ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

First Aid, Italian Style

An unexpected solution saves escapees from NYC a trip to the hospital in Tuscany

By Maddine Insalaco

The artist couple Maddine Insalaco and Joe Vinson posing during one of the landscape painting classes they teach—this one in Civita Castellana, Italy.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Back in July, as the Covid crisis was tapering down in our home town, New York, my husband Joe Vinson and I left town for our annual migration to Italy. The two of us are artists and teach landscape painting classes mostly in the Tuscan countryside—and mostly to visiting Americans. Having weathered the worst of the lockdown while the city struggled to control the coronavirus, our return to the farming village where we have lived for six months every year since 2002 was a welcome deliverance.

In normal times, I would have seamlessly slipped back into rural existence, picking up rhythms and routines exactly as I had left them six months before. I would not have given the slightest thought to the world I had just left behind, the reality of which faded away the closer we got to our alternate home. This year though, in a Covid-transformed universe with no work and no routine to resume, I was in reflection mode.

The national responses to the pandemic in Italy versus the United States were in stark contrast. Starting in early March, Italy, a federation of twenty regions, went into a severe lockdown for almost three months. Apart from authorized workers, all Italians were obliged to stay home and not venture more than two hundred twenty yards from their residences except to buy groceries. Heavy fines were imposed for violations. Such draconian measures paid off with the rapid flattening of the contagion curve, the orderly reopening of the economy, and the return to normal life, which began in May. In America, the absence of a national policy at the federal level obliged the individual states, many with opposing attitudes to the virus, to respond separately with mixed and chaotic results.

I felt really good to be a New Yorker in that moment, but I suffered for my country as a whole. I found myself thinking a lot about the differences between American and Italian cultures. I became a more sensitive observer of the world around me, anxious for examples to illustrate the divergent approaches to life’s events and challenges.

M. Insalaco, “New Vineyard from the Pieve di Piana,” oil on canvas, 18 cm x 19 cm, 2020. Students painting during a class in Murlo, Tuscany.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Following a kitchen accident, one such example unexpectedly presented itself at our front door.

One night cleaning up after a dinner party at our fourth floor apartment in the historic center of Buonconvento, outside Siena, a wine glass broke in Joe’s hand. A panicked cry issued forth from this otherwise quiet and reserved person, who was now rocking back and forth in pain as blood spewed from his hand. The cut was deep and clearly needed stitches, but it was after 1 a.m., and we had no appetite for the forty-minute drive to the hospital in Siena. We did not consider the Covid risk, as there had been so few cases in the province. The urgency of the situation helped me summon the resolve to improvise a bandage from cleaning rags to stop the bleeding. The idea was to make a temporary fix and deal with it in the morning.

The next day, I made calls to four friends, explained the situation, and asked for advice. The unanimous recommendation was to go to the emergency room, the Pronto Soccorso. But as we readied ourselves to forfeit the day to traveling and waiting for help, one friend called back and told me about another option she had forgotten about. Apparently there is a man in the village, a retired health care worker, a general medical fix-it guy, who deals with problems like ours. She was willing to call him to describe the situation and offered to give me his number to set up an appointment. Curious and reluctant to spend hours at the hospital, I acceded.

Minutes later, I connected to the hurried voice of Libero (a name meaning “free” or “available”), who was busy with something outside of town but willing to stop by when he returned.

“You mean you will come to our home?”, I asked incredulously.

“Of course!” he responded. Reacting as if a house call was completely normal, I gave him our address, and waited for the doorbell to ring.

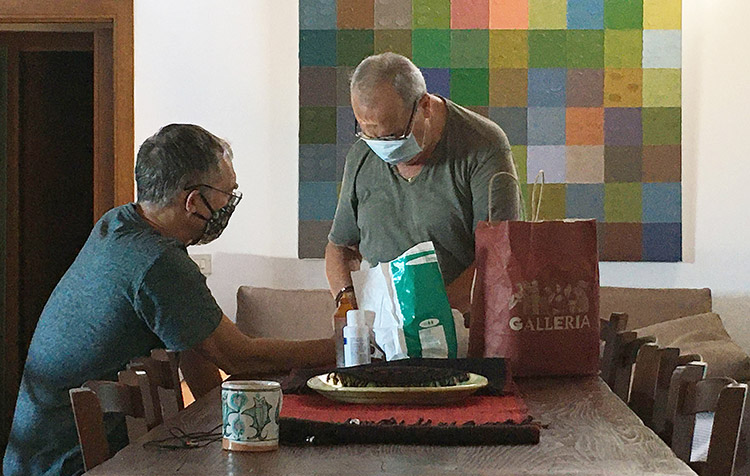

“Why is it that most of my house calls involve walking up so many stairs?” So exclaimed the voice of the yet unseen Libero as he struggled up the steps to our top floor apartment. The balding and masked figure who presented himself was winded from the climb. Sweat was seeping through his shirt. He carried two shopping bags full of supplies. Uninterested in small talk, he entered our home at a determined pace, serious and focused on the job at hand. Literally.

Libero treating Joe Vinson at home in Buonconvento.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

He sat my husband down at the dining table, asked for a towel, rummaged through his bags, and proceeded to take out three bottles of various liquids. He examined my pathetic bandaging job with disdain as he prepared to remove it.

I became nervous, realizing that I had no idea about the credentials of this man who, in his inexplicable haste, was about to inflict pain upon my husband.

“Libero, so…are you a doctor?” That was the question I timidly asked, hoping for some insight into his background.

“Oh no, but I was an emergency room nurse in the Siena hospital for forty years. I’ve seen everything.” he replied. With that, I felt as reassured as I could be in the moment.

Examining the injured hand, Libero admitted that the cut was deep, but that fortunately there was no tendon damage. It would be a simple fix. He proceeded with an aggressive disinfectant routine, splashing liquids to and fro while my husband writhed in agony for a few very tense seconds. He then broke open two small vials of a special glue, spread it on each side of the cut, and pressed them together. Searching the room, he spotted some newspaper by the fireplace and grabbed a piece to fan the glue. It dried instantly.

“It’s perfect.” he declared, “You don’t have do anything more. It will heal by itself, and the glue will fall off in a week. Keep it dry, and don’t bump it.”

We sat in amazement. All of ten minutes had passed since he entered our home.

The charge for this service was 150 euros, about $175—cash only. I knew by Italian standards that this was very expensive, even though in New York it would have been considered a good deal. I tried not to react, but my face must have betrayed my true feelings about the price.

“You don’t have to spend anything else,” he stated sheepishly. “If there are any problems, I will come back right away. Call me any time.” We paid him and apologized for living on the top floor—and he left.

Coming from the United States, where the most minimal medical service costs a fortune, we considered ourselves lucky to have paid so little to resolve our problem. Moreover, we were thrilled not to have spent the better part of the day sitting in a hospital emergency room, even though that service would have been free. As expected, each of the Italians with whom I shared this story exclaimed that the price was too high. Clearly as foreigners we were not given a local price. This irked me.

So five days later, when the glue fell off my husband’s hand early and it seemed like the cut was more open than it should have been, I didn’t hesitate to call Libero and ask him to take another look. As promised, he returned shortly after my call, complaining once again about the stairs.

“Signora, its perfect,” he said. “There is nothing wrong here. This is exactly as it should be.” He led us over to the window and pointed to the dried pale extremes of the cut that showed it was healing correctly. We spent a few minutes on small but pleasant conversation. By the time he reached the door, the mood was decidedly friendly. I joked that it was better that he visited us here than in our previous home—which had twelve more steps to climb. He agreed, and we said our goodbyes.

Scattered students during a Fundamentals landscape painting class in Buonconvento, Tuscany.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I have never lived in a small or rural American town, so I cannot say that similar situations do not occur there. However, I did live in Rome for ten years, where all kinds of useful services were routinely performed by retirees in the so-called black economy (not unlike the black market)—involving transactions that are unofficial, undocumented, and probably illegal.

These services all are conducted outside formal institutional channels and rely on simple trust built up through a network of satisfied parties. They are the product of one of the most defining features of Italian culture, the so-called Fantasia Italiana, or Creative Imagination, applied to the expeditious solution of human problems great and small.

Reflecting on how we would have dealt with an analogous drama in New York, I know that we would have gone to a doctor or hospital, and would have rejected alternate solutions, if there were any, outright. It was this cultural position that caused us to hesitate when presented with the possibility of help from a self-appointed medicine man. Having lived here for years, though, we’d learned to embrace local realities.

Had there been no option but the hospital, I would have felt completely confident about what we would have experienced in terms of assistance and cost. Italy has universal health care, and while the physical structures in which services are delivered are rather drab, the technology used is generally state of the art and the doctors are as knowledgeable as they are anywhere else. The real difference coming from the U.S. is the price tag. Medical services as well as pharmaceuticals are available at a fraction of the American equivalents. Had we been obliged to pay for my husband’s hand to be stitched up in a non-emergency situation, the price would have been about Euro 50 ($60). We are not part of the health care system here but never hesitate to go to a doctor when we have a problem—because it‘s affordable.

Within days, my husband’s hand was healed enough to use normally again. Cost aside, we felt that we had discovered something good in Libero. He happened to share that his specialty is catheters, for which, considering his speedy and aggressive style, we felt more than relieved to have no present, and hopefully future, need.

M. Insalaco, “Ripolina Vineyard Late Afternoon,” oil on canvas, 19 cm x 26 cm, 2020.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Maddine Insalaco is a painter who divides her life between New York and Tuscany, where she organizes landscape painting workshops and gastronomic tours with her artist husband. An authority in the field of early open air painting, she has published, lectured, and curated museum exhibitions on related subjects in the USA and Italy. Instagram: @maddine_insalaco.