ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

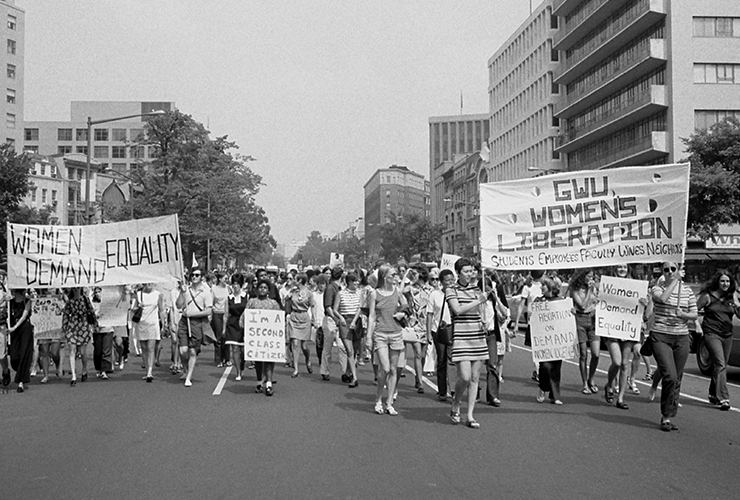

Kicking Ass in Flat-Heeled Shoes

Why late in life I became a neo-feminist.

By Nancy Weber

. . . . . . . . . . . .

“What do you mean, you’re not a feminist?” the guy across the restaurant table demanded hotly. I don’t remember his name or face—we’re talking the fall of 1968—but I remember his smug certainty. “Of course you’re a feminist.”

“I’m a humanist,” I said loftily. I was 26, a freelance writer and a semi-wild Village chick—a parody of Jules Feiffer’s parodies of girls like me. Along with everyone else I knew, I was on fire with political passions. But the women’s movement left me cold.

A big deterrent for me was—is—the feminist anti-pornography stance. The First Amendment has been my theme song since I read the stirring words in grade school. Even if it’s vile, pornography is speech and it’s protected in my book.

And I saw second-wave feminism as mostly white and middle class, a less urgent struggle than the great battle for Civil Rights. The summer of 1968, I’d jumped at an invitation to join a small cadre of journalists in Shrevesport, Louisiana, on and around the set of Slaves, the first film with a racially mixed cast to be shot in the deep south. Ossie Davis! Dionne Warwick, Stephen Boyd!

Not that I did anything to advance the cause. Scandalously naïve, overwhelmed by the local struggle for equality, I became the story, walking hand-in-hand through downtown Shreveport with a local young leader of the NAACP. Heart in right place, head out to lunch.

The Ku Klux Klan, originally okay with the production because some members were hired as extras and techies (everyone wants to be in the movies), went ballistic over my sassy stroll. They threatened to blow up the set unless the producer sent me packing.

I flew directly to the Democratic Convention in Chicago to join a merry band connected with the radical monthly Ramparts, who’d gathered to put out a daily wall sheet. We hung out with everyone colorful, from William Buckley Jr. to the Yippies and Hunter Thompson. Okay, we didn’t win Eugene McCarthy the nomination; we didn’t end the war in Vietnam. But we questioned all the givens—left, right, and center. Our mainstream colleagues envied our gadfly freedom.

And two months later, back home in New York, growing out the perm I’d gotten in a hopeless attempt to sport an Afro, I was saying to this guy whose name I don’t remember, “That’s why I’m not a feminist. It’s not my fight.”

My date gave me a squirrely look. He wasn’t giving up. “Do you believe in equal pay for equal work?”

“Yes, sure, absolutely.”

“Then you’re a feminist.”

We’d be splitting the check, in other words.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Why Feminism Is About All of Us

Equal pay for equal work. Generous maternity leave and the option of daycare centers or workplace childcare. Safe and legal abortions. I believed and believe in all these things. I just never saw them as women’s issues. They’re about all of us. About that precious, elusive liberty: to define yourself.

For every woman who is objectified and demeaned as a sex object, there’s a macho asshole locked into his role. For every reluctant full time mother and homemaker, there’s a father who envies her extra hours of knock-knock jokes with a jam-smeared three-year-old. Shuffle the structure of the day, factor in affordable support, and everyone benefits.

A pause while I put on my hardhat. Because—here goes—I think abortion is about men, too. I’m not talking about villains and victims, about pregnancy consequent to rape, incest and other forms of outright violence or cultural coercion. I’m talking about pregnancy within a relationship. I always thought the women’s movement erred—actually slowed down achievement of its abortion rights goals—by behaving as if conception came about through parthenogenesis.

Relegate men to the role of sperm donors and you can hardly expect them to be dream fathers, fully committed to the joy, hard work, and lifelong responsibility of parenthood. We need abortion rights because individual liberty trumps government control. And we must guarantee equal access for the poor and isolated. Long before Roe v. Wade, women with money and connections could nearly always find a doctor to perform a safe abortion. This isn’t a gender battle; it’s class warfare.

I’m proud of my politics, but I have to confess: I had one shameful reason for not joining the women’s movement. I personally didn’t need feminism—thought I didn’t, anyway—and that made me shortsighted about people who did.

Lucky me: My mother was a great role model. She painted professionally, played killer golf, venerated Gertrude Stein, daily dazzled my father and put family dinner on the table at 6:00 pm for the two children she lovingly raised. I assumed I could have and do it all.

For my 12th birthday I got a typewriter, a sleek Olivetti Lettera 22, in support of my passion—even then—for writing. No one in my family laughed at my certainty that I would grow up to write books, have babies, travel the world and pretty much define myself.

Joyce Engelson, brilliant editor of four of my books written in the ’70s and ’80s, once chided me: “Never base your politics on your own life.” I had done exactly that.

This past February, tuning in to the PBS three-hour special Women Who Make America, I realized how woefully I’d underestimated the need for second-wave feminism. But it wasn’t just other women who needed it. I did, too.

One of my books, The Life Swap, memorializes an adventure I had in 1973. I put an ad in The Village Voice, challenging an unknown woman to try to be me while I tried to be her. I was obsessed with the notion that by assuming another woman’s name, eating what she ate for breakfast, doing her work, and living with her lovers, I would think her thoughts and feel her feelings. And she would do the same being me.

The woman I chose as my swap-mate was a married, bisexual, polyamorous clinical psychologist and academic who ate unflavored yogurt for breakfast. Of all the challenges awaiting me, though, perhaps none was more difficult than her feminism. In the book we collaborated on after our wild attempt to get into each other’s skin, she derided me as a Barbie Doll who tottered around in painful Charles Jourdan sandals to please my male chauvinist boyfriend. I called her a prisoner of her ideology, viewing everything through the narrow lens of grim doctrinal feminism.

She woefully underappreciated the man in question, but she was right about the shoes. Corns, hammertoes, bunions: yeah, I had them all. And I was right that feminism informed every move she made. But I was wrong in thinking her own real life was grim.

I realized this only recently, after watching the PBS special. In a sound bite before the history of the movement, Hillary Clinton exclaimed, “What fun we had!” A glorious grin lit up her face.

I’m sorry that I missed the battlefield camaraderie of feminism, the unmatchable pleasure that comes of changing the givens. I had fun annoying the Klan (from my safe, white perch) and fighting to protect the First Amendment—but the sisters I refused to call sisters had fabulous fun, too. World-changing fun.

I still call myself a humanist—but maybe, is it allowed, a neo-feminist, too? There’s nothing on earth like kicking ass. Especially in flat-heeled shoes.

Nancy Weber’s novella Ad Parnassum, a mosaic-like homage to Paul Klee, has been published by Underground Voices. Her story Little Dan will appear in Between the Shores, edited by Alex Freeman and T.C. Mill for the New Smut Project (March 2015).

January 24th, 2017 at 5:48 pm

This is great — hello, fellow feminist!