ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Don’t Stop Reading Now

Our book reviews zoom into Shakespeare in America, panthers and cobras transformed into fine jewels, Chippewa lives, and a new take on the tried-and-true western

We bipeds, with our naked hides and our limited prowess and speed, have long been awed by the strength, ferocity, grace, agility, and—for lack of a better term—hauteur of our fellow members of the animal kingdom. Not only other mammals, our nearest kin, but scorpions, snakes, butterflies, spiders, lizards, lions, and tigers too. No wonder we honor and celebrate these creatures by making and wearing jewelry in their image, studding it with gold, silver, platinum, and gemstones whose shimmer and glow mimic these animals’ built-in bioluminescence and astonishing shapes. What’s more, by wearing, say, a tarantula or butterfly brooch or a snake necklace, it’s as if we are sharing in the power of these creatures.

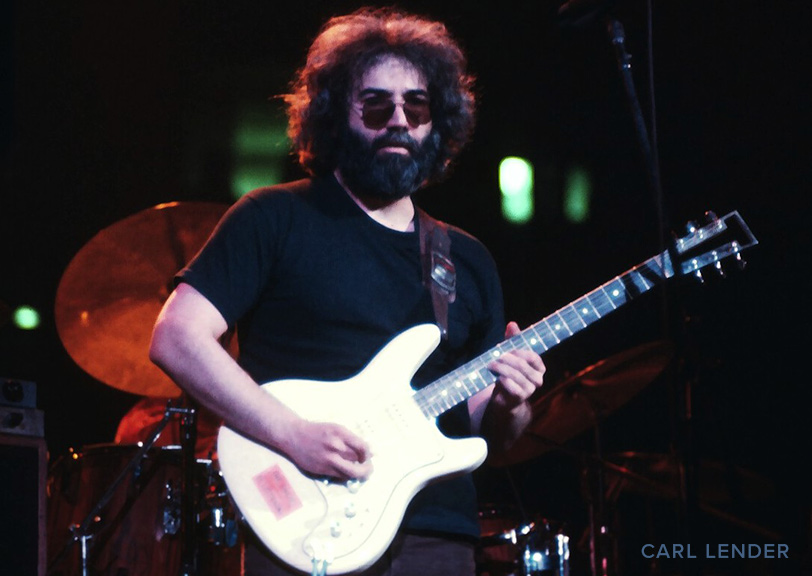

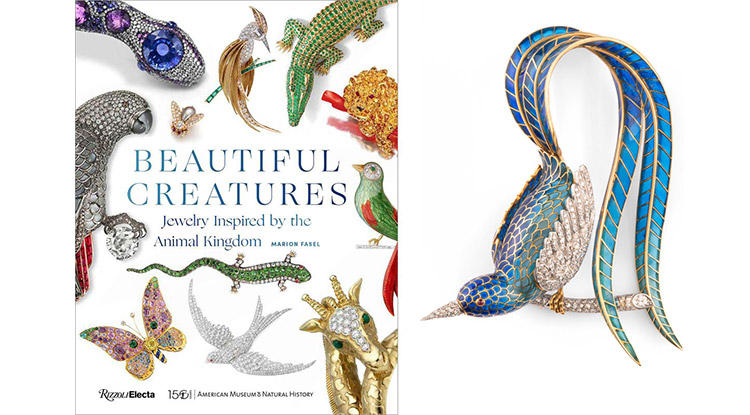

Animal jewelry of the last century and a half, as rendered by Cartier, Boucheron, Bulgari, Tiffany, David Webb, and other fine jewelers, is the subject the forthcoming inaugural exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History’s completely renovated Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals. (The date has yet to been determined.) Marion Fasel, the fine jewelry historian, has not only done the curating, but has profiled each item originally selected for the exhibit in her latest book, Beautiful Creatures: Jewelry Inspired by the Animal Kingdom (Rizzoli).

It’s all there—the interplay of humans and nature, of inanimate becoming animate (and vice versa), along with jewelry-making techniques. And true to zoology, the book is divided into air, water, and land sections. In each, Fasel documents the way certain animals became popular jewelry subjects reflecting their times. Dragonflies abounded in the West once trade with Japan reopened in 1953. Birds were frequently rendered during the French Occupation. And in 1949, Cartier’s platinum and white gold Panther Clip Brooch, studded with sapphire cabochons, single-cut diamonds and pear-shaped yellow diamond eyes, was perched in watchful, sinewy triumph atop a huge Kashmir sapphire cabochon—all in all, a symbol of postwar exuberance. It was purchased by the Duchess of Windsor.

My favorite pieces in this book change each time I open its pages. Here are two I’m partial to right now:

From 1942, the Lion’s Paw Shell Brooch by the Sicilian nobleman jeweler Fulco di Verdura, who was a pal of Coco Chanel. He went and bought a scallop shell at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Gift Shop, and into its channels he placed shoots of gold set with sapphires and diamonds, to represent the paw’s tendons. Here we have a freshwater bivalve (the scallop) doing due diligence as one of the extremities of a feline (the lion) found far away in Africa and India.

And from 2011, I’m taken with the Armenian-Turkish jeweler Sevan Biçakçi’s King Cobra Cuff. Gold lines its underside, while the silver on top is covered with yellow, brown, and black diamonds, representing scales. The snake’s body coils around the wearer’s wrist, while over the finger slip its gaping jaws—a superb meshing of reptile, minerals mined from the earth, and the human being to whom this cuff is affixed. –Linda Dyett

. . . . . . . . . . . .

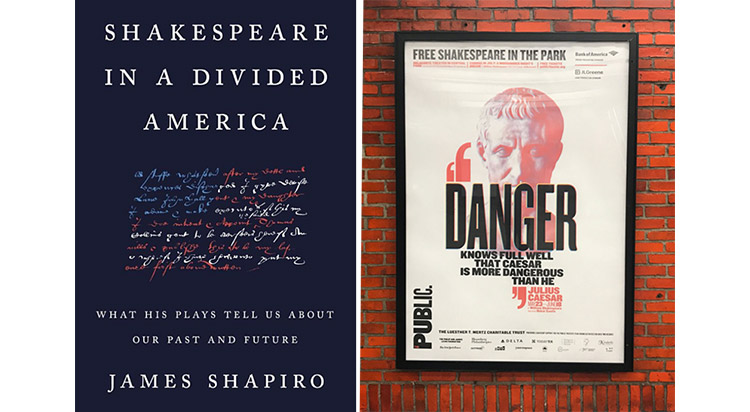

As we head toward summer and (fingers crossed) the reopening of Shakespeare in the Park, James Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America (Penguin Books) is a must-read. With wit and deep insight, the eminent Shakespearian scholar gives us a look, as the subhead details, at “what his plays tell us about our past and future.”

Detailing eight periods of history, Shapiro relates the ways the Bard’s plays have reflected the discord in our nation over subjects including immigration, class warfare, adultery, and interracial love. During the Revolutionary War, both sides rallied to the call “to be or not to be.” Leading up to the Civil War, both North and South declared Othello theirs, for totally opposite reasons. At the time, most households had only two books: the Bible and Shakespeare’s plays. Lincoln, self-taught, grew up on the plays and would frequently recite entire scenes to his staff. John Wilkes Booth was also a devotee, invoking Julius Caesar in his diary soon after he shot Lincoln.

In fact, Julius Caesar is closely linked to Shapiro’s decision to write the book. An advisor to the Public Theater, he was intimately involved with the 2017 production of Julius Caesar in Central Park, in which the Roman dictator was played by a Trump lookalike, complete with MAGA hat and gold-plated bathtub. Coming just months after Trump’s inauguration, the production stirred such controversy that protestors invaded the stage, requiring security guards to pull them off. Soon, threatening emails were pouring into the inboxes of members of the production and also to other troupes, including the New York Classical Theatre and Shakespeare Dallas. “Go fuck yourselves,” ranted one. “May you each die a more horrible, terrifying death.”

And the future? Today, notes Shapiro, “no writer’s work is read more” here in the States. Certainly, Shakespeare’s plays, many of which were written during pandemics, speak to us. Yet Shapiro reminds us that “in 1642 Parliament ordered ‘public-plays shall cease,’” and the Globe Theater was closed and torn down. “The divisions had grown too great.” –Suzanne Charlé

Public Theater’s 2017 production of Julius Caesar. Photo by Joan Marcus.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Photo by Seth Pomerantz

Outlawed (Bloomsbury), by Anna North, is like no other western you’ve ever read. Set in a mythical United States in 1894, it tells of women who are banished when they prove to be infertile. Most are forced into nunneries. Ana, however, is a valued midwife and healer. She escapes to join a group of outcasts, the Hole in the Wall gang, who maintain a tenuous existence away from society. Adventures, disguises, and robberies ensue. The gang is led by the charismatic Kid, who is a prototype for the non-binary hero. I found myself rooting for the gang members, even when they draw their guns. Even when you fear for Ana and the cohort of women she belongs to, you may be thrilled, as I was, to discover how well their alternate universe operates. Not every scene in the novel works, but most of the book is daring and believable. –Grace Lichtenstein

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Photo by Hilary Abe

Louise Erdrich is one of those writers I had always meant to read, partly because I have long been fascinated by the American Indian culture that she inherited from her Chippewa mother, and partly because of the raves I’ve heard about her writing. But time slipped by and I never read any of her 16 novels until recently, when I turned to The Night Watchman (HarperCollins). After a two-year-long dry spell when Erdrich thought she was all written out, she came across a preserved collection of her grandfather’s letters, both personal and political, and was inspired by his life and times. At first, I saw the book as an encyclopedic account of the Chippewa in mid-twentieth century America. But then the people in the novel came to powerful life, becoming flesh-and-blood intimates, and I couldn’t put the book down. There was Thomas Wazhashk, the night watchman at a factory producing mechanical jewelry parts known as bearings, who was inspired by Erdrich’s grandfather. There was his niece Patrice (better known, to her annoyance, as Pixie because of her upturned almond eyes), who supports her mother and young brother by working at that same factory. Not to mention her suitors, Wood Mountain the boxer and Barnes the boxing coach, as well as others on their reservation. Part of the surprisingly recent history their story tells was a monumental battle to preserve a longstanding agreement the Chippewa had with the U.S. government, which the latter tried to terminate (and which they saw as “ex-terminating” their land, and them along with it). That battle was a true chapter in American history, as were several of the book’s plot elements, including a bizarre story about a “water jack” and a horrific one about the terrible fate of Patrice’s sister, Vera. You want Vera to come home safe, you want Patrice to fulfill her dream of going to college, you want the Chippewa to keep their land. And you realize how close Native Americans could come to losing their land when you read in Erdrich’s afterward that the Trump administration tried to terminate the land rights of the Wampanoag, the tribe that first welcomed the pilgrims here. –Sally Wendkos Olds