ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Good Books for Us to Read Now

This is the time to read tales about exile from beloved homes, to see William Blake’s vivid and strange vision, and to thrill to something that’s impossible to get right now: a baseball fix.

Photo of Sarah Broom by Adam Shemper.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom (Grove Atlantic). This beautifully written memoir of Hurricane Katrina provides timely affirmation that people can survive some of the most devastating natural disasters, learn from them, and move on. Youngest of twelve children in a black family, the author looks back on her family’s history, and on growing up in New Orleans East, a neighborhood not likely to appear on tourist maps. Theirs was the yellow house, a place ever in need of repairs, but functional—until the winds and the waters came and the bureaucrats refused to honor promises of renewal and restoration. This is a book of outrage and love. Winner of the 2019 National Book Award. –Claire Berman

Photo of Ann Patchett by Heidi Ross.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Dutch House (Harper), Ann Patchett’s eighth novel, is the closest thing to a contemporary fairy tale that I could imagine. It doesn’t feature a gingerbread house—except in the decorative details of the magnificent mansion that all the main characters live in at one time or another. The cast of characters: a loving brother and sister, their enigmatic father, a mysteriously absent mother, a vengeful stepmother, and warmhearted servants who provide most of the care the children receive. The story, told by Danny Conroy mostly about him and his older sister, Maeve, from childhood through late middle age, grabbed me from the beginning. I couldn’t put the book down and was sorry when I came to the end. I wanted more! –Sally Wendkos Olds

Photo of Emily Nemens by James Emmerman.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Let me pitch a fun spring training novel that’s only a little about baseball and a lot about the people involved in it. The Cactus League by Emily Nemens (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is set in Arizona in 2011. The fictional Los Angeles Lions, whose spring training site is in Scottsdale, has as its star Jason Goodyear, a superb outfielder—think Mike Trout—with a deplorable secret. The story also features an old coach, a rookie catcher, a pitcher with a bad arm, a homeless mother and child, an older woman who likes to bed ballplayers, and assorted others. The nine chapters (read “innings”) are cleverly interlocked tales of the anxiety and heartbreak just below the sunny surface of the major leagues. Who takes advantage of whom, how this place fits in the larger scheme of towns still recovering from the recession, how race affects the game: all figure in Nemens’s clever game. Even if you’re not a baseball junkie, you’ll marvel at Nemens’s insights. –Grace Lichtenstein

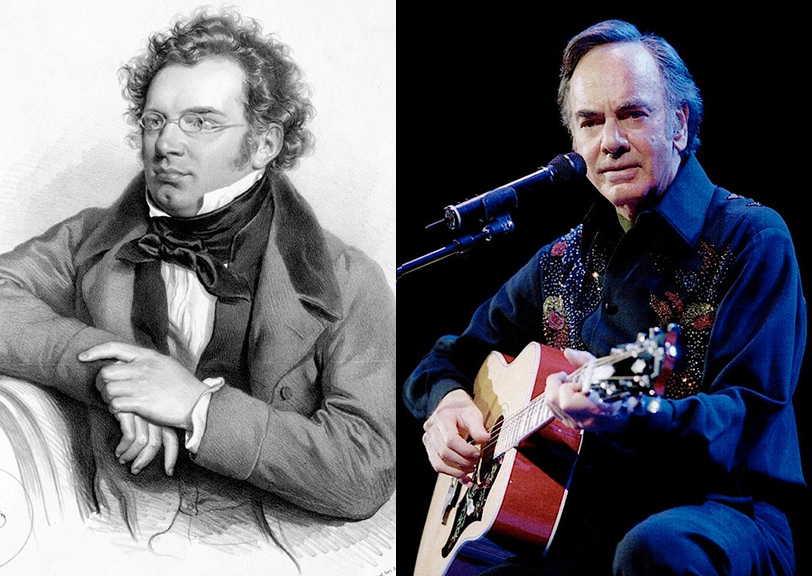

Left: William Blake catalogue cover, ‘Europe’ Plate i: Frontispiece, ‘The Ancient of Days’ 1827. Right: First Book of Urizen pl. 6, William Blake, 1796-c. 1818. Etching with paint, watercolor and ink on paper.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Two hundred years after his death, William Blake has been celebrated in an exhibition at the Tate in London—not for his renowned poetry but for his innovative engravings and watercolors. Now, thanks to the stunning catalogue William Blake (Princeton University Press), with over 300 images, we can sit here in New York and revel in the complex work of this free spirit.

Early in his life, Blake became acquainted with the prints of Rafael and Michelangelo. Apprenticed in his late teens to an engraver, by 1780 he had become an independent publisher, selling his works and those of others. His explanation for such a risky move: “The spirit said… ‘Blake, be an artist and nothing else!’”

His early works are vibrant examples of his independent spirit: “America: A Prophecy,” his poem and 18 engravings, revel in the colonies’ rebellion; The First Book of Urizen salutes the French Revolution and desires for freedom. An inveterate innovator, Blake developed new engraving techniques integrating text and images, which are displayed in his much-admired Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. (Yes, we all know how the poem “Songs of Experience” begins: “Tyger, Tyger burning bright.” I do wish, however, that our text books had included his marvelous images, images that go beyond simple illustration to expanding and re-envisioning the poems.)

He was against racial prejudice and slavery, as witnessed by his shocking etching/engraving “A Negro hung alive by the Ribs to a Gallows” for a book published in 1796, and an advocate for women, designing the frontispiece for a book by the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft.

Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing, William Blake, c. 1786. Watercolor and graphite on paper.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Over the years, Blake’s patrons—most of them members of a circle of radical thinkers—bought and commissioned temperas and watercolors and collected illustrated works Blake referred to as “Historical & Poetical,” including Milton’s Paradise Lost, Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the Bible.

These let us see the world through his eyes: his distrust and disdain for the Age of Reason and its intense focus on science, while ignoring the important moral, social and cultural aspects of life. In the satirical ink-and-watercolor “Newton,” Blake slyly targets the celebrated scientist and designer of the stock market for his regimented rationality.

Time and again, he records the contrary aspects of mankind: the battle of slavery vs fulfillment, tyranny vs freedom. There are horrific images of death and depredation; the artist explained that one of his last and darkest works, “The Ghost of a Flea,” was the portrait of a creature that approached him during a séance.

Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car, William Blake, 1824-7. Ink and watercolor on paper.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Here too are scenes underscoring Blake’s abiding faith in humanity, a belief that everything is holy—a philosophy Blake held to his final years, when, encouraged by patrons, he illustrated Dante’s Divine Comedy (for which he learned Italian) and Pilgrim’s Progress, which displays some of his most imaginative imagery.

Without blinking, Blake creates mesmerizing artworks detailing the best and worst of human nature. In doing so, as one critic put it, “He blows away Constable and Turner—and that’s with his writing hand tied behind his back!” In a salute to Blake’s remarkable spirit and talent, the curator arranged to have one of the artist’s last and most iconic images—“The Ancient of Days,” the same image on the book cover—projected on the giant dome of London’s St. Paul Cathedral, fulfilling Blake’s “lifelong dream to be an artist with real public impact.” –Suzanne Charlé

Newton, William Blake, 1795-c. 1805. Color print, ink and watercolor on paper.

. . . . . . . . . . . .