ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

A Celluloid Visionary Gets His Due

But it’s complicated. The Jewish Museum’s exhibit of Jonas Mekas’s films has caused controversy

By Roberta Hershenson

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

MAY 26, 2022

As I watched the assorted footage presented in the Jewish Museum’s exhibit Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, I often found myself on the brink of tears. You don’t see many films like Mekas’s these days—“diary” films as natural as breathing, with fleeting images that seem both familiar and distant. His filmed memories evoke our own, too—of a life we had, or wish we had, or think we ought to have had—reminding us to treasure each passing moment, as he seemed to do. (Full disclosure: the exhibit reminded me of my own experiences making short films back in the ’80s.)

Mekas, who died at age 96 in 2019, was a poet in his native Lithuania, taking up filmmaking after arriving in New York in 1949 and immersing himself in our postwar culture. He is revered as the godfather of American avant garde cinema, with his now-familiar techniques such as shaky, out-of-focus footage; non-linear imagery; and the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated visual subjects filmed in black and white and faded color.

Mekas is not only known for his oeuvre of 93 films and hundreds of digital videos, but also for his prodigious output as a writer and promoter of the New American Cinema—a movement of non-Hollywood or anti-Hollywood films focused on independent and experimental filmmaking. He was also The Village Voice’s first film critic, his tenure there running from 1958–1975, and, in 1969, co-founded the still-vital Anthology Film Archives, in Manhattan’s East Village.

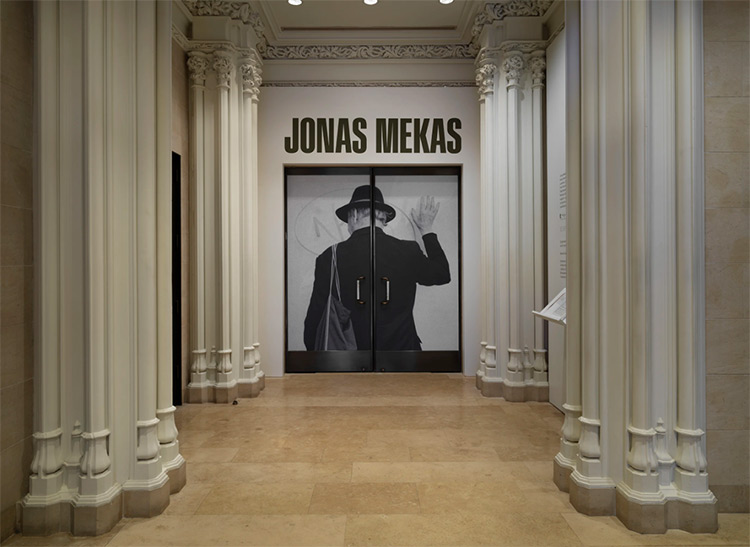

All images are installation views of Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running at the Jewish Museum, NY, February 18-June 5, 2022. Photo by Dario Lasagni.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

He influenced such filmmakers as Jim Jarmusch, John Waters, and Mike Figgis; Andy Warhol is said to have begun making films after hanging around with Mekas and his wide-ranging group of friends in Mekas’s Brooklyn loft.

Timed to coincide with Mekas’s centenary birthday year, the exhibit has stirred up controversy in its final weeks. (It closes June 5.) The historian Michael Casper, currently a postdoctoral associate at Yale’s Judaic Studies Program, whose doctoral dissertation was on the Jews of Lithuania from 1914–1940, has criticized the museum for not addressing the question of Mekas’s activities during World War II, when, Casper noted, the non-Jewish Mekas was involved in publications that promoted Nazi propaganda in occupied Lithuania. The country was a center of European Jewish culture until most of its Jews were slaughtered during the Holocaust. Casper does not directly accuse Mekas of anti-Semitism, nor does anyone else I’ve come across, but he argues that Mekas blurred details of his past to suggest he was a Jew or a Holocaust survivor.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Casper wrote about Mekas in a June 7, 2018 article in the New York Review of Books; his latest piece on the subject appeared in the magazine Jewish Currents on April 21, 2022. Other venues have chimed in, as well, including the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, a gathering place for international Jewish news, and The Times of Israel.

Daniela Stigh, a museum spokeswoman, said in a statement that Casper had not presented evidence supporting his claims, and that “the Jewish Museum stands behind the artist’s telling of his own life story in presenting an exhibition of his cinematic work.”

My complaint is somewhat different; it is with the museum’s wall text, which raises distracting questions without answering them. For instance, an introduction states that Mekas was “forced to flee” Lithuania in 1944, then segues to the fact he spent the next five years in a Nazi work camp and in German displaced persons camps. Visitors may wonder, as I did, why he had to flee if he was not Jewish. But the museum, oddly, has nothing to say about that. Nor does it explain why a non-Jewish artist is the subject of a retrospective unconnected to Judaism, except to imply a parallel between Mekas’s dislocation experiences, as reflected in his films, and those of Jewish refugees. A weekly series of art films Mekas presented at the Jewish Museum from 1968–1970 apparently made him one of the family.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Despite the omissions, The Camera Was Always Running, organized by guest curator Kelly Taxter, is worth viewing. The films, shortened from their original running time, are shown on a dozen freestanding screens placed at angles throughout a darkened gallery. True to Mekas’s non-linear approach to filmmaking, footage from various pieces of films plays at once, or the same film appears in different sequences, adding up the total viewing time to three hours. Viewers can walk right up to the screens, catch the films on a stroll through the gallery, or watch from benches.

The show’s title comes from Mekas’s own description of his approach. “I was there, I was just a passerby seeing it all with my camera. And I recorded it. I recorded it all.”

The films have titles like “Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol, 1990,” “This side of Paradise: Fragments of an Unfinished Biography, 1999” (featuring footage Mekas shot of Jackie Kennedy and her children in 1972), and “As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, 2000.” Mekas was moved by nature, beauty, and the intensity of the moment. As images passed through his conscious mind and provoked his unconscious, he captured them, first on 16-millimeter film with his Bolex camera, and after 2000 on digital video. They might be trees blowing in the wind, a circle of middle-aged people dancing in a field, or a small child playing a violin. He worked on his last film, the 2019 “Requiem,” set partly to Verdi’s score, until late on the night before he died.

Toby Talbot, a nonagenarian who co-owned the legendary New Yorker Theater with her husband Dan (and later co-owned Lincoln Plaza Cinema with him), said she knew Mekas and his brother, Adolphus, as two of “the young cinephiles who hung around the theater” in the 1960s, when cutting edge films from around the world were screened there. In a NYCitywoman interview, she recalled conversations with the brothers that were “cinematic,” not touching on their lives during the Nazi or Soviet occupation of Lithuania.

“I think they didn’t speak about it,” she said. “It wasn’t a point for discussion.”

But Jonas Mekas did engage in lively interviews and discussions that can be found in the exhibit and on the Internet. In lieu of solid information about his war years, viewers, and readers, can draw their own conclusions.

Roberta Hershenson is an arts journalist and photographer whose features, profiles, and news stories have appeared in The New York Times and other publications.