ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Our Favorite Books for November

This month we love books by and about women: Gail Collins and the coming “gerontomatriarchy,” Elaine Stritch by Alexandra Jacobs, Zadie Smith’s first short fiction collection, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, the first woman artist to document the early American republic, and Barbara Feinman Todd—a ghost writer for Hillary Clinton and others.

Still Here: The Madcap, Nervy, Singular Life of Elaine Stritch, by Alexandra Jacobs (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is for anyone who loved Stritch and dished on the hilarious hair-curling gossip that billowed around her and the colorful denizens in her world of show biz. It’s hard to picture this sassy dame as a little Catholic girl who grew up in Detroit; not surprisingly, she didn’t stay there long. At 18, Stritch followed her dreams right to New York—with occasional gigs in Hollywood and London. Bold and brassy, she was the “bad girl of Broadway” who had love affairs with men like Marlon Brando, the closeted Rock Hudson, and other stars. But despite her mouth-dropping chutzpah in public, privately she retained some of those early religious precepts, remaining a virgin till after age 30. Showered with accolades for theater, film, and TV, Stritch won four Tony nominations and three Emmy awards. In her one-woman shows, she talked about everything, including her long struggle with alcohol, the lifelong dependence that developed after her first drink at 14. Despite her great success, she said she needed two drinks before every performance. –Sally Wendkos-Olds

The Anglo-Jamaican writer Zadie Smith’s first short fiction collection, Grand Union (Penguin Press), told in a variety of styles and voices—reflecting Smith’s life switching between New York (she’s an NYU creative writing professor) and her home town, London—is a mixed bag. But it contains several masterpieces, each of which, for me, started out nonchalantly, gradually reeled me in, and ended unexpectedly, with profundity and sorrow. “Kelso Deconstructed” takes off from real events on the day in 1959 when an Antiguan carpenter in London was killed by a street marauder, the murderer’s documented alibi rendered here in verse. This story’s final sentence? ALL THE WORLD IS TEXT. Words, in other words, can be cheap. “For the King” tells of two old friends catching up at dinner in Paris. Later, in her hotel room, the narrator regrets not having found the words to describe a situation she’d witnessed that afternoon, on the train from Strasbourg (seat of the European Parliament, tellingly): A man with Tourettes kept repeating Pour le Roi! While the other passengers plugged in their ear buds, the woman accompanying him, probably his mother, continuously responded with gentle, soothing words. Now that’s communication. –Linda Dyett

Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, Ben Bradlee, First Lady Hillary Clinton…what writer wouldn’t give their eye teeth to work with these marquee names? Barbara Feinman Todd worked with them all. In her behind-the-curtain memoir, Pretend I’m Not Here (Harper Collins), a phrase she employed to put certain self-conscious interviewees at ease, she deftly and at times hilariously describes her rise from Washington Post copy aide to journalism professor and ghostwriter/book collaborator to an august group of public figures. Along the way, there were unexpected outcomes—“birthing” a village, testifying before a Senate hearing and wrestling with a devastating betrayal, whose drama harked back to a warning she had received in a totally different context, but one she considered an apt metaphor for political Washington: “Washington’s a swamp; no one gets out alive.” But, Feinman Todd more than got out alive. She reclaimed her own story, one she feared had been lost in her total absorption of others’ stories, and gifted us with this insightful record as evidence. –Arlene Hisiger

“The world’s vision of aging women had always been based, in large part, on maternity,” writes New York Times columnist Gail Collins in No Stopping Us Now: The Adventures of Older Women in American History (Little Brown), her third in a trilogy of histories of U.S. women. The inimitable Collins traces the waxing and waning of older women’s household roles, weight, earnings and related issues. Here she goes past maternity to menopause and beyond—deploying her breezy voice to reel off anecdotes about false teeth, girdles and hair coloring, quack medical advice, and the right to work late in life. Whatever you think is new in lifestyles of the not-rich older dame, it isn’t. Multigenerational households? Around since the Revolution. Teaching as a career? Traditional and poorly paid. Cosmetic surgery? Collins’s first citation is 1922. Some might damn this book with faint praise (“breezy”) but it is underwired with serious scholarship. What angers are the insults—shriveled, etc.—so often hurled once women are past their “seed pod” days. But women live longer, so demography is destiny; here’s to the coming “gerontomatriarchy.” For the record, Collins will be 74 on Nov. 25. –Grace Lichtenstein

(Above right) Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (1771–1849); Self-Portrait, ca. 1800–10; Black chalk, black ink and wash, graphite, and Conté crayon on paper; New-York Historical Society.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

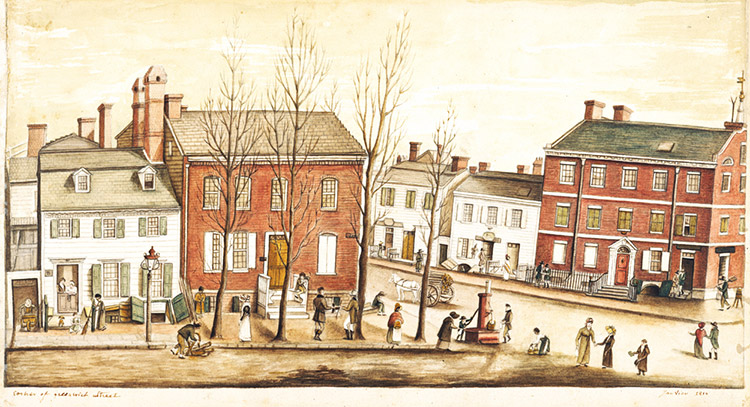

Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville (New-York Historical Society Museum & Library/D. Giles Ltd.) offers an intimate look at the United States in the early days of the republic: New York Harbor with Sandy Hook Lighthouse, 1807; a snowy day in 1809 at the corner of Warren and Greenwich Streets; Yale College in 1815; “Washington City” in 1820, with its new White House. In stunning drawings and watercolors, the young baroness records her sojourn through seven nations, including two extended stays in the U.S., first in 1807 as a refugee from Napoleonic France, and later as the celebrated wife of France’s Minister Plenipotentiary. In one, guests are welcomed at Montpelier, the estate of her close friends Dolley and James Madison; in another, 16 leaders of Plains Indian tribes present a war dance during their visit with President James Monroe. Here too are portraits: royal Osage warriors, a Seneca “Squah” and papoose, a chambermaid reading and a young girl studying diligently at École Économique, started by the Neuvilles. The baroness was, as Roberta J.M. Olson writes, “a woman of the world and ahead of her time in celebrating the differences among the people she boldly encountered.” –Suzanne Charlé

(Above) Indian War Dance for President Monroe, Washington, D.C., 1821; watercolor, graphite, black and brown ink, and gouache on paper. The “war dance” was performed at the White House during the visit of representatives of the Pawnee, Omaha, Kansa, Ottoe, and Missouri tribes. Neuville, who was in attendance, recorded the event, portraying at the left Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight), one of the five wives of half-chief Shaumonekusse (Prairie Wolf), wearing the horned headdress. In the upper background she sketched Monroe with four companions, including Baron de Neuville wearing a feathered bicorne hat.

(Above left) Peter of Buffalo, Tonawanda, New York, 1807; watercolor, graphite, black chalk, and brown and black ink with touches of gouache on paper. Neuville identifies her sitter as “Peter of Buffalo.” The word “tonaventa” refers to nearby Tonawanda, site of the Tonawanda Seneca Reservation. Neuville’s sitter has manipulated ear lobes pierced with one earring, which, like his bare feet, are traditional for Seneca tribesmen. He wears hybrid apparel: an undershirt, a fur piece, and leggings with garters, and carries a trade ax known as a halberd tomahawk, a knife, and a powder horn—as well as a string of wampum.

(Above right) Martha Church, Cook in “Ordinary” Costume, 1808–10; watercolor, graphite, black chalk, brown and black ink, and touches of white gouache on paper. The inscription identifies the sitter as a cook named Martha Church, dressed in everyday attire. Neuville endowed the subject with dignity. It is unclear whether Church was a free domestic or a slave, or whether she was of Caribbean or African descent. Many of the artist’s works demonstrate a sociological interest and celebrate work.

(Above) Corner of Greenwich Street, 1810; watercolor, graphite, and touches of black ink on paper. Greenwich Street ran perpendicular to Dey Street, where the Neuvilles lived. Nothing remains of this neighborhood, later the site of the World Trade Center. Near the cellar hatch of the brick house at the center stands an Asian man. He may be the Chinese merchant Punqua Winchong, who was in New York and Washington, and who attended one of the Neuvilles’ famous Saturday parties on March 28, 1818. This work is one of the earliest visual records of a Chinese person in the U.S.