ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Coming of Age in the Years Preceding Roe

What price personal autonomy? Remembering the days when abortions were illegal

By Roberta Hershenson

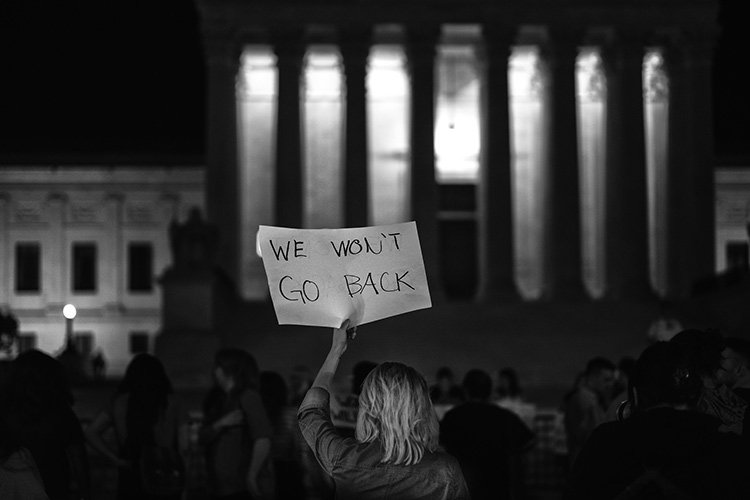

Fighting for abortion rights—in 2022—in front of the Supreme Court on the day the draft opinion for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was leaked. Photo: Miki Jourdan.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

MAY 9, 2022

Overturning Roe v. Wade would have far-reaching consequences, not only for women, but for everyone. Those of us who came of age before the 1973 Supreme Court decision—as I did—can testify first-hand and vividly to the harmful effects caused by the fear of an unwanted pregnancy. A late period made us distraught; we shuddered to think of dropping out of high school or college to have a child. With no recourse except an expensive, illegal backroom abortion that most of us could not afford, we envisioned our lives ending and a new, encumbered one beginning. Many lives did end from botched abortions. The fear of pregnancy cast a shadow over our bodies and crippled our psyches.

When pre-boomers and older boomers came of age, abortions were illegal and women died after using metal hangers and other desperate means to end their pregnancies. Those who could afford the high prices took secret trips to Puerto Rico or had abortions in unsavory conditions—at the peril of the practitioner’s arrest, the woman’s future sterility, or even her death. These familiar stories still haunt me today.

Less often discussed are the pervasive, corrosive effects on families when abortion is not a sanctioned option. Parents struggling to provide for their children lose the legal right to limit their family size—a personal choice if there ever was one. Budding careers are cut short when women drop out due to an unplanned pregnancy. Fear of a teenage pregnancy warps the relationship between parents and daughters, who become partners in a twisted dance of do’s and don’ts. The worst thing a girl could do to her family before Roe was to become pregnant. A girl was taught to be “good,” meaning non-sexual. Her most passionate advisor was likely her own mother, who had endured her own unwed-pregnancy fears, born of her mother’s fears, and her mother’s before that.

A young girl before Roe was instructed to keep her body virginal until marriage, when pregnancy would be not only sanctioned but welcomed. The boys she dated knew vaguely to be careful. Condoms were available, under lock and key at drugstores—but many boys did not view an accidental pregnancy as their problem. Sexuality was a taboo subject, learned surreptitiously from books or from the misconceptions of other kids. But Marilyn Monroe was out there in the 1950s, oozing sexuality. Pointy torpedo bras were displayed in store windows, and taboos heated up the erotic atmosphere. Sex happened, as sex will always do.

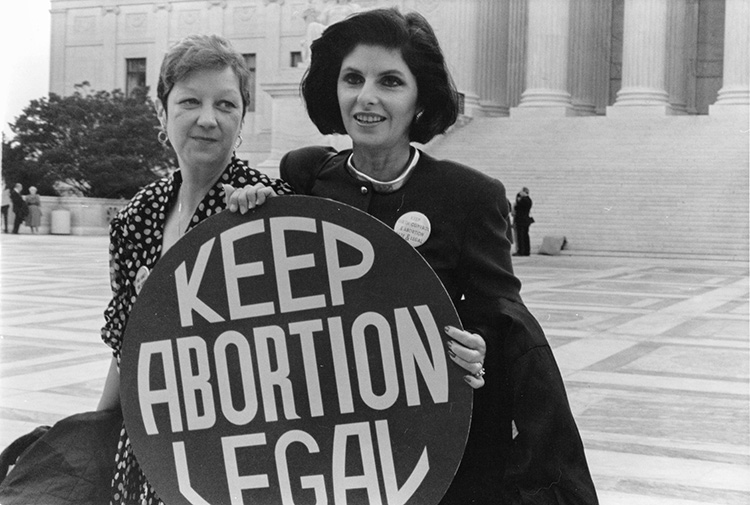

Norma McCorvey, left, whose pseudonym was Jane Roe in the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, with her attorney, Gloria Allred, outside the Supreme Court in April 1989, where the Court heard arguments in a case that could have overturned the Roe decision. Photo: Lorie Shaull.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

A jumble of social and religious values prevented parents from providing birth control to their teenage daughters and sons. Fear was the most potent birth control method, but it wasn’t always effective. Pregnant teens married early to avoid stigma, or were accused of becoming pregnant on purpose to “trap” a boy into marriage. Girls were sent away to have their babies, shame was heaped upon shame, and normal sexual impulses were vilified with all the hypocrisy their elders could muster.

When young women got married, the virginal and non-virginal alike walked the aisle in a white dress and veil, presenting the veneer of purity their parents required. On her wedding night, a girl had permission to release all that was supposed to have been withheld. Suddenly she could engage wholeheartedly in the lovemaking previously forbidden. But the “on” switch did not always work. Confusion reigned in the bedroom, marital sex could be dysfunctional, and couples flocked to therapy or got divorced. Their parents were baffled; where were the grandchildren to bounce on their knees? Babies were okay now! Why so much neurosis and unhappiness?

Them v. Us. Photo: Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

When sex is fraught with fear, boys are damaged too. In 1961, as if gearing up for the sexual revolution and youth quake looming a few years ahead, the movie “Splendor in the Grass” laid out the problem, poignantly depicting the broken hearts of two teenagers, played by Warren Beatty and Natalie Wood. She is sexually tormented, he is confused, and their relationship ends in a tumultuous breakup. Wood’s character is so guilt-ridden about sex—wanting it and fearing it—that she lands in a mental hospital.

A legal abortion is not a panacea. A potential life will not develop; there may be feelings of sadness or guilt. The choice to abort may be difficult or liberating, but it will be the woman’s choice. She is the one who will carry that fetus for nine months, the one who will ensure the baby is loved after birth. How does a coerced birth help that child to thrive? Or its parents, or society? I doubt the Supreme Court has a satisfying answer to that question.

Roberta Hershenson is an arts journalist whose features, profiles, and news stories have appeared in The New York Times and other publications.