ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget…Ornette and Otello—Early ’60s

That would be Ornette Coleman, performing free-form, rule-breaking jazz at the Five Spot in Downtown New York … and Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, played at home alone, in a bedroom in Queens

By Linda Dyett

Ornette Coleman performing in 1971. Photo by Jean-Pierre Roche.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

September 13, 2023

September 13, 2023

September 1960. I was a college sophomore, living at home with my parents in Bayside, close to the far eastern edge of that outer borough, Queens. Back then, Queens, to me, not only was not Manhattan, it lacked even the moderate clout and hints of urban smarts that I ascribed to Brooklyn and the Bronx.

On a certain Saturday night, I had a date—with a boy who was also from Queens and who, like me and everyone we knew, longed to live in, or at least hang out in, the City. The tantalizing, always-beckoning City was where we were headed, taking first the meandering Q27 bus and then the IRT Flushing line on its elevated-underground route, zooming ruler-straight past Corona, Jackson Heights, Woodside, et al., until that superb moment right after Queens Plaza, when the train careens sharply left, offering an instantaneous panoramic view of the skyscrapers directly across the East River. Those skyscrapers were beckoning to us—us.

We’d heard that the Ornette Coleman was breaking with convention, loosening things up with his alto saxophone—and we could catch him doing so at that now-long-gone, hallowed-in-memory jazz club, the Five Spot, at its original location on Cooper Square, along the Bowery. Back then, that part of town, due east of Greenwich Village, was an undefined nowhere-ville, yet to be named the East Village and endowed with realtors’ cachet. But word was out that the regulars playing at the Five Spot—legends in their own lifetimes—included Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and Charles Mingus—and among the locals who just happened to drop by to catch their shows were, oh, Willem de Kooning, Jack Kerouac, and Frank O’Hara. Not to mention a guy from uptown by the name of Leonard Bernstein, who’d recently become director of the New York Philharmonic. He showed up too.

“A new underground formed here, and painters, writers, and jazz musicians joined forces to stage an assault on the very definitions of art, music, literature, and theater,” said the historian Terry Miller, author of Greenwich Village and How it Got That Way.

“It was just like a neighborhood bar…only it wasn’t Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood! It was more like Mr. and Ms. Wino’s Pre-Memorial Service.” So said the composer-conductor David Amram in a quote appearing in Lannyl Stephens’ article, “Five Spot: Once The Hippest Place on Earth,” published in 2022 in villagepreservation.org, the blog produced by the Village Society for Historic Preservation. Stephens is Director of Development and Special Events for that organization.

Of course we had to be there.

The club’s storefront entrance was unassuming, but once inside we found a cigarette haze so thick, we could hardly make out the tiny stage where the Coleman quartet was about to play. Growing used to the darkness, we spotted wizened faces, 20 or 30 years older than us (wasn’t one of them Jackson Pollock’s?) crowded at the small tables. Oh, right. These were Manhattanites, while we surely looked like eager rubes who’d managed to cross some sort of barrier and trespass into the center of their world. Or so I thought. But to my delighted surprise, we received zero short shrift—none of it. We were warmly greeted and given a really good table. I’m going to use the word class; we were treated with class.

I think I know why. We were about to witness something radically new. The music we would hear—we did hear—was free-form, ragged, strident, suggesting upheaval. I especially remember “Lorraine,” from the Tomorrow is the Question! album. It suited the expectant mood, the emerging energy of the time—as the stolid, Eisenhower 1950s gave way to the JFK-inflected early ’60s. And we young inhabitants of the Mod era, which had yet to give way to the civil rights-Vietnam-sex-drugs-rock ’n roll-no-longer-Mod late ’60s—we were poised to receive the signal that this rule-breaking jazz was sending us. Get yourselves ready for change, it said.

It felt as if Coleman and the Five Spot were entrusting especially us, the kids in the room, with this news to pass along to our peers—the burgeoning generation that soon enough would lead the way to the Youth Quake. So we were treated throughout the evening with aplomb, and I, an 18-year-old looking more like an underage 17, was served the scotch on the rocks—no questions asked—that friends had advised me to order. Once on stage, Coleman even nodded to us. Surely he of all people was onto the fact, even in the pre-seismic early ’60s, that if tomorrow was the question, we could well be the answer.

