ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

A Look at Five Visionary Studio Jewelers

Their inspirations here in fast-paced NY, like their challenges, are non-stop and numerous. Their stock in trade? Non-stop beguiling.

By Linda Dyett

Blown glass and sterling silver necklace by Biba Schutz.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

“Jewelry is a seduction,” proposes the New York metalsmith Deborah Aguado. If so, it’s one of those take-no-prisoners seductions, captivating its crafters as well as those who wear it.

It’s a sign of the times that a remarkable number of today’s artisan jewelers are women. And while the new generation tends to be market-oriented, it’s their elders, who came of age in the later years of the studio movement that got under way in the 1940s, who have changed the course of this decorative art form, stretching the limits of its aesthetics, techniques and materials. Circa 2019, their modernity has yet to be supplanted.

Happily, many of these pre-boomer and boomer jewelers are still at it, plying their trade, like Aguado and the four others profiled below, here in New York City. Which is no easy feat. This is a town that values fine art and fashion. Crafts? Not so much. Studio jewelers (craftspeople who design and make one-of-a-kind pieces and also do limited production in their own workplaces) have long been outliers here, with affordable work space hard to come by and a scarcity of galleries selling their work. Even the Diamond District gemstone and tool suppliers are a dwindling breed today.

Yet each of the jewelers in this article is energized in one way or another by this multifarious, glittering, shimmering, get-it-done-yesterday city. Just a word of warning: Studio jewelry like theirs is highly addictive. Once it caresses your clothing or skin, you’ll find it tough—even impossible—returning to impersonal mass market jewelry sold in stores. (Fortunately, their prices are commensurate.)

For starters, here’s a news flash: The Museum of Arts and Design’s annual LOOT: MAD About Jewelry event, featuring working artisans from many countries, is usually held in April and everything is for sale. For aficionados, this show is not to be missed.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

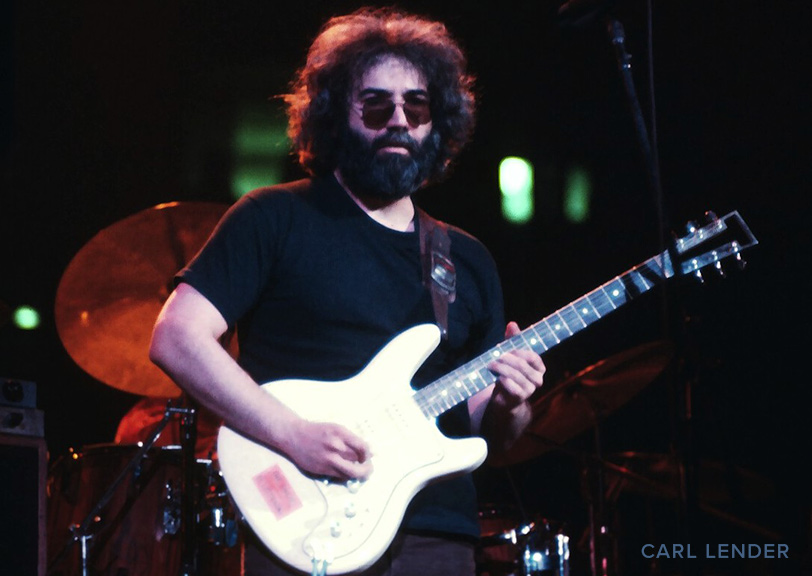

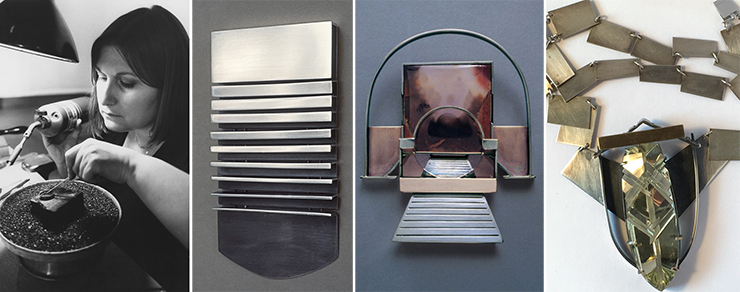

Deborah Aguado: Probing the Limits

No flowers, no jewelry-as-mere-adornment for Deborah Aguado. “For me, it’s architecture for the body,” she explains. And while her focus is on the subtle interactions of precious metals and gemstones, she also knows how to create jewelry that compliments the wearer. There’s the sterling silver brooch in her “Louvre” collection, for instance, displaying rows of hinged vertical bars that caress and undulate with the body. Other pieces, meanwhile, are tale-spinning narratives. Like her Night Train series depicting trapezoidal train tracks. They’re virtuoso tableaux of travel and perspective framed in precious metals and gemstones.

Raised in the Bronx, Aguado started out as an assistant in the garment industry. But strolling the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit on Sundays, she became fascinated by the wire jewelry displayed on the bridge tables lining Sixth Avenue. “I wanted to do that too,” recalls this daughter of an iron worker who survived the Russian Revolution. Aguado made the break in the early ’60s, studying at the Tyler School of Art and then traveling the world, researching indigenous and contemporary crafts—notably in Peru, Japan, Turkey, and Western Europe. Today, her jewelry is in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian, among many other museums.

Despite her extensive travels, Aguado has always returned to New York, her base—a nurturing source for her creativity that she’s extended to others. In 1973, she created a jewelry department at Sarah Lawrence College and in 1974 a crafts program at the New School. The urban landscape inspires her as well; she finds inspiration in the city’s terra firma—even the ground cover in Central Park. There one spring shortly after a death in her family, she collected tree bark, twigs and acorn caps to embed like precious gemstones in a series of silver-framed brooches that are meditations on time, nature, and mortality.

Aguado’s jewelry is sold at the Aaron Faber Gallery in Midtown and through her website. deborahaguado.com. $200-20,000.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Cara Croninger: “One Word—Plastics”

She’s a pioneer—some say the pioneer—of bangles, beads and brooches made of plastic resins—polyester (for colors) and acrylic (for transparency). Looking like no previous jewelry, Cara Croninger’s clunky, organic, ethnic-oriented sculptures-as-baubles emerged out of the in-your-face esthetic of the Pop Art era. But they’ve stood the test of time as haunting modern-day amulets. Not only do they create bolts of vivid color never possible with enameling or polyester resin’s predecessor, Bakelite. But we respond on a visceral, intuitive level to Croninger’s touchable textures with the dawning apprehension that she’s turned commonplace plastics into precious, luminous jewels.

Croninger grew up on her family’s hardscrabble Michigan dairy farm, where almost everything was made by hand. Then came sculpture studies in Chicago and a late ’60s move to New York. Hand-stitching leather goods for East Village boutiques, she was drawn to Downtown’s early ’70s explosion of jewelry. By then a single mother of two, she embarked on jewelry-making herself, choosing plastics for their production potential. But the molding, slicing, grinding, polishing, color-mixing, carving and chiseling so intrigued her that she continued making one-of-a-kinds. “Provoked,” as well, she says, by New York’s multi-ethnicity and the non-Western art in the city’s museums, Croninger became an early art jeweler, who helped found Artwear, the influential Soho jewelry gallery run by impresario Robert Lee Morris. It didn’t take long for her pieces to appear on the cover of Vogue. Today they’re in museum collections and are still sought out by style individualists.

Croninger grew up on her family’s hardscrabble Michigan dairy farm, where almost everything was made by hand. Then came sculpture studies in Chicago and a late ’60s move to New York. Hand-stitching leather goods for East Village boutiques, she was drawn to Downtown’s early ’70s explosion of jewelry. By then a single mother of two, she embarked on jewelry-making herself, choosing plastics for their production potential. But the molding, slicing, grinding, polishing, color-mixing, carving and chiseling so intrigued her that she continued making one-of-a-kinds. “Provoked,” as well, she says, by New York’s multi-ethnicity and the non-Western art in the city’s museums, Croninger became an early art jeweler, who helped found Artwear, the influential Soho jewelry gallery run by impresario Robert Lee Morris. It didn’t take long for her pieces to appear on the cover of Vogue. Today they’re in museum collections and are still sought out by style individualists.

In 2007, Croninger moved from her Dumbo work studio to the Garnerville Arts & Industrial Centers, located in a pre-Civil War factory complex in the lower Hudson Valley. There she’s focused on items made from leftover chips and chunks. Musing today on her lifelong avoidance of gemstones or gold, she maintains that “intrinsic value is in the way you respect and manipulate your material.” However, one of her dealers, the avant garde If emporium, on Grand Street, recently persuaded her to produce small-scale silver earrings.

Cara Croninger passed away in March 2019. Check 1st Dibs and Ebay for jewelry sales.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Judith Glassman: Hooked!

“Oh, how stunning,” exclaim passersby when they spot the beaded, satin-corded, crocheted and knitted necklaces and bracelets Judith Glassman invariably wears. “Did you make that? Can you make me one too?” Yes, responds this self-taught jeweler, adroitly fishing out her business card. Her focus is on rich and subtle color combinations, which she obtains in two very different ways. In one, she combines beads and gemstones—boulder opal, agate, turquoise, matte lapis, anything Swarovski, Venetian and cane glass (like the ovals with cream and brown swirls, which Glassman’s dubbed hot fudge sundaes), et al. These she turns into lariats, donut pendants, single strand necklaces, and other classics that are favored by pre-boomers and boomers. And then there are her fiber items made of brightly colored yarn: retro-style crisp cotton crocheted and knitted pieces, currently sought out by nostalgia-minded Millennials. Though a relative newcomer to jewelry sales, Glassman is on to something here.

She tells of a pivotal moment, growing up in Bayside, when she added orange trim to a brown dress she’d just Crayola’ed in a paper-doll coloring book. “What magic! I hadn’t known those two colors could be combined,” she recalls. In the early ’70s, armed with an English degree from Queens College, she wrote a series of craft books, starting with The New York Guide to Craft Supplies, while making seed-bead necklaces in her spare time. Then in the ’80s, an about-face: she dove into the burgeoning cyber world, starting a new career training computer users. But by the 20-aughts, missing artisanal goods, she resumed necklace-making—first for herself, then for friends, friends of friends, and those strangers on the street. Gradually jewelry became Glassman’s focus, conducted at a space-hogging table in her Upper West Side living room.

She tells of a pivotal moment, growing up in Bayside, when she added orange trim to a brown dress she’d just Crayola’ed in a paper-doll coloring book. “What magic! I hadn’t known those two colors could be combined,” she recalls. In the early ’70s, armed with an English degree from Queens College, she wrote a series of craft books, starting with The New York Guide to Craft Supplies, while making seed-bead necklaces in her spare time. Then in the ’80s, an about-face: she dove into the burgeoning cyber world, starting a new career training computer users. But by the 20-aughts, missing artisanal goods, she resumed necklace-making—first for herself, then for friends, friends of friends, and those strangers on the street. Gradually jewelry became Glassman’s focus, conducted at a space-hogging table in her Upper West Side living room.

For her, New York’s beating heart is still the Midtown Jewelry District, even with its dwindling numbers of suppliers. Rather than shop online, she takes delight in buying supplies in-person there, swooning not only over the beckoning gemstones, but even the findings—the magnetic clasps, bezels, et al.

Glassman’s jewelry is sold on her website, judithglassman.com. She makes house calls too. $25-2,500.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Patricia Madeja: No Stone Unturned

That traditional staple, the strand of pearls, is given a contemporary spin by Patricia Madeja. Rather than string them, she floats her pearls, as well as the translucent quartz, beryl and diamonds she favors, inside carefully engineered cubes and cages, freeing up their three-dimensionality, giving them room to move. Then she turns them into neckpieces, bracelets and earrings via sterling and gold connecting links she fabricates herself. Imagine an uninterrupted flow of shimmery kinetics, shivering like tambourines and slithering like Slinkies along the body’s contours. That’s Madeja’s forte. “Craftsmanship and function are of the utmost importance to me, she says.

As a child attending a carnival in her native Philadelphia, she won a pendant containing a red plastic bead in a faux gold cage. It fascinated her and very possibly propelled her towards a jewelry degree at Pratt Institute, followed by a four-year, late ’80s stint with Robert Lee Morris. In 1989 Madeja moved to West Islip, her life partner’s home town, where she acquired a sizable sun-filled studio. And then in ’98, Pratt invited her to redevelop its moribund jewelry program. She agreed, and is now a professor there.

Spending much of her work week at Pratt, in Brooklyn, Madeja takes frequent detours to Manhattan, which she finds “incredibly stimulating, with the museums, the jewelers, the gemstone dealers.” She also makes use of her Long Island Railroad commute for developing new ideas, telling of a set of costly and unusual lemon citrines she’d bought on impulse that sat forlornly on her work table for a year. It was while sketching on the train one day that she suddenly came up with idea of freely spinning gems inside geometric frames—which led to “a whole new design language.”

Madaja’s designs are sold at the Smithsonian’s Craft and Craft2Wear shows, the Philadelphia Museum of Art Fine Craft Show, the American Craft Council Show in Baltimore and via her website. patriciamadeja.com. $200-20,000.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Biba Schutz: Space Explorations

“I make objects for the body,” says Biba Schutz, studiously avoiding the word jewelry. Looking nothing like conventional necklaces, bracelets, and earrings, hers have a floaty fluidity. No fronts, backs or sides—even the clasps are integrated into her designs. “Nothing is solid. You could travel through my pieces,” she suggests. And though it all looks spontaneous, every item is carefully calibrated—a result, Schutz explains, of her studying that exacting discipline, graphic design, as an American University undergraduate. Her materials? The primary ones: sterling, gold, bronze, and copper wire, strips and threads; bits of glass and mica; raw-cut stones (including diamonds) leather; antler horn (naturally shed). Avoiding shiny surfaces, she gives everything a roughened, light-absorbing texture—forging drilling, soldering, and hammering by hand: lately, she’s even learned glass-blowing. What emerges—most notably Schutz’s signature bird’s-nest-esque wrapped wire pieces—is surprisingly delicate.

Her birth was commemorated with a gold charm bracelet—a piece of family lore which would become a talisman for her career. Growing up in Laurelton, Schutz watched her restaurant contractor father develop floor plans at his home drawing table. So even early on, she was learning the rhythms of the creative process. After finishing college, she made hair ornaments, selling them at accessories and jewelry shows. By 1986, gravitating to self-taught jewelry-making, she began fulfilling her charm-bracelet birthright—though her designs are utterly contemporary, suitable for wearing with today’s restrained, minimalist clothing.

“Urban living is paramount for me,” Schutz says, the gritty city a continual inspiration. Strolling from her home in Stuyvesant Town to her studio in the now-nearly-extinct fur district in the lower West 30s, she takes in the street action, the tough romance of concrete and glass, the spaces between buildings. A favorite is the Flatiron—whose jagged freestanding presence in space fascinates her.

Schutz’s jewelry: in the permanent collection of many museums, is sold by appointment at her studio and at Gallery Loupe in Montclair NJ, Jewelerswerk in Washington, DC, and Sienna Patti Contemporary in Lenox MA, which shows at the Collective Design Fair, held in New York every May. bibaschutz.com. $350-8,000.

Also see Five More Visionary Studio Jewelers, part 2 in this series by Linda Dyett.

Linda Dyett’s articles on fashion, beauty, health, home design, and architecture have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Monocle, Afar, New York magazine, Allure, Travel & Leisure, and many other publications.