ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

The Paul Taylor Dance Company Returns to Lincoln Center

Michael Novak, artistic director, and his high-energy troupe deliver a nonstop exuberant mix of Paul Taylor classics, along with world premieres by resident choreographers Lauren Lovette and Robert Battle

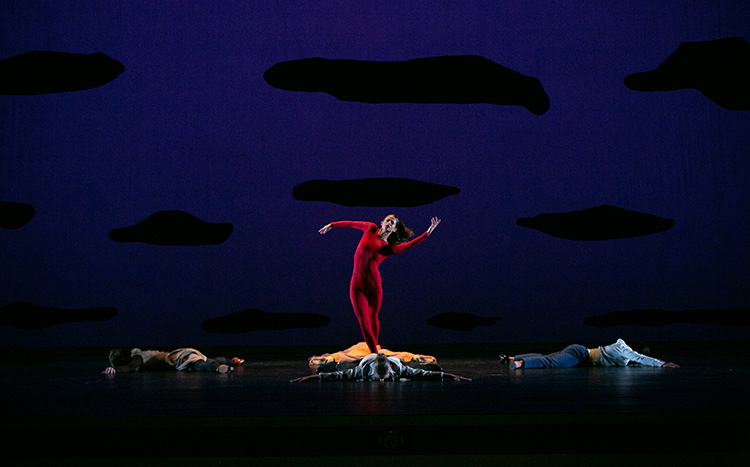

All in red: Maria Ambrose in Scudorama. Photo by Whitney Browne.

October 28, 2025

On November 4, the Paul Taylor Dance Company returns to Lincoln Center for the 13th year, with three weeks of dances by Paul Taylor, world premieres by other choreographers, and live music performed by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s.

Praised by The New York Times as “one of the most exciting, innovative, and delightful dance companies in the entire world,” the troupe was founded by Taylor in 1954, and his creative genius—and his full-bodied physicality—continues to be on display to this day. The current repertoire includes world premieres by resident choreographers Lauren Lovette and Robert Battle, as well as Paul Taylor classics that range from romantic to humorous to controversial.

Here’s a glimpse at this year’s repertoire.

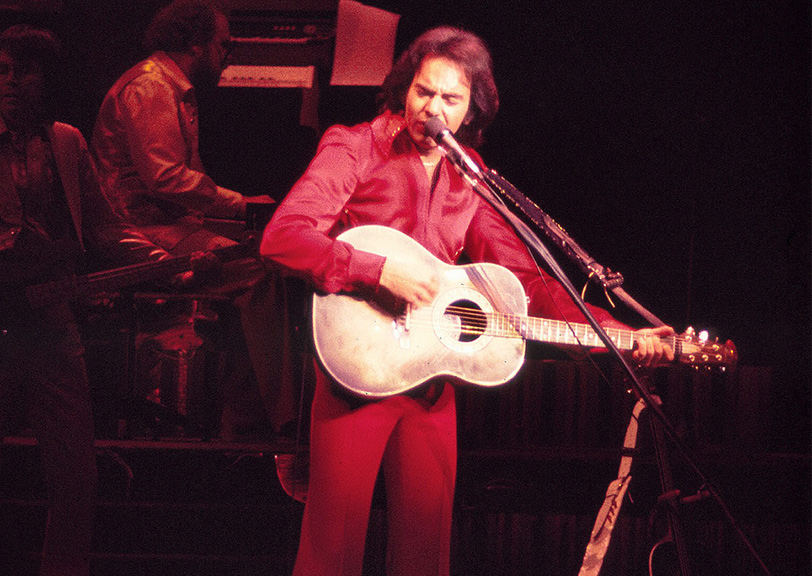

The earliest piece in the season is Scudorama, which Taylor choreographed and danced in 1963, when the United States was still in the grip of nuclear fear following the Cuban Missile Crisis. A “dance of death leavened with light touches,” Taylor wrote about Scudorama, expressing the fraught anxiety of that time.

