ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget … Beatlemania, 1964 & 1966

History in the making: two hectic, frenetic Washington, D.C. concerts, two years apart, complete with star-struck, screaming teens

By Karen Feld

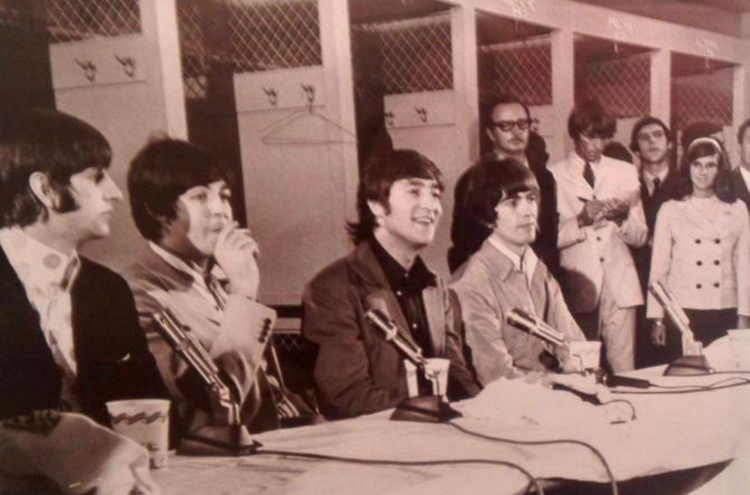

The Beatles score a big win at the D.C. Stadium locker room, August 15, 1966. At far right is this article’s author, Karen Feld, wearing her headband.

November 9, 2023

November 9, 2023

I remember “the day the music died” in February 1959. Three rock legends—Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens—went down in a private plane crash in Iowa. Those deaths left a void in the American pop music world that opened the door for the British Invasion. Had they lived, perhaps demand for the Beatles would have never reached the height it did.

We don’t have royalty here in America—and have long been thirsty for it. American teenagers were awed by the Beatles and their unique British sound, played over and over on the radio, on 45s, 78s and LPs. As a teenager at the time, and a Beatles fan, I was curious to see what the hullabaloo was about—and what it wasn’t—when they made their first U.S. appearance in 1964. It was a hectic, frenetic scene. The sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll are now documented—gospel truth, recorded in history, which, looking back, it’s hard to believe I was a close-up witness to.

But that’s what happened. I grew up in a show-biz-connected family. My Dad, a snake oil salesman-turned-record-store-owner-and-impresario, promoted several dates on the Beatles’ U.S. tours—their final, in 1966, as well as their first. As thrilling as it was for most kids, seeing performers live, on stage, has never awed me. I was a quiet teen who preferred staying home with a book; but attending concerts was not an option in my family.

The Beatles TV appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show confirmed their “royal” status. Then they headed to D.C. to perform their first live and much-anticipated U.S. concert, held at the now-defunct Washington Coliseum. That was on a snowy Feb. 11, 1964. Surprisingly, they exhibited a kind of naïveté—not only by today’s standards, but even back in that less jaded time, within a year after JFK’s assassination. The group, accustomed to the confinement of a recording studio, performed for the first time on a stage, even moving their own equipment, including Ringo’s drums, with little concern for personal safety. Jay and the Americans—who’d played at my Sweet 16 the same year—and the Righteous Brothers opened the show. The audience didn’t notice that George Harrison’s mike malfunctioned. Fans threw jellybeans at the stage, causing him to complain every time one hit his guitar string, inducing a bad note. At the after-party at the British Embassy, one girl got close enough to clip a lock of Ringo’s hair, causing the foursome to abruptly depart and head back to the Shoreham Hotel, where an entire floor had been vacated for them.

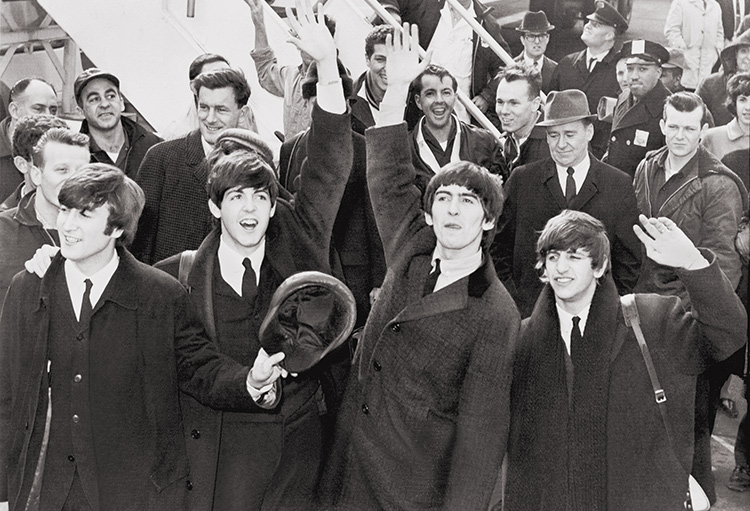

The year was 1964, and the foursome were wearing their narrow ties as they arrived at JFK for their first foray into New York.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

What a contrast to the muggy afternoon two years later, August 15, 1966. That was when, as a college freshman dressed in a proper blazer and pleated skirt, my long hair pulled back with a headband, I stood next to the Beatles at their press conference and observed history being made in the world of pop culture.

We stood in front of the emptied lockers at their pre-performance press conference in the Washington Senators locker room at D.C. Stadium, later renamed for RFK. Although a native Washingtonian, I was never a sports fan, so hanging out in the Senators locker room, even with the Beatles, wasn’t a big deal for me.

The D.C. concert turned the Beatles’ second U.S. tour into a news event, not just because they’d set foot again on U.S. soil, but because the Ku Klux Klan banned them after John Lennon claimed the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ. The controversy the band stirred with their wit and irreverence was a two-edged sword—but deemed politically incorrect even at that time. Washington, albeit the nation’s capital, had the ambiance and attitude of a small Southern town. Radio stations in the South boycotted Beatles songs. Organized protests occurred. A pre-show afternoon press conference was scheduled. With questionable safety a priority. I remember feeling the tension I saw, what with the Ku Klux Klan demonstrating outside the venue pre-concert—they were mostly dressed in red, white, and green robes, with six men in white sheets and hats carrying a placard. I don’t remember what the placard said, but protesters were spotted carrying signs, “God Forever Beatles Never” and “Burn the Beatles.” The audience inside was predominantly white teenage girls.

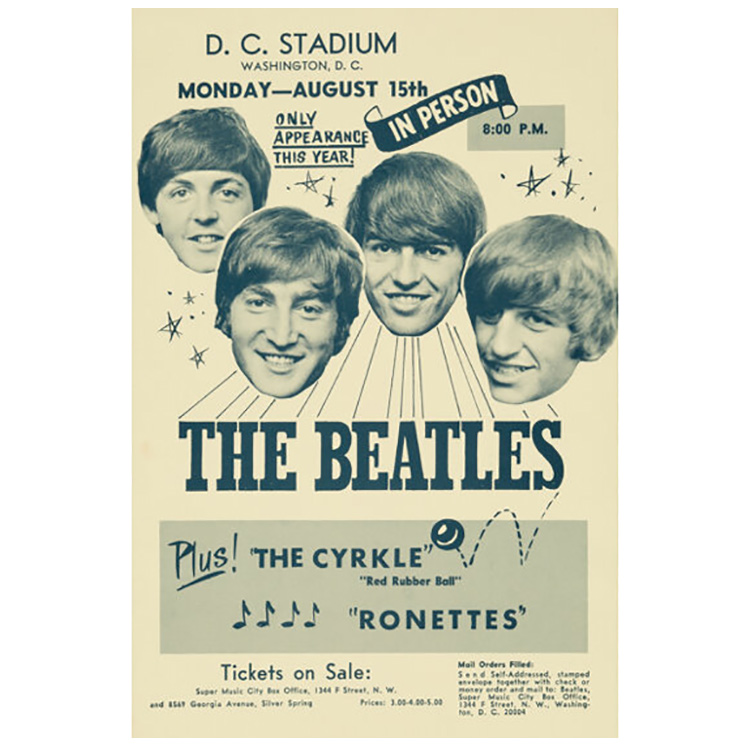

We remember the Ronettes. But who was (or were) The Cyrkle? Answer: They charted two Top 40 hits, “Turn-Down Day” as well as “Red Rubber Ball”.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

In anticipation of this steamy August day, I was privy to the band’s promoters discussing logistics—whether to install a roof on the stadium in the event of rain; and how to get the band out of the venue safely. In an effort to avoid the crowd of giddy groupies, plans were even discussed to rent at least one coffin to carry them to their limo. I don’t know if they anticipated the four superstars cramming into one or they had a plan to splurge on four separate containers. That option, in fact, had been used on occasion, or so my dad told me—although I never believed all of his often-exaggerated lore and don’t recall if it actually happened that evening.

Organizers had a 600-foot-long fence built in the outfield to block fans from mobbing the stage. Despite a police presence numbering 500, including women, surrounding the stage—an unusually large presence at that time—a clever group of locals impersonating the Cyrks— the opening act, along with Bobby Hebb, Ronnie Spector, and the Ronettes. and the Remains—got as far as the dressing room to meet the Beatles. (This was pre-internet, so unless a band had appeared on national TV, not even security knew what they looked like.)

Security for the press conference was tighter still. Not even reporters from neighboring Baltimore were admitted. Writers and camera crews had had to have their full ID credentials verified ahead of time, causing assignment editors at major media outlets to balk. Who do the Beatles think they are?—they wanted to know. Stringent security was otherwise unheard of back then—even at the White House.

But despite the hype and appeal of their music, it wasn’t a terrific concert by any stretch of the imagination.

Tickets priced at $3 to $5 didn’t sell out, although the performance attracted some 34,000 fans—four times as many as at the Beatles’ first D.C. gig. Their unique sound, achieved in a recording studio, was difficult to duplicate live at the time, especially outdoors in a ballpark. Almost any music would have been impossible to enjoy in the presence of star-struck, screeching teenage girls. The Beatles performed 11 songs in a half hour, with no encore, before being spirited away in a limo—one among the many decoys. Little did the audience know they were witnessing what would be the band’s final American tour.

I remember a lot of commotion and chaos. One officer stuffed a bullet in each ear to block the deafening sound. In retrospect, just being there witnessing history in the making was the thrill. More than a half century later, it’s still about the conversation and THE HOOPLA—not the 30-minute concert. The band, although stamped with Ed Sullivan’s approval, was not prepared for prime time in live venues. Since their image was larger than life, most fans were never aware of their very brief stage career. The British Invasion had begun, and royalties from recordings soared. It was Beatlemania!

Karen Feld, an award-winning writer, penned a Washington-based syndicated personality column for many years, chronicling social history through the intersection of politics and entertainment. She also dished on-air political gossip weekly with Joan Rivers.

Read more by Karen Feld: