ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Guilty Pleasures in Covid Time

Want to be enticed by movies again? These offerings from this year’s 59th Lincoln Center Film Festival will do it

By George Blecher

Table talk: Rebecca Hall directs Tessa Thompson, seated, left, and Ruth Negga on the set of Passing. Photo: Emily V. Aragones/Netflix

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Usually it’s a sexy affair. For a few hundred bucks, you get sneak peeks at future classics, live interviews of Beautiful People, the naughty satisfaction of being a step ahead of the crowd.

This year—the 59th iteration of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center—I went just to cheer myself up. In this second year of Covid, even compiling the list of films was a guilty pleasure—Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates.

The lines in front of the Elinor Bunin and Walter Reade Theaters were sparse. People looked a little lost. The crowds at Alice Tully Hall were livelier, but lacked sparkle. It wasn’t only because of Covid. We’re still weighted down by Trump, the catastrophes of global warming, the recent disappointments of the Biden administration: there’s not a lot of joy in the New York air. Presentations were short, few foreign directors or actors were on hand, hardly any glitz and glamour. The films themselves had to rouse us out of our lethargy.

All the films I saw kept me interested. Two or three—outstanding. Applause polite, subdued. People hurried out of the theaters. Except for one packed house, there were empty seats. I had to wonder if the responses would have been different—more cheering, more boos—if we weren’t living under a cloud.

My plan: avoid the blockbuster, superstar-studded films—Joel Coen’s Macbeth, Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, Almodovar’s Parallel Mothers; barring another Covid variation, they’d be in general release a breath after the Festival was over. Catch the Romanian films Bad Luck Banging, or Loony Porn (worst title in movie history) and Întregalde. Even though nobody seems to know or write about it, since the execution of Ceausescu in 1989 Romania has been in the midst of a cinematic New Wave comparable to France’s Nouvelle Vague of the ’60s or the Danish Dogma films of the ’90s; every Romanian film in international release has been at least interesting, several (The Death of Mr. Lazarescu; Child’s Play; Police, Adjective; Graduation among others) close to extraordinary.

Touchdown: Red Rocket director Sean Baker, holding the mic, accompanied by his cast, in a Q & A with New York Film Festival director Dennis Lim.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A must-see: Sean Baker’s Red Rocket. A 50-year-old Tisch graduate, Baker has been a quiet phenomenon for 20 years—a 21st century Cassavetes who manages to put together private financing (Florida Project) and make movies on a shoestring (Tangerine) that dig deeper than any other American director has gone.

Passing, as in passing for white, the directorial debut of Rebecca Hall, was a must-see if only for Ruth Negga, the brilliant Ethiopian-Irish actor who played Hamlet last year at BAM, is due to play Lady Macbeth on Broadway—and should have won the 2017 Best Actress Academy Award for the 2016 film Loving.

Two films I was curious about: Norwegian Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World and Panar Panahi’s Hit the Road. Trier’s first two films—Reprise and Oslo, August 31st—were terrific, the next three not so much, but this one sounded like he was back on his game. Panar Panahi is the son of Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, who manages to make totally charming films under impossible circumstances, so maybe some of the talent rubbed off.

Finally, a new print of The Round-Up (1966) by the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó. Have you heard of Jancsó? Maybe not. I saw his The Red and the White 50 years ago and never forgot it. An almost silent black and white film about the Russian Civil War, in its careful evocation of the politics of power and violence (though all the violence occurs off-screen and characters come on briefly and then disappear), it felt like a Foucaultian meditation on power, choreographed by Merce Cunningham.

A quirky list of films, but then isn’t everybody’s Festival list a Rorschach test of personal taste?

Getting ready for a grilling: Katia Pascariu as a schoolteacher under fire in Bad Luck Banging, or Loony Porn. Photo: Silviu Ghetie/Micro Film 2021

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I started with Bad Luck Banging, made under the stress of Covid—and showing it. Presented in chapters, Bad Luck is an encyclopedia of modern-day horrors situated somewhere between Dante’s Inferno and Sebald’s Rings of Saturn. The central issue concerns a married couple’s sex tape that finds its way to the internet. (And yes, the tape is shown in its vivid entirety right at the start of the film.) The wife is a respected high school teacher, and the last section of the film depicts a kangaroo court of parents who voice various predictable objections to her behavior, which she defends eloquently but no less predictably—and in the last of three alternate endings turns into Wonder Woman and ensnares all the parents in her net. To me, the most interesting section is a long walk through a nightmarish Bucharest. At first, the assumption is that the woman is simply walking through the busy city, but soon it becomes evident that she’s accompanied by a second sensibility—the camera—that keeps pointing out the sins and excesses of late-stage capitalism: abandoned buildings, crushing traffic, plastic dreck, gambling parlors, people cursing at one another. There’s a hurried, insistent quality to the camera work that feels like the anger of the 1960s, and in the middle sections are clips of violence dating from World War I to Ceausescu’s execution and beyond. Though the film didn’t quite work for me—the points are driven home with a sledgehammer—its anger may be relevant when our own city feels gutted rather than overcrowded, and we almost long for the bustle that the film condemns.