Balancing act: Michael Trusnovec, Aileen Roehl, and Company in Sunset. Photo by Paul B. Goode.

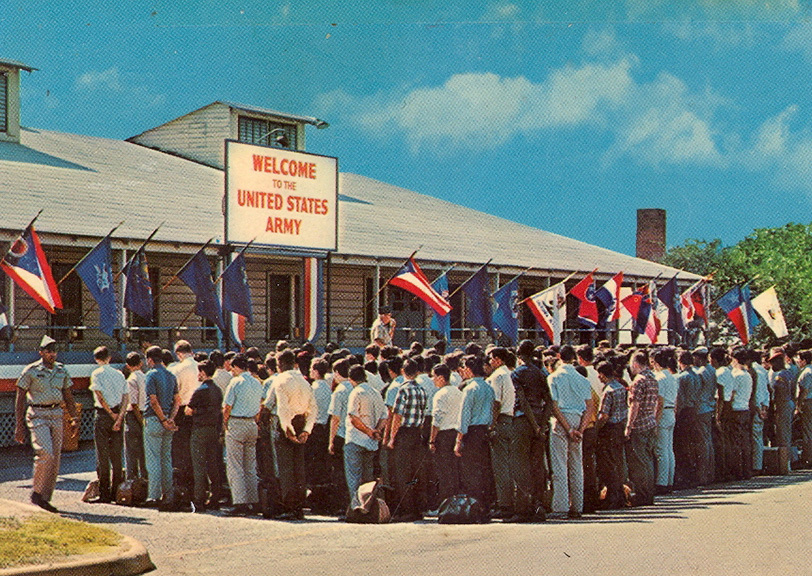

Sunset is a masterwork Taylor created with his good friend the artist Alex Katz. The two collaborated on 16 pieces in the 1960s and 1970s. An antiwar piece, with a huge green scrim that blocks out one third of the stage, Sunset challenged what Taylor and dancers could and couldn’t do, and reflects the sense of loss when people leave in wartime.

Engaging with an outsize cabbage: Eran Bugge and Company in Diggity. Photo by Paul B. Goode.

Diggity, meanwhile—with metal cutout dogs (beige and white like Taylor’s two real dogs)—created an obstacle course for dancers. Cathy McCann, the current rehearsal director, notes that in each of these “experimental art works, a dancer needs to be both athlete and artist.” A member of the troupe for 13 years, McCann performed in both Sunset and Diggity.

Forward March: Jada Pearman, Devon Louis, and Company in Esplanade. Photo by Steven Pisano.

One of Taylor’s most significant works, and certainly the most New York–centric, is Esplanade, which he devised in 1975. “Paul saw a woman running for a bus and created the dance using a limited vocabulary,” McCann recalls. One of Taylor’s most celebrated works, Esplanade is set to two Bach violin concertos and involves nontraditional dance movements—running, walking, sliding, standing, falling. “A masterwork showing how human beings relate in an exuberant way,” notes McCann, who appeared in this composition.

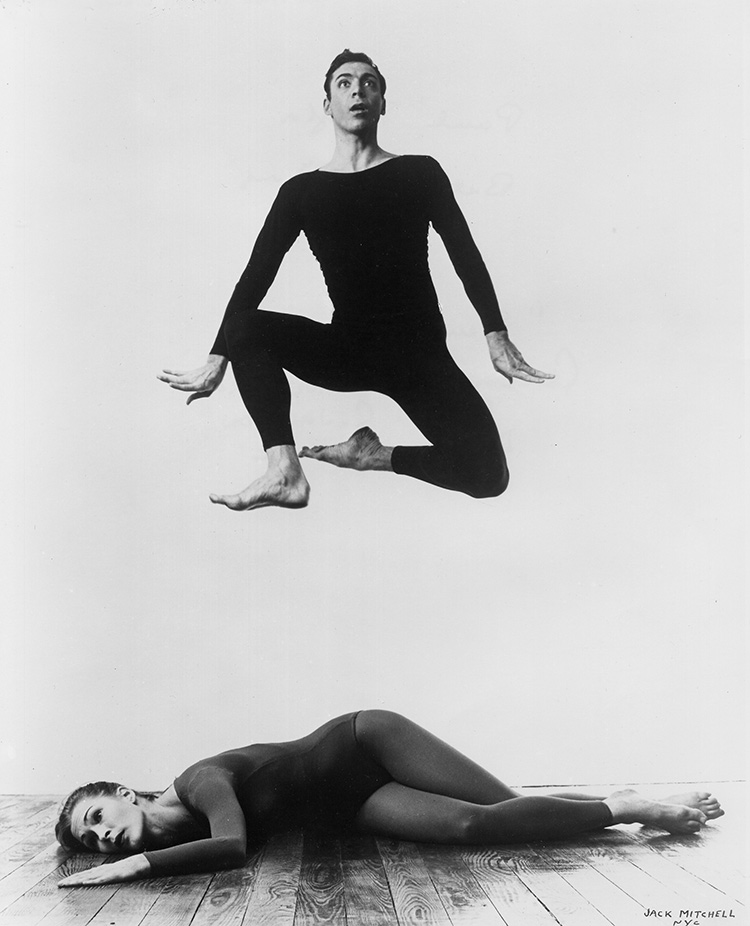

High and low: Paul Taylor and his favorite dancing partner, Rehearsal Director Bettie de Jong, in Scudorama, 1963. Photo by Jack Mitchell.

Though Taylor stopped performing in 1975, due to injuries, he continued as artistic director and choreographer. In fact, this proved a benefit, giving him more space to develop until his death.

In 2018, he tapped Michael Novak as artistic director designate, who would bring in other choreographers for new works, as Taylor did until he died later that year. McCann recalls Taylor speculating, “‘What happens when I die? I don’t want this to be a museum, showing the same pieces year after year.’”

Bringing Novak on board gave Taylor an added benefit—space to develop new works, which he did until his death in 2018. “One of the wonderful things about Paul Taylor is that his pieces can be timeless … they comment on humanity and how communities face issues, and so they can be recycled because the same issue is repeated a decade or more later,” McCann notes.

Seeking redemption: Jamie Rae Walker, Michael Trusnovec, and Amy Young in Speaking in Tongues. Photo by Paul B. Goode.

One example is the seldom seen Speaking in Tongues, which Taylor created in 1988. Its focus is on the religious extremism making headlines when those high-profile evangelists Jim and Tammy Bakker were caught stealing from their followers. (Today, once again, Kingdom of God church leaders are in the news—arrested for allegedly running a multi-state forced labor scheme that raised more than $50 million.) Taylor’s meditation on religious extremism won an Emmy for its TV broadcast in 1992.

Rehearsal scenes: Robert Battle and Lauren Lovette. Photos by Noah Aberlin.

And just as its founder desired, the Paul Taylor Dance Company, continuing to produce new works, is no museum. Michael Novak, serving as artistic director since 2018, has praised this season’s world premieres by resident choreographers Lauren Lovette and Robert Battle. In Lovette’s seventh world premiere for the Company, a disturbing piece titled stim displays dancers twitching and making other unusual movements. Set to John Adams’s Fearful Symmetries, this is Lovette’s personal exploration of living with ADHD.

In contrast is Battle’s high-energy Under the Rhythm, combining jazz, gospel music, swing dance, and a wild mix of music by Ella Fitzgerald, Wycliffe Gordon, Mahalia Jackson, and Steve Reich. It’s so swinging, you’ll want to jump up and join in.

That sense of engagement, found in all the dances, is the Paul Taylor effect!

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including The Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the Magazine. She has co-authored many books, including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

For other NYCitywoman articles by Suzanne Charlé, see: