ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Review: Deciphering Al Hirschfeld

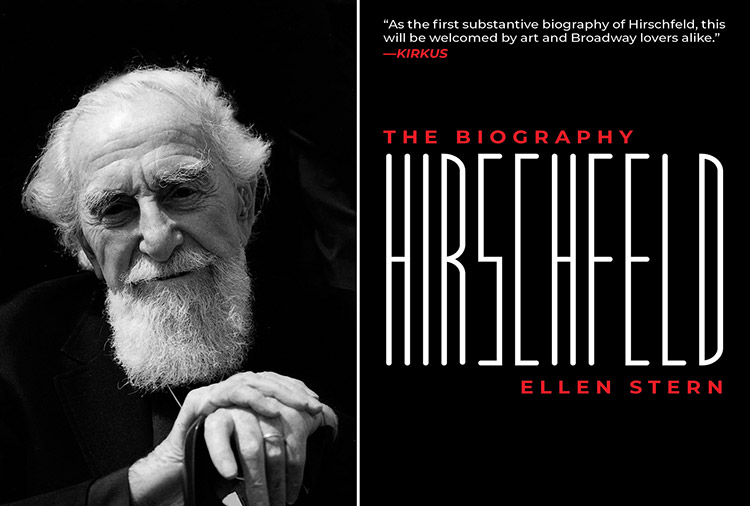

The renowned caricaturist gets his first biography

By Deborah Harkins

Portrait of Al Hirschfeld by John Mathew Smith / celebrityphotos.com

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Here’s Hirschfeld, the first biography of Al Hirschfeld, the celebrated artist whose legendary caricatures of Broadway stars riveted theatergoers for some 70 years. Over that career span (he died in 2003 at age 99), he created 10,000 pen-and-ink drawings “characterizing,” as he put it—he thought “caricature” sounds unfairly negative—everybody who was anybody in the theater world: actors and playwrights, musicians and lyricists, producers and directors, and political figures, as well. And when he started cunningly embedding his daughter’s name in his drawings for the Sunday Arts & Leisure section of The New York Times (and later for magazine illustrations and record covers), he deemed his readers’ intense searches for the hidden NINA “a national insanity.”

Hirschfeld led a dynamic life, and Ellen Stern (a NYCitywoman contributor) tells his story dynamically, adopting a jaunty present tense, so that all the events in this richly detailed book seem to be happening—or about to happen—right now.

The boy born to a working-class family in St. Louis exhibited his artistic talent early. “It never occurred to me that I could do anything else,” Stern quotes him as saying. His mother, Rebecca, moved the family to Manhattan when he was 9; he saw his first Broadway show, the musical High Jinx, by Rudolf Friml, when he was 10; he got his first job, as a brush cleaner in the art department of Goldwyn Pictures, at age 16. His talent, gregariousness, wit, and love of the theater would eventually turn him into the quintessential sophisticated New Yorker. “I could not believe the absolute glamour,” marveled Jules Feiffer after one of the twice- or thrice-weekly parties hosted by Hirschfeld at his East 95th Street townhouse. “Here is this guy who knew everybody in the world, is loved by the world, was feted by everybody, and he had half of the world to his house for dinner.”

Hirschfeld was a fabulous storyteller—emphasis on fabulous: “His stories, like his caricatures, are spun of whimsy, sass, and the perfect line,” Stern notes. And he had plenty of tales to amplify. Propelled by what a friend called his “force of life,” Hirschfeld traveled over the world several times, seeking artistic enlightenment and exotic places. He sampled the bohemian life in Paris in the 1920s. Adlai Stevenson invited him on a jaunt to see King Solomon’s Mines. He went to Morocco, Baghdad, Egypt, Tahiti. He lived for almost a year in Bali, where he found his line. “The Balinese sun seemed to bleach out all color, leaving shadows, so that things became black and white. Everything was pure line. People became line drawings walking around. I knew that my life would never be the same.”

The book (published by Skyhorse) is laced with Hirschfeld’s flavorful commentary. To Liberace’s agent, who expected to be given the original Hirschfeld drawing of the flamboyant pianist free: “I promise to dispatch, without further ado, the original painting to Mr. Liberace posthaste, without payment, of any kind, to hang in his living room…on condition that they send me Mr. Liberace to hang in mine.” Of Candid Camera host Allen Funt, who complained about Hirschfeld’s caricature of him: “I had nothing whatever to do with the way Mr. Funt looked. That was God’s work.”

Hirschfeld had a robust love life. His first wife was a former chorus girl, Florence Allyn. When she left him, he had a romantic relationship with actress Paula Laurence. His second wife, actress Dolly Haas, Nina’s mother, was the love of his life. After her death, he married wife number three, Louise Kerz, a family friend whose nurturing ways brought him out of the tailspin he had gone into at Dolly’s death.

But he was an indifferent father to the elusive Nina. Was she pleased at the fame of her name? “When asked what Nina thinks about being NINA, Hirschfeld replies, ‘I don’t know. I’ve never asked her.’”

“I was my parents’ little toy, just the little girl who played the piano,” she says now. “I do not believe I was an adult to my father.” She was a rebellious teenager, and her father and she clashed mightily throughout his life. There were times when he banned her from his home.

For much of his career, Hirschfeld drew his caricatures ensconced in a barber chair in the fourth-floor studio of the 95th Street townhouse. He worked, as all caricaturists do, from publicity photographs. He’d take off from the publicity photos, adding the idiosyncratic tics and touches he’d note on a scrap of paper in his pocket during rehearsals and out-of-town tryouts (“Brillo” for hair, “fried-eggs” for eyes, etc.) and turning the result into a Hirschfeld.

Hirschfeld continued to work until the month before his death on January 20, 2003, creating his last caricature for The New York Times—of Tommy Tune, with multiple lengthy legs. On June 23, 2003, six months after his death and three days after his 100th birthday, Al Hirschfeld got his own name in lights: the Martin Beck Theatre on West 45th Street metamorphosed into the Al Hirschfeld Theatre. (“[Impresario] Martin Beck’s granddaughter had to be persuaded to go along with the name change.”) The notables attending the ceremony included Arthur Gelb and Louise Hirschfeld, Al’s widow, who cut the ribbon, Barbara Cook, who sang “A Wonderful Guy,” and Brian Stokes Mitchell, Prince, Carol Channing (Hirschfeld’s favorite subject), Whoopi Goldberg, Arthur Miller, Kitty Carlisle, and the one and only Nina, dancing with Victor Garber as he crooned a song about a woman called Nina.

To see the book: Al Hirschfeld: The Biography. For more information, view the Al Hirschfeld Foundation website, https://www.alhirschfeldfoundation.org

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Deborah Harkins has served as a long-term editor at New York magazine, a book editor, and a freelance editor and writer for several magazines and websites, including The Modern Estate and Women’s Voices for Change.

See other stories by Deborah Harkins: