ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

What Aging Parents Don’t Want to Hear

Are your adult children overprotective—or not protective enough?

By Claire Berman

Several years ago, I wrote a book aimed at helping adult children manage the challenges of caring for their aging parents. I interviewed women and men across the country about their struggles and successes. Sharing our stories, we helped each other cope. I also spoke with members of the helping professions: geriatricians, social workers, elder law attorneys, administrators of assisted living facilities, and just about anyone and everyone who could shed light on the subject. Everybody, that is, but the aging parents. That now strikes me as a glaring omission.

No doubt it’s because now I’m an aging parent and look at the issue of parent care anew…and from a different perspective. For example, I nod in agreement when the son of a friend expresses concern to me about his dad driving after dark, but I also understand when his father complains of “being badgered by my kids about my driving.” So I ask: How serious a problem is the father’s driving? And how capable is the father of making his own decisions? Certainly there are situations (far too many, alas) where the assistance or intervention of adult children is clearly needed, but what if that’s not the case? As parents get older, our attempts to hold on to our independence may be at odds with even the best-motivated “suggestions” from the best-intentioned children. We want to be cared about, but fear being cared for. Hence the push and pull when a well-meaning offspring steps onto our turf.

Case in point: My friend Julia and I meet at a local museum. She’s 75, a retired editor and volunteer docent. Over lunch, we catch up on family news—kids, grandkids. She takes out an iPhone and shows me pictures. I ask about her daughter Brenda, who recently moved back to the East Coast from Chicago. “It must be nice to see her more often,” I say. Julia sighs. “Yes, but—” she says. “Whenever Brenda drops by, I’m not sure whether she’s come to visit or to check up on me: Does my home meet the clean test? Is the yogurt in my refrigerator long past its ‘use by’ date? Do I really need the rug in the hallway—you know, the one I carted home from Morocco some years ago? Area rugs can be dangerous, Brenda tells me. I feel like I’m constantly being assessed.”

I have some idea of what Julia means. My husband and I have taken to checking the due dates of groceries prior to a visit from any of our three sons, who even ask our grandkids to go through my spice cabinet. For them it’s a game, except I don’t feel like playing. Ten years ago, I probably would have joined in the fun. Now I’m more sensitive to being criticized. “There ought to be a book called Aging Parents Speak Out,” I say to Julia. “Go for it,” she says.

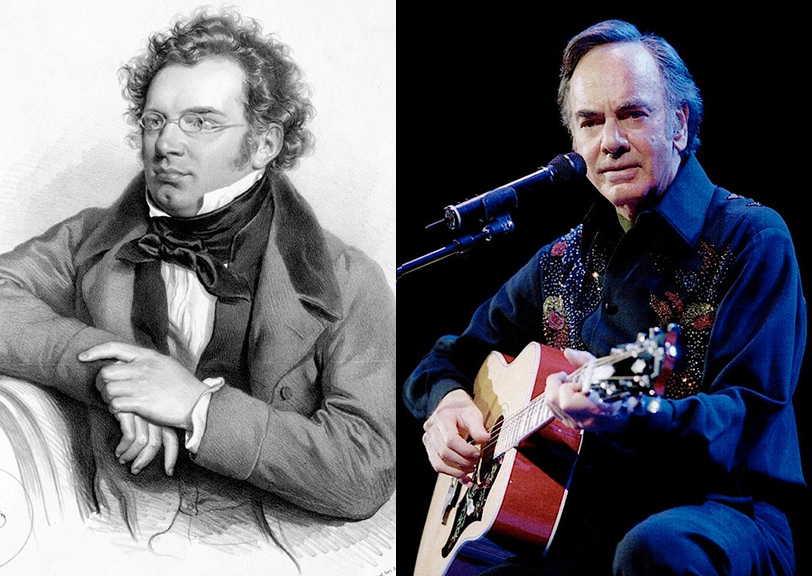

A week later: My friend Elinor and I are discussing a number of recently aired tributes to Frank Sinatra when we block on the name of another singer of that era. Some back and forth… ”I see an M,” I say. Running through the alphabet often works for me… Triumphantly, Elinor comes up with: “Mel Torme.” It’s the right answer. She expresses relief. “My son and daughter-in-law have made me very self-conscious about my memory,” says Elinor. “Whenever they catch me in a lapse like not knowing the day’s date—I mean, I know it’s a Thursday, but is it the 21st or 22nd of the month—or if I sometimes struggle to find the right word (as we all do), they exchange these long, meaningful looks. The only thing their scrutiny accomplishes is to make me more nervous in their presence.” Has she talked to them about her feelings? “No,” says Elinor, “I do enjoy their company, but I also find myself looking for excuses to see them less often.”

So what are we looking for in relationships with our adult children? Mary P. Gallant, Associate Professor at the School of Public Health of the State University of New York at Albany, explored the issue in interviews with focus groups of older parents. Among her findings: Older parents “express strong desires for both autonomy and connection in relationships with their adult children, leading to ambivalence about receiving assistance from them. They define themselves as independent, but hope that their children’s help will be available as needed. They are annoyed by children’s overprotectiveness, but appreciate their concern. They use a variety of strategies to deal with their ambivalent feelings, such as minimizing the help they receive, ignoring or resisting children’s attempts to control….”

We pay attention to the nuances. My friend Pam, a feisty lady who’s resumed her routine of early-morning speed-walking after two knee replacements, talks of detecting “a certain new tone” in calls from her daughters. “There’s caring, but there’s also condescension,” she explains “They don’t mean any harm, I know, but I often feel infantilized.” Has she told them of her feelings? I ask. “No,” she answers, then smiles broadly and adds, “But I have been thinking about it.”

According to a recent Pew Research Center Report, telephones dominate communication between parents and children. But are we really communicating? An aging parent describes a phone call from her fifty-something son. “He’ll ask. ‘How are you and Dad?’ She typically answers: ‘We’re fine, just fine’ in her perkiest possible voice. But she ponders, Should I tell him that we’re not as able as we used to be, that we could use some help with the grocery-shopping, the gardening?… It’s important for his father and me to be seen as independent… Besides, our son should know without asking that we could use some help in removing the air conditioners for the winter..” We parents engage in magical thinking about “what our adult children should have known”…“what they should have done…”. And then we’re disappointed if the children don’t come through. The onus here is on us to speak up. The clearer we are in describing our feelings and stating our needs, the better our chances of having those needs met.

At a celebration of the 80th birthday of my friend Leah, I’m seated at a table for eight, all women of a certain age. My very own focus group, I find myself thinking. At the main table, Leah is surrounded by her family: two sons, their wives, seven grandchildren. A photographer is taking pictures. It’s a beautiful family, all at my table agree. I have found my opening. “While we’re on the subject of families…” I begin, and ask the women about their own families, specifically about anything they might want to say to their own adult children. “I’d just want to say ‘Thank you’,” says Sheila, “and I do say it all the time.” Sheila explains that she was sidelined by a back ailment this past year and “my daughters, despite their busy social and professional lives, bent over backwards to do everything for their father and me. I’m just so grateful they were there.”

“What I’d want to say to my daughters?” asks Helen, seated to my right. “I’d want to tell them, ‘Buzz off..’” Widowed early in her marriage, Helen is fiercely proud of having managed as a single mother. Her daughters are now in their early fifties. “They’re always offering to do this, do that and do the other thing, and it just drives me crazy,” Helen says. And why is that? “It tells me that they think I’m not competent,” she explains. “The result is that I’ve stopped telling them when something is wrong.”

Our conversation is brought to a close by the sound of a spoon clicking against glass. Leah’s older son rises to offer a toast. “To the birthday girl,” he begins, going on to extol his mother’s virtues—and they are many. Other toasts follow. There isn’t a dry eye in the room. Finally, Leah takes the floor.. “To my wonderful family…” she begins. I guess that says it all.

Claire Berman has written nine books on such topics as caregiving, divorce, step parenting, and adoption. She was a contributing editor at New York and has written for The New York Times Magazine, Parade, Reader’s Digest, and other national magazines.