ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Confessions of an Absent Sister

Involving pain, bewilderment, and an overdue reunion at a psychiatric hospital in Oregon

By Deborah Kasdan

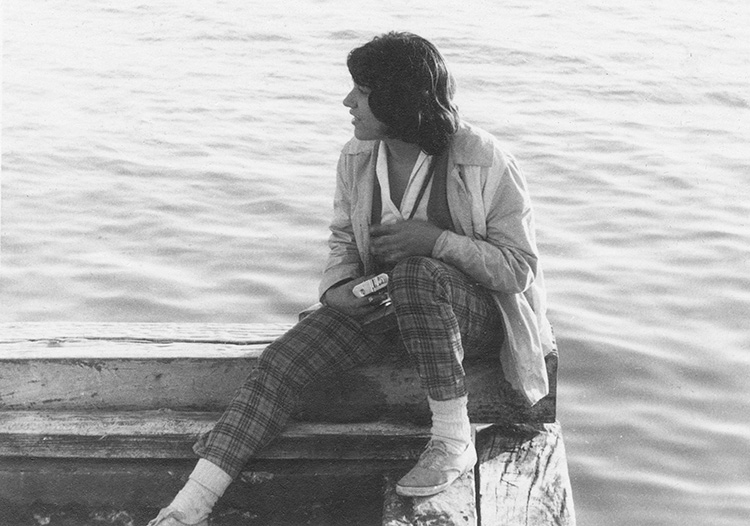

Rachel Goodman on a trip to Israel after graduating from high school, 1961.

The article you’re about to read is the second in our offbeat series, Before the Ink Dries: excerpts from yet-to-appear-in-print fiction and nonfiction manuscripts by NYCitywoman contributors. Here is a chapter from Deborah Kasdan’s Roll Back the World: A Sister’s Memoir, to be published in October 2023 by She Writes Press. It tells the story of two sisters. One, the author, has a corporate writing career in the New York area. The other, with a poetic nature, is a long-term patient at a psychiatric hospital in Pendleton, Washington. They reunite during a fraught cross-country visit.

The article you’re about to read is the second in our offbeat series, Before the Ink Dries: excerpts from yet-to-appear-in-print fiction and nonfiction manuscripts by NYCitywoman contributors. Here is a chapter from Deborah Kasdan’s Roll Back the World: A Sister’s Memoir, to be published in October 2023 by She Writes Press. It tells the story of two sisters. One, the author, has a corporate writing career in the New York area. The other, with a poetic nature, is a long-term patient at a psychiatric hospital in Pendleton, Washington. They reunite during a fraught cross-country visit.

Nov. 29, 2022

Brilliant orange rays blanketed the cloud-tipped peaks of the Cascade Range, engulfing the puddle hopper that was flying me from Portland to Pendleton, Oregon—across the country from where I lived. For the entire hour of that trip, I kept my face pressed against the window, to soak up the view of sunset across the mountains. I was so immersed in the sky that I almost forgot I was on my way to see my sister, a long-term patient at Eastern Oregon Psychiatric Center.

Somehow, I had never managed to visit Rachel since she moved to the Pacific Northwest seven years earlier, in 1979. She was now forty-three years old, three years older than me. Rachel had been diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was twenty-two and we were living in St. Louis. She ended up so far from home as the result of a well-meaning but naive plan by her three younger siblings to free her from the dismaying treatment she received at St. Louis State Hospital. For 15 years, she had been medicated into a state of permanent sedation, and intermittently discharged to boarding houses where she was assaulted, even raped. My brother proposed that Rachel come live with him in Seattle, where he had set down roots after college. My younger sister and I, after much research and soul-searching, agreed to support his plan.

Before long, however, the two of them fought and parted ways. Rachel took off to Oregon and ended up hospitalized, again and again—far from St. Louis.

Rachel at a Pendleton, Oregon diner, on day-leave from Eastern Oregon Psychiatric Center, 1987.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Once she’d been relocated, but before being transferred to Pendleton, Rachel was out on her own, with no address. That left me feeling uneasy, unable to make plans, not knowing where she would be or when I should go. But as soon as I learned I would be attending a business meeting in Redmond—on the Microsoft campus—right outside Seattle, I knew. Here was an opportunity to do the right thing. Gut-wrenching as it felt, the time had come for me to visit my sister. I booked a side trip to Pendleton.

The year was 1987, when CD-ROMs were the shiny new thing, and the meetings in Redmond centered on emerging multimedia. These discussions—imagine being able to access an entire encyclopedia or an interactive game on a single disc!—were welcome distractions from my worry about my long-delayed meeting with Rachel.

Except for one quick trip she made to our father’s funeral six years earlier, Rachel and I hadn’t once met face to face since she left St. Louis. I phoned her from my new hometown—Norwalk, Connecticut—and sent her packages. That was it. During all those years, I mothered two daughters through adolescence and launched a career writing for trade publications.