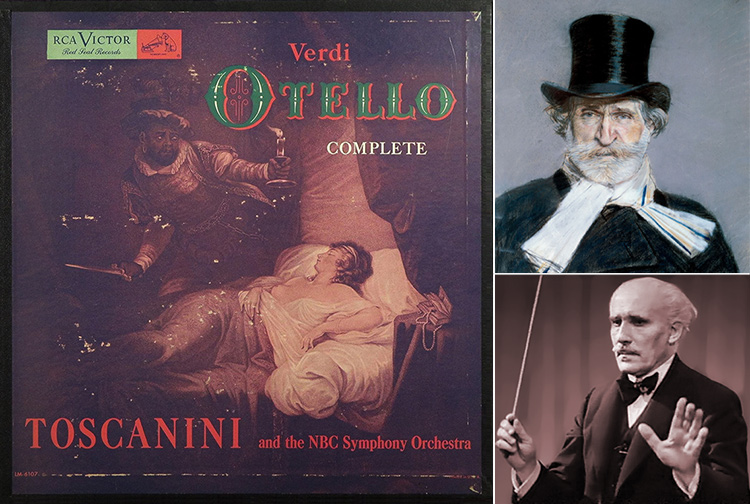

The RCA Victor lurid Otello album cover; a top-hatted Verdi and a baton-swinging Toscanini.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

A couple of years later, still living at home, I was listening to Otello on the record player in my bedroom. For a comprehensive college arts exam, I was to compare the Verdi opera with Shakespeare’s Othello. So into the City I’d gone. Destination: the ever-reliable Record Hunter, on Fifth Avenue just above 42nd Street, where I nabbed the Toscanini-NBC Symphony Orchestra LP, combining two 1947 radio broadcasts performed by the soprano Herva Nelli (a Toscanini favorite, as Desdemona), the tenor-with-baritonal leanings, Ramón Vinay (in the title role), and the baritone Giuseppe Valdengo (Iago).

Despite its less than perfect sound quality, this recording has been rated one of the best Otello renditions extant. Stereo? Mono? No matter. Hearing it, I was seared. As with Coleman, it had me pondering (seriously)—what was that exquisiteness, from start to finish? How was such a thing even possible? It seemed to me to be the perfect musical counterpart to Shakespeare’s play, of tragic loss and betrayal told with nuanced care. To this day, I treasure Othello more than even Hamlet or Lear—and I think that damn Verdi and that rapscallion Toscanini, with his impossibly perfect pitch, have plenty to do with it.

In his introduction to the Otello broadcast, the NBC Radio and later TV announcer Ben Grauer noted that Toscanini, as a young cellist, played in that opera’s world premiere, conducted at La Scala by Verdi himself, 60 years before the radio broadcasts. Which had me wondering: With proximity—inside the orchestra pit, the composer himself at the baton, his hand and eye gestures registered up close—was Verdi’s greatness transferable? Was it contagious? Maybe at least it set high standards for those, like Toscanini, who were amenable and impressionable. (For his 2015 Broadway musical Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote a hip-hop song on this very subject—the allure of proximity, of being in an inner sanctum. It’s called “The Room Where It Happens.”)

But back to Ornette at the Five Spot and the Otello LP—my two most spellbinding, verve-defining music experiences. In one, I mingled with a group of beyond-cool New York artist-bohemians who were far more credentialed than the usual humdrum beatniks around town, in an atmospheric cabaret where the performers were breaking the rules of jazz. In the other, I was alone in my utterly chaste bedroom in Queens.

Both occasions felt transcendent. Coleman’s quartet performance was live, and I loved sharing in its jarring beauty—new to me and so of-the-moment—not only with a date (who wasn’t even a boyfriend), but with a roomful of strangers. It was almost erotic. (There must be something primal about listening to music in a group. Isn’t that what concerts are all about?) Yet mulling it over, listening to Otello all alone, with no libations, no downtown ambiance, no possible de Kooning sighting—I found that captivating, too, in its unadulterated purity. So OK, the two performances are now officially equal favorites of mine.

Linda Dyett’s articles on fashion, beauty, health, home design, and architecture have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Monocle, Afar, New York magazine, Allure, Travel & Leisure, and many other publications.

Other articles in this series: