ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

I’ll Never Forget … Billie Holiday, June 15, 1957

The night the music came alive at the Loew’s Sheridan Theatre, New York City

By George Blecher

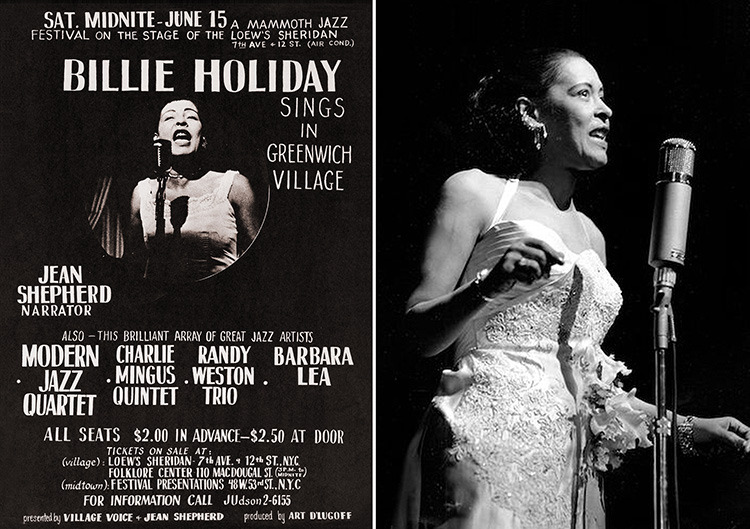

The main event: Billie Holiday topping the bill at the Loew’s Sheridan Theatre in Greenwich Village, “SAT. MIDNITE,” June 15, 1957 (but delayed a few hours); and onstage at Basin Street Cafe, 1950. Photo © Herman Leonard Photography, LLC. (Visit at hermanleonard.com)

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

August 16, 2023

Three o’clock in the morning. A humid night in June 1957. Twenty-five hundred people packed into the Loew’s Sheridan Theatre in Manhattan—an opulent, aging movie palace built on the odd triangular block where 7th Avenue and 12th Street intersect. Everyone was waiting for Billie Holiday.

The air conditioning in the theater had conked out; we were all dripping with sweat. Jean Shepherd, whose late-night radio monologues were a kind of embodiment of White kids’ yearning to be as cool as the Black jazz musicians they admired, was anything but cool that night. His shirt and tie were open, his suit glued to his body. All he could do was stand alone on the enormous stage and whine an apology:

“She’ll be here. I promise. She’ll be here.”

We had just sat through an exceptional concert. This was the era when all-star concerts featured one brilliant jazz musician after another. Starting at midnight, we had listened to, among others, Randy Weston, a pianist whose huge hands had the gentlest, most feathery touch; Charles Mingus’s raucous, passionate dissonance; and the elegant Modern Jazz Quartet, who played a music so refined and self-conscious it almost seemed distilled.

But we’d come to see Billie. She’d been barred from New York nightclubs for years. Few in the audience had heard her in person. We were told that she’d be arriving after a gig in Philadelphia.

The young Billie Holiday of the late 1930s had had a time-sense unlike anyone else’s: she floated through a song rather than sang it, bending notes and extending vowels into diphthongs. She could find the emotional center of a lyric and enter it like a second skin. When she sang “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” she was flirtatious and funny; in “I Must Have That Man,” she was exposed and vulnerable; in “Easy Living,” languorously content. I must have listened to Lady Day, George Avakian’s Columbia compilation of her greatest recordings of 1937-41, at least a thousand times.

In exile: After serving her 1947 prison term for narcotics possession, Billie lost her New York cabaret card. But she played Club Bali in Washington, D.C. in 1948. The pianist Bobby Tucker worked with her for several years. Photo by William Gottlieb.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

By the late ’50s, however, she had become more than a great musician; to a circle of jazz fans, she was a dying swan, a tragic figure. Her romance with the tenor saxophonist Lester Young was legendary: Billie the prostitute’s daughter and Lester the sensitive, velvet-toned player who had brought a new intimacy to jazz. Anyone with ears could hear the love in the perfect little phrases he invented behind her vocals. He had dubbed her Lady Day; she called him the President. But we read how racism in the Army had broken Lester’s spirit and turned him into an alcoholic, how the narco squads hounded Billie out of New York. Pieced together from the copy on record jackets and the pages of Downbeat, their story took place in a white-hot crucible where art, racism, and pathos were smelted together.

By the 1950s, Billie’s voice was cracked and tattered. In her late recordings she sounded infinitely sad. What kind of suffering had she gone through to feel such despair? It was beyond our experience—we were middle-class White kids, in good high schools and colleges, heading to prosperous careers. Billie had sung in whorehouses, on the streets. It was only by the wildest stroke of luck that a record executive “discovered” her, and by age 19 she was recording for Columbia Records—the most prestigious label of the time. Though we couldn’t admit it to ourselves, we sensed that our love of jazz, and especially of her, was a kind of slumming, and that her fans and record companies used her, never fighting for her right to perform in New York clubs, treating her as an object of pity rather than a great artist. And yet without the White Establishment, her genius would never have reached such a wide audience—including the sweaty gang of White kids in the Loew’s Sheridan, waiting impatiently that late night for a glimpse of Billie.

Miked up: At the first Monterey Jazz Festival, October 1958. Photo by Nat Farbman.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Three o’clock in the morning. We could hardly breathe. I seem to remember Jean Shepherd finally coming out on stage, his face flushed with relief: “Folks, she made it!”

Lights out. Complete darkness. A blue spotlight from high in the rafters found a fragile-looking woman in a sequined dress that looked like it was made of black diamonds. The theater went totally silent. The air seemed to cool down five degrees, no doubt out of a sense of relief that she actually existed.

The only mentions I can find online of her performance that night are polite but perfunctory. John Wilson of The New York Times noted that “once she had worked away a tendency toward thickness and lumpiness, she sang with a quiet passion that was deeply moving.” The Village Voice, which sponsored the concert, merely noted that she sang 10 songs, including her classic “Don’t Explain.”

For me, the experience went deeper than singing. Her voice was slurred and dreamy, as if she were talking in her sleep. It didn’t matter whether she hit all the notes. She wasn’t singing so much as talking—mostly lamenting, but occasionally looking off into the distance and chuckling at her own pain. What I heard was someone who had learned to express pure feeling through other people’s words, by somehow absorbing them until they became her words, her sounds, her emotions.

I don’t remember any individual songs—only the continuous sense of pain being transformed into art. Nor do I remember taking the subway home afterward to a bed far cozier than the ones Billie must have slept in. But I knew that her performance had changed me. I felt older. She had opened up for me a realm of grown-up emotions where I’d never been before, at least not consciously. I felt love, I felt awe. Most of all, I felt another person’s suffering, and my own.

I was 16.

Billie died two years later, at the age of 44. Her body lay for a year in an unmarked grave.

George Blecher writes for The New York Times and for a number of European publications about American politics and culture. See georgeblecher.com

Other articles in this series:

Enjoy more of George Blecher’s stories on NYCitywoman.com: