ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

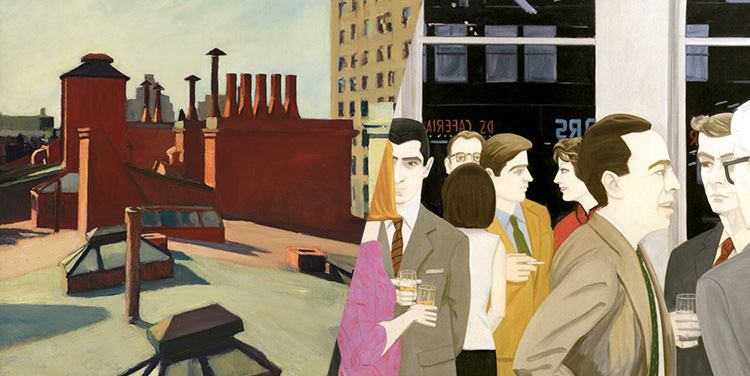

Two Artists’ Eyes on New York

Edward Hopper at the Whitney, Alex Katz at the Guggenheim

By Suzanne Charlé

February 4, 2023

Bucking artistic trends of their day, two of New York’s most celebrated artists, Edward Hopper and Alex Katz, focused on the city and its denizens. The results, as fascinating as they are divergent, give us viewers multiple ways of seeing the city—and ourselves.

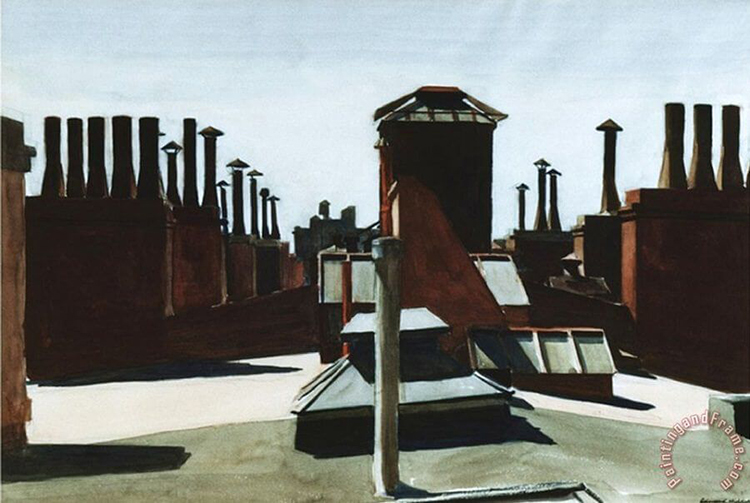

New York on a sunny day is a visual pleasure: the warm glow of brick row houses; the intriguing geometries of chimneys and water tanks atop roofs—even on some of the West Side’s most elegant buildings. These and others sights are at the heart of New York, as much as, perhaps more than the Empire State Building.

Edward Hopper, Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Oil on canvas, 35 3/16 × 60 1/4 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.426 © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Certainly that was what Edward Hopper thought—and painted, giving “narrative authority to the common structures and out-of-the-way corners he passed, rather to the iconic buildings,” as Kim Conaty, co-curator of the Whitney Museum’s exhibition Edward Hopper’s New York, writes. (The exhibition runs through March 5.)

As a child, he visited the city from Nyack with his family, and after graduating from school he moved here in 1908, first working as a commercial illustrator. He relocated several times before settling into the top floor of 3 Washington Square North, a three-and-a-half story brick-and-stone Greek Revival built in 1833. For nearly 60 years, during a time of intense urbanization, Hopper wandered all over town, with the eyes of an explorer. “I get most of my pleasure out of the city,” he told a reporter.

Despite the intense urbanization going on, Hopper’s interest, his vision, was in the horizontal city—not the vertical. Over two decades, he returned to depict the Queensborough and Williamsburg Bridges, and views from them.

Edward Hopper, From Williamsburg Bridge, 1928. Oil on canvas, 29 3/8 × 43 3/4 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; George A. Hearn Fund, 1937. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy Art Resource, New York

Edward Hopper, Manhattan Bridge, 1925–26. Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper, 13 15/16 x 19 15/16 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1098

He roamed the East River, recording the boats and Roosevelt Island (then Blackwell’s Island).

Edward Hopper, Tugboat with Black Smokestack, 1908. Oil on canvas, 20 3/8 × 29 5/16 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1192. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Hopper, Blackwell’s Island, 1928. Oil on canvas, 34 1/2 × 59 1/2 in. Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, AR. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy Art Resource, NY. Photography by Edward C. Robison III

His roof was his vantage point, where he drew and painted his impressions of 19th century buildings, with skylights and steam pipes, and water tanks—and, in the distance, new tall buildings encroaching on them. “Looking was his primary channel of self-knowledge,” as one friend said.

Edward Hopper, Roofs, Washington Square, 1926. Watercolor over charcoal on paper, 13 7/8 × 19 7/8 in. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Beal. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Hopper, My Roof, 1928. Watercolor on paper, 14 × 20 in. Collection of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Family. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Hopper, City Roofs, 1932. Oil on canvas 35 11/16 × 28 11/16 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; bequest of Carol Franc Buck 2022.98

He shunned the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings, the new skyscrapers making so much news. “Edward likes the surface of the earth, he likes to stay close to it,” explained his wife Jo, also a painter. Hopper conceded, “I just never cared for the vertical.”

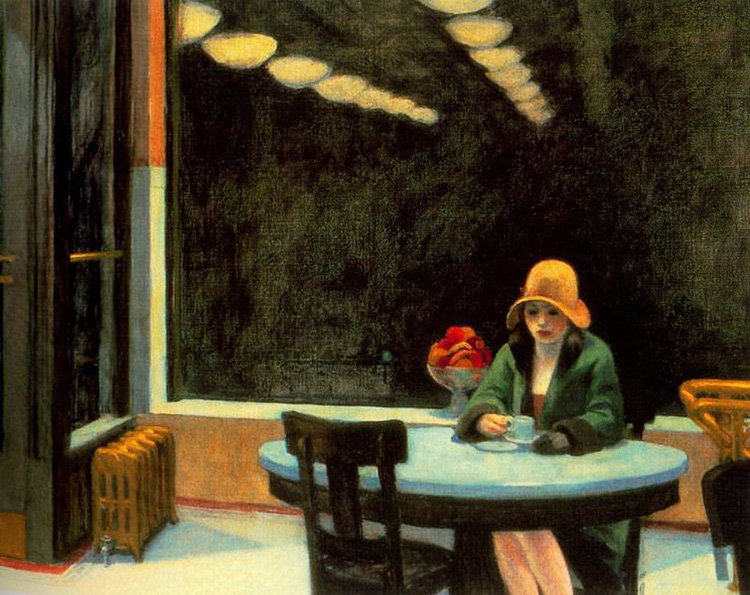

Instead, the streets were his subjects, the exteriors and interiors—the public and private—and the people, often solitary, who occupied them.

Edward Hopper, Automat, 1927. Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 × 35 in. Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa; purchased with funds from the Edmundson Art Foundation, Inc. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Rich Sanders, Des Moines, Iowa

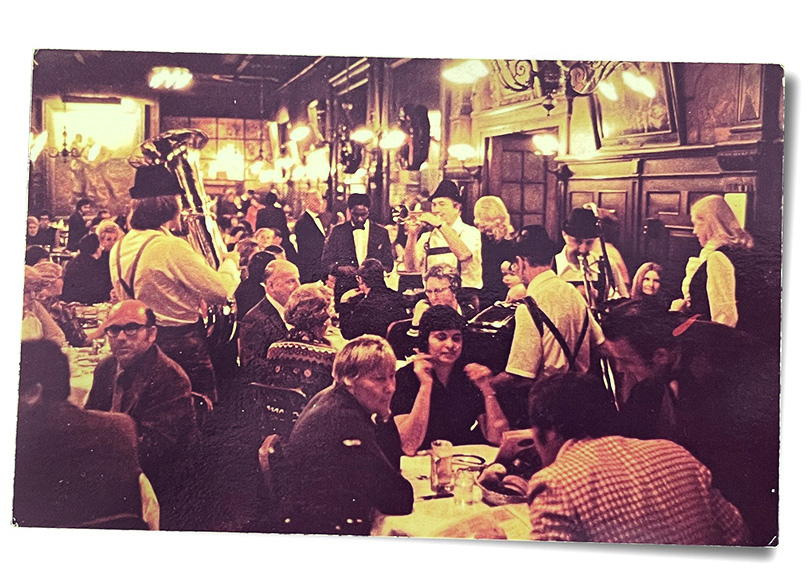

Hopper and his wife enjoyed city life: the restaurants, movies, and particularly theater (they went to over 100 shows between 1925 and 1936—and kept the ticket stubs.)

Edward Hopper, The Sheridan Theatre, 1937. Oil on canvas, 17 × 25 in. Newark Museum of Art, NJ; Felix Fuld Bequest Fund. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy Art Resource

Edward Hopper, New York Movie, 1939. Oil on canvas, 32 1/4 × 40 1/8 in. The Museum of Modern Art; given anonymously. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy Art Resource

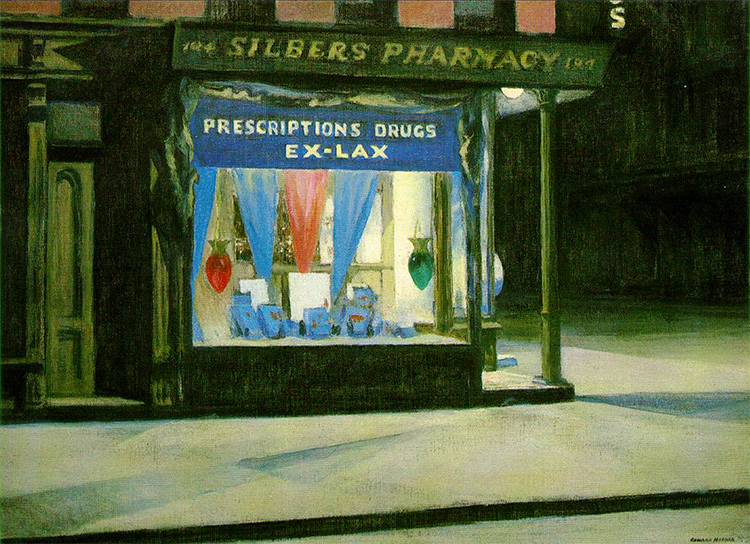

His was a selective realism. “Do you notice how artificial trees look at night? Trees look like theater at night,” Hopper said in 1964. As friend and stage designer Jo Mielziner put it, he “designs with an eraser.”

When Hopper moved to Washington Square, he and many artists in Greenwich Village enjoyed the bohemian and cheap rents. But times changed. Preceding today’s gentrification, NYU had other plans, and tried to evict them in 1946. The Hoppers, like the others, successfully fought them over the years and kept their rental. They lived there until their deaths, Edward in 1967 and Jo ten months later, in 1968. The 200 paintings, 3,000 works of paper (and the ticket stubs) that were still in the apartment were willed to the Whitney Museum.

You can take a tour of the sites in Hopper’s paintings, thanks to a map by the Whitney.

Some locations, like the Sheridan Theatre, no longer exist. Also, bear in mind that Hopper worked more on “improvised” scenarios than “from the fact,” taking elements from one store and adding them with others in the neighborhood—distilling the essence of the experience.

Edward Hopper, Drug Store, 1927. Oil on canvas, 29 × 40 1/8 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; bequest of John T. Spaulding. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Approaching a City: Hopper’s Visions of Urban Space

Wednesday, February 15, 7 pm

Floor 3, Susan and John Hess Family Gallery and Theater

Inspired by Edward Hopper’s New York, this program brings together an interdisciplinary group of artists and writers reflecting on the histories and aesthetics of the urban spaces Hopper engaged with in his work, from the intimacies of private apartments to the public fantasies of the street to the flux of the city itself. Moderated by Kim Conaty, and Steven and Ann Ames, Curator, the conversation features speakers David Hartt, Kirsty Bell, Jane Dickson, and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro.