I enjoyed learning how different industries worked, especially as I’d grown up exposed almost exclusively to professionals and academics. A social worker, my father planned cultural and social programs for Jewish community organizations. My mother held administrative positions at Washington University. For me, the corporate world was a refreshing change. But despite my career achievements, I sometimes felt disconnected from it. In my mind, earnings, market share, and other benchmarks executives worried about paled in comparison to what my family faced, dealing with Rachel. I was happy to stick with writing articles and brochures—or, as now, planning a conference program. What’s more, I hadn’t ever been able to manage Rachel’s situation and never felt, outside of my own household and raising my own children that I was a take-charge kind of person.

After cycling back and forth between Dammasch State Hospital, near Portland, and Oregon State Hospital in Salem, Rachel was in her second year in Pendleton. Mixed into those cycles had been boarding houses and group homes, where she was always too disruptive to remain. She often went off on her own, camping out and drinking wine with homeless friends. Eventually, she would get into trouble and be re-committed—especially when the weather turned cold and she needed a warm place to stay. From what I now understood, though, Rachel was staying put in the Pendleton facility. She was not being discharged, and she wasn’t running away. I figured she was too worn down to live like the footloose poet she had dreamed of being.

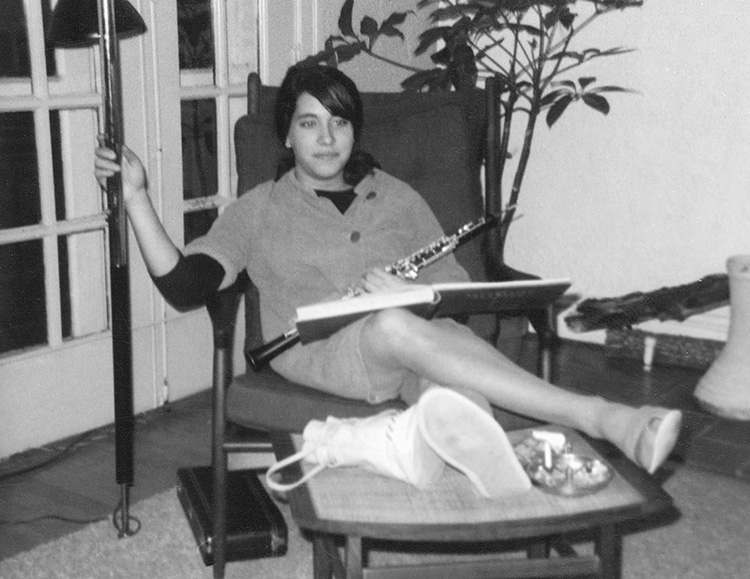

Rachel, with oboe and cigarette, at home in St Louis during her return from a gap year, 1962.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

I didn’t expect Rachel to receive much in the way of treatment or protection from the hospital system. I knew my sister well enough to recognize that she was too proud and stubborn to submit to its programs. But I also knew she needed a place to go when the outside world became too difficult for her. And that I would never be able—or willing—to offer my own home as a refuge. Visiting her meant I would have to look her in the eye and admit that no matter how much I loved her, I couldn’t help her. Maybe that’s the real reason it was so hard for me to go and see her.

Finally, however, I found the strength I needed. Maybe my work gave me confidence. If I could manage to put together a conference to introduce an obscure new technology, I could manage to see my sister. I felt good about my decision. Now, during the plane ride from Portland, a new feeling of excitement overtook my fear. In Pendleton, I checked into a motel on a high plateau—so high it appeared to be nestled within the dome of the sky. It glowed over a dusty earth covered with tundra and wild grass. as far as I could see. The sky seemed to hug me, infuse me with its glow, as though reassuring me I could now do what I had put off for too many years.

Below, near the town, loomed the massive brick hospital. Later that day, as I waited for Rachel to meet me in the front hall, I felt chills chasing away all that warmth of the big sky. I must have been too frozen by dread to put down many memory traces. I mainly recall my longstanding fear: that rage and humiliation hidden behind her unyielding eyes would rain down on me, condemning me for brutal acts of abandonment.

But that didn’t happen. Her affect was flat—from medication or the illness or both. But I do think Rachel was happy to see me. I could see she was glad that I checked her out of the hospital for day trips.

Rachel accompanies the author on piano, during a family songfest, 1962.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

“We went to the rodeo,” she told me as we drove downtown. With whom and when, I wanted to know? But she mumbled sentences that were unintelligible, and I couldn’t get any more details from her. Pendleton was famous for its wool blankets, but I hadn’t yet heard about any rodeo roundup shows. Eventually I got the picture: groups of hospital patients were taken there on outings. One small bright spot in this dreary existence.

As I looked for a parking spot in town, Rachel pointed to an intersection with rundown stores and a bar. “The Indians come here,” she said, her speech thick and slurred. It took me a while to accept her words as fact, not delusion. I finally realized Pendleton did indeed have a visible Native American population; many were indigent. I felt foolish for doubting what she told me.

She led me briskly through the local streets. “I need to buy cigarettes,” she said and directed me to a variety store. I bought her Camels. Unfiltered. She lit up and blew off a fleck of tobacco from her lip.

In downtown Pendleton, with its faded Old West storefronts and streets, the reality of Rachel emerged, lifting the film of fear that clouded my senses. Yes, she had strands of gray in her hair. Yes, teeth were missing. But as always, she stood straight, taller than me. Her shoulders, always so reminiscent of our Cleveland grandmother, presided over her imposing belly.

We walked into a dimly lit store filled with jewelry, wood carvings, and small appliances.

“Can I buy you something?” I asked her, hoping for any demand I could satisfy. “Do you need a portable radio?” I was remembering her frequent requests from her hospital days in St. Louis. She shook her head no.

We examined the jewelry stand. A strand of beads, with wood, colored glass, and twisted threads, caught her attention. I watched her touch the beads, her fingertips so much more tapered than mine. These were the fingers I had watched as a child dancing across our piano keyboard, turning the pages of her books, holding her pen, or lifting a fork in the air as she argued her points at the dinner table.

I paid for the beads, expecting her to wear them now. But she put them away in her drawstring purse. I hoped she wouldn’t trade the beads or give them away; I wanted her to keep them as a souvenir of my visit.

Rachel (left), with the author and their brother, during a brief family residence in Boston, 1950.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The next morning, instead of taking Rachel out first thing, I met with a psychiatrist who’d asked to speak with me. In his gray, windowless office, he told me that Rachel kept climbing into other women’s beds at night, molesting them. I had an uncomfortable feeling he expected me to do something about it. Talk to her, maybe, and tell her this behavior had to stop? That was ridiculous; she would shoo me away in a minute. Or was he asking me what to do about this frustrating situation? Equally bizarre. What could I possibly tell him about how to manage his patient, even if she was my sister. I fumbled through the rest of the meeting and left as quickly as I could, too distraught to remember anything else he said.

My third and last day in Pendleton, I took Rachel to a diner for lunch. She consumed a sandwich and a Pepsi with vigor; I was glad to see her happy there. But when she stood up from the red vinyl bench to leave, I saw a big wet spot on the seat of her brown pants. Now I understood why the nurse at the hospital had mentioned that Rachel refused to wear paper underwear. She’d become incontinent. While I cringed in embarrassment, Rachel acted oblivious. With her back and shoulders set square, her head held high, she marched out of the diner, wet bottom and all. She seemed to be far beyond caring what anyone thought about the way she looked or smelled.

Only in her writing did Rachel expose her desolation and pain:

I fly, I scream, I gnash, I cry out in pain and bewilderment. I want out!

I see the skies and dream like a rodent does in the slick of the night.

I eat lonely in the daytime, lonely at night, and I walk out with my nose up in the Aire, and cry and scream in pathetique.

“I turn my back to Rachel.” The author, home from college, and Rachel on a weekend stay from the hospital. Painting by Rachel’s high school friend Gary Tenenbaum, circa 1967.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Before her transfer to Pendleton, Rachel had sent me manuscripts on ruled yellow paper, for safekeeping. Her handwriting was hard to make out, and the confessional stories I was able to decipher were disturbing. She’d clearly been off her meds and in hobo mode, camping in the woods, with occasional refuge in a Salvation Army shelter.

In a note accompanying a batch of her stories, Rachel asked me about my own writing. Send me something of yours, she said; I want to read it. But I had always written for commerce. How could I explain the fact that I never wrote from my heart, the way she did? I didn’t believe I could, even if I wanted to. Rachel was the poet in the family. And for all the years she was alive, I needed to keep our spheres distinct and separate. While she took flight, all lyrical and fantastical, I stuck to business. She wouldn’t have been interested in what I wrote, I told myself. I absorbed myself in my work but wasn’t passionate about it. My work occupied only my head. Though I knew the idea made no sense, part of me feared that writing about the feelings in my heart might make me crazy. Crazy like Rachel.

Author’s Note:

Rachel died suddenly in January 2003, of pneumonia, in Eugene, Oregon. She lived in her own home by then, with assistance from a local mental health agency. I saw her several times there, including a visit shortly before her death. Knowing that Rachel never blamed me for what happened to her, I eventually learned to forgive myself for being largely absent from her adult life—and to thank her for breathing life into my writing journey.

Deborah Kasdan retired in 2014 from a 35-year corporate career writing about business and technology. Her book, Roll Back the World: A Sister’s Memoir, will be published by She Writes Press in October 2023.