Bad Luck is also about the limitations of film. The director, Radu Jude, quotes the Perseus/Medusa myth in which Perseus can only look at the Medusa in the reflection of Athena’s shield. Jude contends that film is that once-removed reflection, the image of the horror rather than the horror itself. Pretty obvious, but at a time where many people see no difference between cell phone/computer/film/TV and “reality,” maybe Bad Luck is a necessary corrective. (Magnolia Pictures is said to be arranging for U.S. distribution of Bad Luck Banging later this year.)

Halt! Maria Popistasu as a zealous humanitarian aid worker in Întregalde.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The other Romanian film, Radu Muntean’s Întregalde (the title refers to a village in the Carpathians), is more straightforward. Like every film in the Romanian New Wave, it raises interesting moral questions, in this case what does generosity mean in a suddenly prosperous, class-divided society? A caravan of Bucharest aid workers sets out each winter to deliver packages to remote corners of a beautiful West Romanian landscape of mountains and scattered villages. One of their SUVs gets stuck in the mud on an impossible country road, and an old peasant they’re giving a lift to wanders off into the woods. One of the young women insists on bringing him back to the warmth of their car, but in searching for him jeopardizes her colleagues’ safety. And how serious are these aid workers anyway? Isn’t there more than a little paternalistic condescension in the way they appear as ersatz Santa Clauses once a year and disappear just as fast?

This is a brooding film, full of mud and cold, capturing the discomfort and helplessness that the aid workers feel in an alien landscape. It features a remarkable performance by a non-actor, Luca Sabin, as the senile, vaguely sinister peasant they go searching for. Întregalde is well-intentioned, grown up, admirably non-judgmental, but perhaps too serious for its own good. The best films in the Romanian New Wave (check out Wiki’s “Romanian New Wave” article) have more surprise, tension, higher stakes, more complicated moral choices than the relatively obvious ones in Întregalde. But whatever the film’s limitations, it typifies a national sensibility dedicated to self-searching. It’s remarkable that a whole country’s creative energy (at least in filmmaking) seems to be in making narratives that are, in David Foster Wallace’s words, “passionately moral, morally passionate.” (Întregalde’s U.S. release is awaited from Voodoo Films, its Romanian distributor.)

Two films went pretty quickly through me.

Far away from home: Mother and son, Pantea Panahiha and Rayan Sarlak, exploring a desert in Hit the Road.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A charming but bewildering first feature, Panar Panahi’s Hit the Road is an allegory of a middle class Iranian family apparently on a road trip to nowhere, or at least nowhere specific. There are ambiguous incidents. (At an obscure “border,” the older son is taken away by mask-wearing motorcyclists, never to return. Is this an oblique way of saying that he’s growing up, and that life is dangerous beyond the safety of his family? Or, as his family understands, is he a rebel taken off for execution?) The younger son (Rayan Sarlak), a precocious eight-year-old, seems to come from a stable of talkative Iranian child actors, one more expressive than the next, and fills the film’s underwritten parts with manic energy. Hit the Road pulls in two directions at once: though there is something ominous even in the landscape that the family traverses—and the father (and other men in the film) are handicapped by casts on their legs—the dangers are treated with a gentle, almost comic touch, perhaps the only way that Panahi can depict the tension between private citizens and an authoritarian government. The strongest sense we are left with is the warmth of a family that sings together, kids one another, and at one point does a riff on Kubrick’s 2001, in which father and son float together in a cartoon cosmos.

Hit the Road raises a nagging question: in Iran’s repressive society, how did this film get made, as well as those of the director’s father, Jafar Panahi (Taxi, Offside, etc.), Asghar Farhadi (A Separation), and Abbas Kiarostami (A Taste of Cherry)? They’re freer, more individual, more socially conscious than most American films. All depict an Iranian middle class with cell phones and American-made cars, issues of aging parents, class divisions, complex legal problems. In other words, people like us. What are we to make of the fact that many Iranian films depict lives more similar to those of the average American than American films do? (Kino Lorber has the U.S. rights to this film.)

On the run: Renate Reinsve in The Worst Person in the World.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I kept rooting for Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World, but it never quite took off. Trier works the territory often claimed by Eric Rohmer—the mating rituals of affluent, articulate young people. What distinguished Rohmer’s films was the way his characters talked—a blend of philosophy and pseudo-philosophy, a gentle parody of young sophisticates’ extreme self-consciousness. They always thought they knew more than they really did, yet we sensed both Rohmer’s affection for and envy of them. What he admired—and what we couldn’t help admiring too—was how young they were.

The Worst Person’s central character Julia (Renate Reinsve) is as charming as a Rohmer character, as lively—but not as smart. Her central problem is that she can’t stick with anything—not a profession (she studies to be a doctor, then a psychologist, then a photographer, and she works as a bookstore clerk and would-be writer) or a man (first a muscle man, then a cartoon artist, then a baristo). It’s a timely subject for a film, and Trier tries everything from dream and fantasy sequences to long analytic speeches by a domineering boyfriend to get into Julia’s head. But the analysis doesn’t yield much. Though she has plenty of reasons to move on (the artist thinks he knows more about her than she does, the baristo is unambitious and dull), ultimately her fickleness is troubling, not amusing.

One sequence, however, is worth the price of admission. Julia crashes a wedding and picks up a guy. They flirt like crazy—sniff each other, watch each other pee, stand as close to each other as they can without touching—all the while swearing fidelity to their absent partners. Trier doesn’t try to understand them. He just lets them be silly, daring, sexy young people in the bloom of their lives. (Neon, a film distributor, has U.S. rights for The Worst Person.)

The two best contemporary films on my list were Rebecca Hall’s Passing and Red Rocket by Sean Baker.

A woman perturbed: Ruth Negga in Passing.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I approached Passing with some reverence. An adaptation of a novel of the Harlem Renaissance finally getting its due, it’s directed by Sir Peter Hall’s daughter and features Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga, two of the most talented actors of their generation. (They’re in their late thirties.) The plot centers around two well-heeled African-American women, one of whom is married to a white man, the other to a prosperous African-American doctor and living in a Sugar Hill townhouse. Though we assume the title refers to Clare (played by Negga), who is passing for white, it applies equally to Irene, whose confined upper middle class life is also a kind of passing, and whose psychological breakdown is the true center of the film. Reviews have commented on the film’s technical excellence and modernist touches—the black and white contrasts, the 4:3 book-shaped aspect ratio cinematography, the suggestive, dreamy piano fills that meld ragtime with the turn-of-the-century avant garde composer Eric Satie. But Passing is also an homage to silent films, with long, meditative closeups of the main character that seem to call for printed dialogue to complete them.

Director Rebecca Hall’s sensibility is evident in every sequence. There’s one beautiful tableau after another, suggestive moments where the camera finds ways to hint at Irene’s disintegration—a crack in the ceiling, a disconnect between what she sees and what we see. Simply by showing Irene walking home with groceries at different seasons of the year, Hall conveys the repetitiveness and claustrophobia of this woman’s life. Yet I came away admiring more than loving Passing. It might be a question of male vs. female sensibility; the film may resonate more with women than men. But it felt a little too monotone to me, too overdetermined. There’s very little humor or surprise; in the few moments when the film lightened up, the audience sighed with relief.

Ruth Negga’s performance as Clare, the flirtatious, headstrong, racially passing woman, is breathtaking. Her character describes herself as dangerous, and that is accurate: her on-screen presence is charming, seductive, suicidal, totally alive. Judging from her performances in this film and in Loving—and her reputation in the British theatre—Negga may be the most versatile English-language actress since Cate Blanchett; anything she does is essential. (Passing arrives in select theaters on October 27th, and will stream on Netflix starting November 10th.)

Scene from a marriage: Bree Elrod and Simon Rex having it out in Red Rocket.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I thought I was the only one in the world who knew who Sean Baker was. I’d seen all six of his feature films beginning with Four Letter Words (2000), and watched him get better and better. But Alice Tully Hall was brimming with young, enthusiastic fans; here was the only showing I attended that had some of the pizzazz of the pre-Covid Film Festival. Written by Baker and Chris Bergoch, Red Rocket goes deeper than any of Baker’s previous films into a single character—in this case, an aging porno star (Simon Rex) who returns to his wife and mother-in-law in a shabby Gulf Coast town replete with oil refineries that belch pollution 24 hours a day. Rex is simply amazing. He has the strong, zipped-up look of a Gary Cooper or today’s Adam Driver, but from the second he starts begging his mother-in-law to let him in, he’s boyish, maniacally talkative, damaged, charming, completely believable. He’s in virtually every frame of this film, whose driving force is the same as in all of Baker’s films—whether it’s possible to love someone and live a decent life in awful circumstances. For Rex’s character, Mikey Saber, it really isn’t; as the actor put it succinctly in the Q and A after the film—“I want something from every one of the other characters.”

Baker’s films start slowly. We have to be content with curious characters who pop up every five minutes without a clue to what the writer and director intend to do with them. Details are salted through the film that will have significance later. Scenes that don’t seem to bear on the central issues—such as a multi-car crash that Mikey causes, flees from, and lets a young friend take the rap for—turn out to be crucial. A half hour into the film, Mikey goes into a donut shop, where he’s turned on by—falls in love with—a 17-year-old counter clerk. The girl (Suzanna Son), who calls herself Strawberry, at first seems innocent and playful, but soon proves to be as sex-obsessed as he is, and perfectly pleased to have as a boyfriend a fallen porno star twice her age. Mikey’s life is a rat’s nest of conflicting emotions: what does he really want? Does he care about anybody but himself? Can he really abandon his wife again? Is he in love with the girl, or does he just want to make money off her potential as a porno ingenue? The charm that he’s used for a thousand purposes is enlisted to titillate her, and the tragedy of the film is that it works: by the end she’s ready to go off to Hollywood with him. Finally this is the subject of Red Rocket: how people’s need to manipulate others crushes their better intentions. There may be something too damaged about Mikey Saber to see him as a tragic figure, but, goodness, is Sean Baker a gorgeously talented filmmaker! (A24 will distribute Red Rocket.)

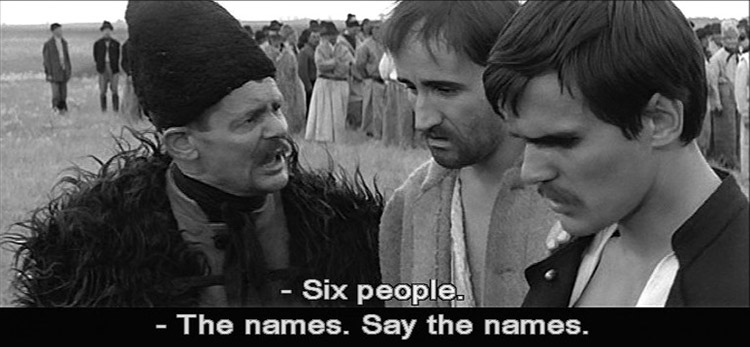

Overview: A scene from The Round-Up, filmed in a non-stop barren landscape.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Seeing Miklós Jancsó’s work after a 50-year hiatus was a bit of a shock. In the interim, films have become so formulaic and commercial, it’s hard to imagine that Jancsó was nominated five times at Cannes for Best Director, was a huge international success in the 1970s and ’80s, and received lifetime awards at both Cannes and Venice. Today, finding an American distributor for his films would be impossible; a Jancsó film is a dark experience, less like one of our frantically-paced movies than a live, slow-moving painting.

The Round-Up (1966), Jancsó’s breakthrough film, has virtually no setting: it takes place on a barren plain or field with the barest of buildings or enclosures. It’s shot in starkly contrasting black and white, as if the scenography was by Franz Kline or Piet Mondrian. The situation couldn’t be simpler: it’s the mid-19th century, and a local baron’s soldiers, having captured a group of rebellious peasants, are trying to find their leader. The action is quiet, subtle—no crying, shouting, no blows exchanged. It feels something like a living chess game. Men—almost exclusively men—move in and out of the frame taunting one another, intimidating one another, humiliating one another. But there is almost no overt violence, and even when there is—as when a young woman is forced to run a gauntlet of switches—there is no accompanying sound, which makes her torture even more horrific. This is power stripped down to its essentials—people with guns dominating those who don’t have them. Rather than having a proper plot, the film is a process, a slow unfolding. Many of the takes go on for minutes. Characterization is kept to a minimum—one character is exceptionally brave, another a turncoat. By the end of the film, I, for one, felt drugged; by watching and marveling at the choreography of sheer power, I felt like I’d participated in it.

Seeing a Jancsó film every 10-20 years would probably be enough; these films linger a long time in one’s innards. But a half century seemed too long to wait. They’re master classes in filmmaking: by stripping away many of the tools of conventional narrative, Jancsó turned some of the worst aspects of human nature into terrifying ballets that we can’t look away from.

When I saw the film, the 140-seat Beale auditorium at the Elinor Bunin Theater was far from full. What audience there was had to be filmgoers like me, who had seen one of his films and never forgotten it. I didn’t see any new films at the New York Festival this year as indelible as The Round-Up (which, while not stream-able, is available as a DVD on Amazon), but maybe Covid itself will inspire filmmakers to dig as deeply into human behavior as Jancsó did 55 years ago.

Desperate men in The Round-Up.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

George Blecher writes for The New York Times and for a number of European publications about American politics and culture. This year, he is a fellow at CUNY Graduate Center’s Writers’ Institute. See georgeblecher.com