This program is funded by the Flack Family in memory of longtime Whitney docent Marianne L. Flack.

Tickets are required ($8 adults; $6 members, students, and seniors).

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Alex Katz is another New York artist who focuses his work not so much on the city itself, but on his friends in the city. Until February 20, you can see Alex Katz: Gathering, the Guggenheim’s eight-decade retrospective of his career—thus far. The museum presents a spiraling visual diary of one of the longest and most productive careers in American art. (At age 95, Katz is still working.)

Alex Katz, Gathering, Installation view, photo: Ariel Ione Williams and Midge Wattles © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Paintings range from 1946, when Katz was a 19-year-old student at Cooper Union, to the present, virtually all here in New York and up in Maine, where he has spent every summer since the late 1940s. In his autobiography, he wrote he was mainly interested in “empirical sensations—painting outside the world.”

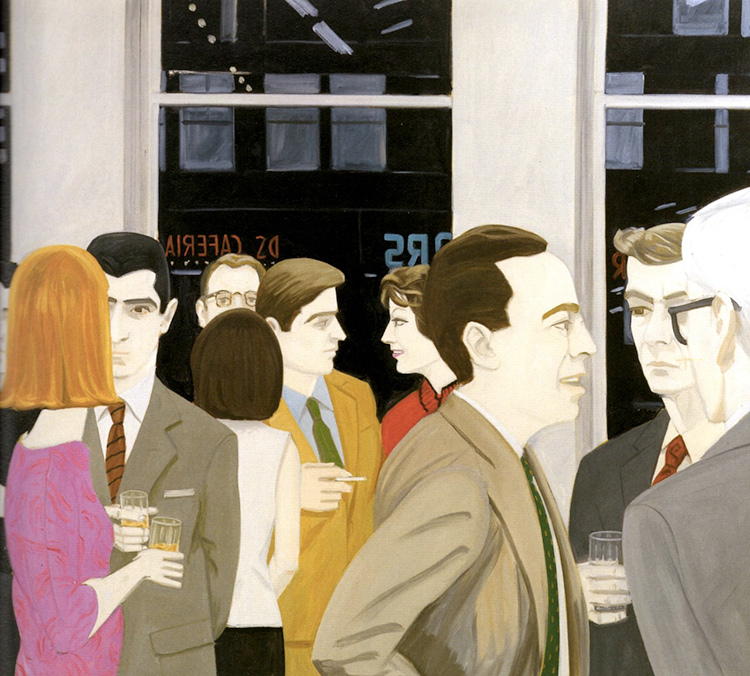

Here are friends on the beach and at a party—stylish figures on flat, muted backgrounds.

Alex Katz, Round Hill, 1977. Oil on linen, 71 × 96 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Barry and Julie Smooke. © 2022 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

Alex Katz, The Cocktail Party, 1965, Oil on canvas. 183 x 244 cm. Private Collection, Chicago. © 2022 Alex Katz/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poet Allen Ginsberg is splintered into six paintings, and dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor performs with his troupe and stands separately, a solitary figure. (Katz designed the sets and costumes for many of Taylor’s performances.)

. Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Throughout, Katz’s wife, Ada Del Moro, is present: her face filling an entire canvas with multiple figures as if Katz was shooting photos of her, and here, her face and figure cut in half.

Alex Katz, Ada With Nose, 1969 (aluminum cut-out)

On some occasions, Alex does head outside, as exemplified by New York at Night, painted in the late 1980s—a dark night in a dark period for the city), and decades later, the glowing Yellow Tree 1, from 2020.

Installation view, New York at Night. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams and Midge Wattles © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Alex Katz, Yellow Tree 1, 2020. Oil on linen, 72 × 72 in. Private Collection, Republic of Korea. © 2022 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

In 1997, he painted Cornice, the cornerstone of a red brick building, with taller buildings rising behind, reminding us that Katz and Hopper walked the same streets, each responding with his own sensibility and creativity.

Alex Katz, Cornice, 1997, Oil on linen, 96 1/2 × 128 1/4 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including The Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the Magazine. She has co-authored many books, including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

For other NYCitywoman articles by Suzanne Charlé, see: