ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

A Misbegotten Macbeth Descends on Broadway

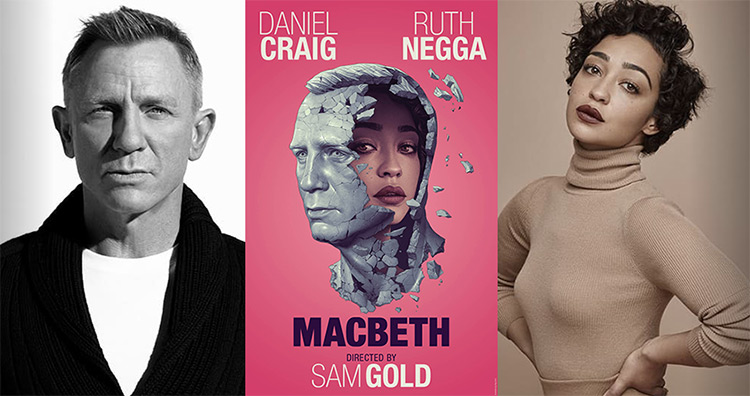

The knives are out in this scathing review of the Sam Gold production starring Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga

By George Blecher

APRIL 28, 2022

This is how I imagine director Sam Gold addressing his cast at the first table read of the Macbeth production that officially opened at the Longacre Theater for a six-week engagement on April 28: “Guys, instead of ‘acting’”—here a disdainful frown and heavy air quotes—“I want you to be yourselves. Actually, be less than yourselves. Be dumbed-down versions of yourselves, as if you were performing in a high school production, just for the credit. Instead of allowing the musicality of Shakespeare’s language to come through, street-talk your lines in whatever your native accents happen to be—Welsh, Irish, Bronx, Boston Southie, it’s all good.

“Be sure to play against type. Duncan, instead of acting like a king whose assassination would shake a kingdom, be a fat, beer-drinking lout whose death would be a great relief to everyone. Malcolm, Duncan’s son and future leader of the kingdom, drag out your lines in the sleepiest way possible so that no one could imagine you leading even a troop of ushers picking up discarded programs after the show.

“And you, Lady M. We know you’re a talented actor, famous for immersing yourself in your roles. This time, lighten up. Do a kittenish thing once in a while, rant and rave a bit, but no chemistry at all between you and Mac. No touching, no interesting body movements, don’t even look at anybody, act like you’re in a completely different play. In the ‘Out damn’d spot’ scene, we’ll stage it mostly in the dark so the audience won’t even see you.

“James Bond, my man! Since at least some of your admirers will come mainly to see your bod, we’ll keep the T- and body shirts. But no intelligence, no depth of character, OK? Rather than being inwardly tortured in the soliloquies, be cranky like an eighth grader who can’t solve a geometry problem. We’ll give you a fight scene at the end, but no swords; wrestling’s much sexier than sword play.

“Last but coolest! Witches! Instead of pretending to cook up a potion, I want you to actually scrape carrots and chop up spinach—at the edge of the stage, before the curtain even goes up! Cook a veggie soup during the play, and serve it to the cast members as they slump, exhausted and embarrassed, on stage at the end of the show. Julia Childs meets the Bard! So cool!”

A 2021 streaming rendition. Joel Coen’s Tragedy of Macbeth starred Denzel Washington, above, and Frances McDormand. Photo, A24.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Granted, Macbeth is a fiendishly difficult play to get right. It’s short, dark, spare, and feels more like an Icelandic saga than any other Shakespearian tragedy. Everyone from Orson Welles to Paul Scofield to Denzel Washington has tried it here in the States—reportedly with mixed results.

But I’m afraid the production with Craig and Negga really is bad. (I saw it at a preview performance, but suspect it didn’t get much better by opening night.) Superstars or not, exorbitantly priced tickets notwithstanding, a man in our row was snoring five minutes after the opening curtain, and half the row didn’t return after the intermission. More than one groan or cry of exasperation could be heard in the stunned silences, and in the midst of a particularly tedious scene someone cried out, “BORR-ING!” At the end, a dutiful New York audience gave the performers the perfunctory standing ovation, but it might have been because they felt lucky to have paid only preview prices instead of even more inflated sums once the play officially opens.

In a way, this misguided production—complete with normcore-inflected street duds for costumes and thrift-shop sofas for scenery—does leave the audience with a rather Shakespearean question: Has it really come to just this? Have eloquence, pageant, subtlety completely fled the scene?

A 1971 film version. Roman Polanski’s Vietnam-era Macbeth featured Jon Finch and Francesca Annis.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

For years, the Off-Off-Broadway director Richard Maxwell recruited non-actors to move like zombies and deliver their lines in uninflected, emotionless voices. It was a curious gimmick that tried to create tension, at least temporarily, by undercutting the audience’s expectations of what theater was supposed to be, and shocking them into really looking and listening to what was before them. Gold’s approach appears to be similar, but rather than saying the words without inflection, his players underscore every important word, as in that first painful high school encounter with Romeo and Juliet where you underlined every other word in your book to convince yourself you understood what they were talking about.

Another teacher or director might have said instead: “Kids, don’t worry about the meaning. Sing the words rather than say them. Let the sounds and rhythms of the verse take over. You’ll be surprised. The meaning might very well become clear.”

A personal example. When I was 10, I went to a progressive camp where even the youngest kids did Shakespeare. I was charged to deliver Thisbe’s speech when she discovers the dead Pyramus in the comic-skit-within-a-play of A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream.

Asleep, my love?

What, dead, my dove?

O Pyramus, arise!

Speak, speak! Quite dumb?

Dead, dead! Etc.

Not exactly Shakespeare’s most sophisticated speech, but scary for a 10-year-old.

Luckily my counselor said the right thing, and I sang the sounds at the top of my lungs. The words practically told me what to do—grab Pyramus and shake him, then drop his head in terror! The side-by-side stressed accents of “Quite dumb” made the pun brilliantly clear: Pyramus was stupid, silent and dead! The meter told me all that.

A 1936 stage production. “The Play That Electrified Harlem,” also known as “Voodoo Macbeth”, was set in Haiti with a largely amateur all-Black cast. A young Orson Welles adapted and directed. It played to sellout crowds at the Lafayette Theater. Photo WPA Federal Theatre.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

In the name of modernity, how did we get so dumb in all senses of the word? How did we lose our love of language and decide to make everything prosaic? For decades, Marshall McLuhan and others warned us that words were being replaced by images. Emails, texting, TikTok sacrificed eloquence for brevity. Technological and advertising jargon made words flat and predictable, sideswiping our sense of irony. The spare language of contemporary American fiction, the paper-thin characters of popular movies, the predictable jokes of sitcoms, diminishing attention spans—these are just a few of the possible reasons for the demise of language. A production like Mr. Gold’s has the insidious effect of making the audience feel guilty about longing for musicality and elevated diction; it suggests that to be truly politically correct, we have to accept the odd conceit that “real” people are bland and inarticulate.

But wait! What about Hair’s charming adaptation of Hamlet’s What a piece of work is man? What about hip hop? Language rediscovered! Words adored!

Even if the subject matter of rap music at times seems repetitive and the rhymes audaciously farfetched, language is the clay that hip hop is made of. In its relentlessly iambic rhythms and pounding syncopation, it often sounds like a combination of Cole Porter (“flying up high/with some guy/in the sky/is my i-/dea of nothing to do”) and the very same Bill Shakespeare who had Hamlet’s Polonius offer the hip hop-like insight that a good acting troupe can be “tragical, comical, historical, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral”—in short, any- and everything the actors are capable of.

Unfortunately, this production of Macbeth isn’t any of these things. On the contrary, it suggests that in 2022 we’ve run out of ideas, fresh ways of looking at classic texts, and that underneath the celebrity and expensive tickets, we’re still high school kids trying in vain to make sense of a dead language. Not a very hopeful view of ourselves—and, despite the communal veggie soup, not a very appetizing one either.

George Blecher writes for The New York Times and for a number of European publications about American politics and culture. This year, he is a fellow at the CUNY Graduate Center’s Writers’ Institute. See georgeblecher.com