smooth edge.

From the Shimmering Solstice Collection: Left: sterling silver cuff-bracelet with dangling chain and leather ribbon closure; its lace is ’50s American, used for bed linens and home décor. Center: 24k gold necklace with back chain; its ’30s Calais lace was used for lingerie. Right: antiqued sterling silver fan-shaped pendant necklace, whose ’20s Calais lace showed up in brasseries.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Sometimes she finds herself with only a small piece of precious lace that yields just one jewelry item. More likely, she’ll have enough of each piece to produce, say, 10 or 12 bracelets. And occasionally, she’s able to fill a large order for the same design. She once turned a piece of 1920’s Calais lace into 53 cuff bracelets for Arhaus, the home design and jewelry retailer.

Next, the all-important trips, several times a week, to the Greenpoint electroforming factory. (Concerned with copy-catting, Knutsson won’t reveal its name.) This plant is an early 20th century holdover that got its start gilding baby shoes and lately has not only covered NASA instruments with 24k gold (so they won’t deform as they approach the sun), but also gilds the Oscars. The process? Several two-day submersions in an electrically charged bath containing minuscule 18k or 24k gold, rose gold, sterling silver or occasionally gunmetal granules that adhere to the jewelry. After each dipping, Knutsson, a self-described “nitpicker,” or her assistant (also evidently a nitpicker) is on hand, eagle-eyed and at the ready, to smooth out any spikes and do filing and sandpapering before the next immersion.

Back at her studio, she embellishes some items with gemstones and threads grosgrain or leather ribbon through the eyelets of others. Most, however, are left as is: tributes to the beauty and intricacies of lacemaking. “I let the lace speak for itself. I love the ethereal play of light shining through—that’s very Scandinavian,” Knutsson comments.

Knutsson assisting a visiting San Francisco client, trying on sterling silver earrings made from ’20s German spider web bobbin lace.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

She also does a brisk trade in custom bridal jewelry—transforming pieces of lace from the wedding gown worn by the bride’s mother or grandmother into earrings, bracelets, necklaces and headpieces. She’s also been turning lace into home decor items such as lampshades and room-divider screens, through which light naturally passes. A recent alcove screen, made on commission, is composed of lace ribbons, which she sewed together to create a pattern. The light shining through the screen is breathtaking. Each item is given a name and number—based on the piece of lace from which it emerged—and is sold with a hangtag description of its origin.

Over the years, Knutsson has become a lace history expert, versed in the origin and lore of each style. She has a love for homemade Swedish and American crochet lace, the latter used as edging for bloomers, bed linen and shelf trim. “When the pillowcase or garment wore out, the women used to cut off the lace and re-use it,” she explains. “So the pieces that I’m able to find may be yellow and stained, but they are still beautiful.” She also speaks in awe of the pulled thread designs of the Cuban needle worker Carmen Fiol, whose work Knutsson will soon showcase. But her favorites—the ones she’s likeliest to use—are the French varieties: scalloped Calais lace from the 1920s and ’30s—whose stylized flowers and arches sewn in thick, embroidered thread have a mesmerizing 3D effect; Deco-influenced Puy-en-Velay bobbin lace from the ’20s –’40s; and French ’60s honeycomb lace, whose asymmetric geometrics reflect that period’s Mod design influences.

Left, a Philadelphia collector, wearing 24-karat gold-dipped bracelet made from ’30s French Calais lace, and 24k earrings, from ’50s American Raschel lace. Right, a client from British Columbia wearing a matching gold cuff and earrings whose bobbin lace is ’20s French Puy-en-Velay. The earrings were custom-made.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Obsessive in every detail of jewelry-making, Knutsson is also a born fashion marketer. She presents two collections per year, each highlighting a unique type of design: lace influenced by Berlin’s iron jewelry in the ’20s; Stockholm lace from the ’40s—“the Ingrid Bergman era;” French and American circular lace from the ’60s and ’70s.

Her work raises questions about the nature and limits of jewelry and what it means to be a jeweler. No doubt Knutsson is as zealous as any filigree-maker, approaching her craft almost as a ritual. But is she a jeweler or a re-purposer? Or more likely, distinctions like these don’t matter. This is one jeweler who’s pushing limits and opening up new artisanal terrain. And all this because Knutsson created a unique opportunity that appealed to her fashion sensibility, her love of lace and her entrepreneurial skills.

The owners and salespeople at the shops selling her jewelry report that it inspires numerous questions from customers—who represent a wide age spread, from the twenties through the seventies. And Knutsson herself points out that her gilded and silvered lace brings joy. “I love spreading happiness like that,” she declares. Maybe not Big Bopper happiness … but not entirely removed from it, either..

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Where to Buy It?

Monika Knutsson’s entire Gilded Lace collection is available by appointment and online at monikaknutsson.com, while her American lace is also sold at Amazon’s Martha Stewart American Made section.

Prices: $195 to $1,200 for readymade items; more for custom-made pieces—especially those with gemstones such as rubies, sapphires and diamonds. Through Thanksgiving week, Knutsson is holding a rare 35% – 60% sale of one-of-a-kind and remnant Guipure, eyelet, Puy-en-Velay, and near-ethereal embroidered net pieces. They’re viewable in the Shop Now tab of her website. Twenty percent of each sale will go to the New York branch of the Children’s Aid Society.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Linda Dyett’s articles on fashion, beauty, health, home design, and architecture have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Monocle, Afar, New York magazine, Allure, Travel & Leisure, and many other publications.

You may enjoy other NYCitywoman articles by Linda Dyett:

Tips from a Top NYC Hair Colorist

A Makeup Update for Mature Faces

A Look at Five Visionary Studio Jewelers

Five More Visionary Studio Jewelers