ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Seven Jews Hidden in Hitler’s Berlin

Interviewing three survivors and writing their incredible story, “Survival in the Shadows,” was for me a life-changing experience.

By Barbara Lovenheim

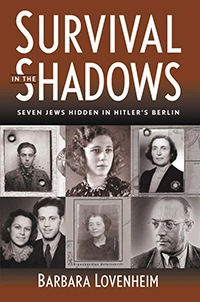

Clockwise: Erich Arndt, Ellen Lewinsky, Charlotte Lewinsky, Dr. Arthur Arndt, Lena Arndt, Ruth and Bruno Gumpel.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

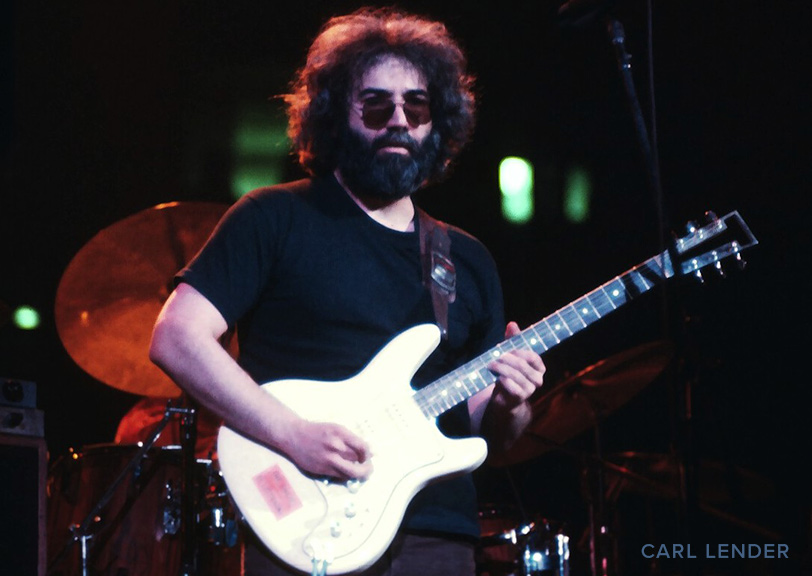

As we gather this month to observe Yom Hashoah, the Day of Remembrance for the six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust, I remember three German Jews, Ellen and Erich Arndt and Ruth Arndt Gumpel who, against all odds, managed to survive the war with four other family members, hidden in a small factory in Berlin less than two miles from Hitler’s Bunker.

Quite by chance I met Ellen and Erich fifteen years ago in my hometown, Rochester, New York, introduced by Barbara Appelbaum, a college friend who was the head of CHAI, a center that educates the community about the Holocaust. Barbara asked me to edit a book with her about survivors in Rochester. My first reaction was “No.” I knew nothing about the Holocaust except for the gruesome images I had seen of the camps and I did not think I had the stomach to deal with the issue.

But Barbara persisted and I finally agreed to meet Ellen and Erich Arndt who lived in a pleasant apartment in a Rochester suburb. I still recall our first meeting: The Arndts were seated on a couch. Ellen, a slender woman with short gray hair, was dressed smartly in slacks and a shirt. On her lap she was holding her newest grandchild. Erich, dressed in chinos and a plaid shirt, sat by her side. A small terrier bounded around the room. The Arndts were a handsome couple and as soon as we began talking, I was intrigued by their thick German accents, their warm and embracing manner, their charm, and their irreverent sense of humor. After an hour of chatter during which they touched upon some of their close escapes during the war and their futile attempts to find a writer who would document their incredible tale, I was hooked. How could I pass up the opportunity? But we were all cautious. The Arndts had been disappointed by a top writer who, after several months of research, mysteriously disappeared. I knew how challenging it would be to document their story and convey it in a convincing and readable style. I also feared my ability to deal with situations that involved brutality and torture. Although I had written many articles for top newspapers and magazines, I had never taken on a subject this difficult.

But after several meetings we decided to give it a try. By this time I had basic information about the group and their first year in hiding: Ellen; her mother, Charlotte; Erich and his older sister, Ruth, were all working as slave laborers in 1942 when Erich heard a rumor in the Jewish underground at Siemens, the giant company that was manufacturing weapons and other artillery for the war: Goebbels was about to arrest all Jewish slave laborers and send them to Auschwitz.

As soon as Erich heard this rumor he tried to persuade his father to go into hiding. Ruth and Ellen agreed with the plan. But Erich’s father, Arthur Arndt, was a distinguished doctor and a decorated World War I veteran. He was sure that the Reich would recover. And he did not believe the rumors that Jews were dying in work camps. So he resisted the plan, vehemently and steadily. But Erich persisted. “If we go to the camps we will probably die,” Erich challenged. “Maybe not right away, but soon.” Erich brought up the subject every day for weeks, and his father’s response was always the same: “Nein, nein, nein.” Finally Dr. Arndt agreed to ask his non-Jewish patients if they would hide the families. The most proactive were laborers Max and Anni Gehre and Max Kohler, a factory owner and pacifist who despised Hitler. The Gehres insisted upon hiding Dr. Arndt in their apartment; Anni would find hiding places for the others. Max Kohler then hired Erich as a journeyman to work and live incognito in his small factory.

By the time the Germans raided major factories and arrested thousands of Jewish laborers on February 27, 1943, all members of the group were in hiding. But the hunt for Jews continued. “We have failed to lay our hands on about 4,000 Jews,” Goebbels wrote in his diary. “They are now wandering about Berlin without homes, are not registered with police and are naturally quite a public danger. I ordered the police, the Wehrmacht and the Party to do everything possible to round these Jews up as quickly as possible.”

During the next two years, hiding places became scarce as many Germans were bombed out of their own homes; others were frightened of hiding Jews. Bruno Gumpel, a school friend of Erich’s, whose mother and father were sent to Auschwitz, managed to find Erich and Max hired him as a laborer to work alongside Erich. Eventually, Max’s factory was a refuge for everyone but Dr. Arndt, who remained with the Gehres. “If the Germans are going to kill me for hiding one Jew,” said Max, “they might as well kill me for hiding six Jews.”

A year after we began working together, Erich and Ellen invited me to travel to Berlin with them. There I met Erich’s sister, Ruth, who had met Bruno in hiding and married him after the war. Ruth had traveled from California to meet us. We spent days traversing Berlin, looking at the factory where they had lived in hiding—it is now a loft for architects—as well as the location of other buildings where they had worked or lived for varying periods of time. In the evenings we would gather in a hotel room, where we would talk about various episodes. Sometimes Ellen and Ruth would disagree heatedly about minor details—who carried the pea soup from the Gehre’s to the factory? Or major ones: Why did Dr. Arndt give a cyanide pill to Erich and not Ruth before they went into hiding?

It was, of course, enjoyable for them to recall episodes that were frightening at the time—but humorous in retrospect. For a few weeks Ellen’s mother Charlotte shared the apartment of a prostitute located on the same street where Eichmann had an office. (Charlotte slept days and walked streets at night when her roommate entertained soldiers.) Ellen scrubbed floors for two sisters who had been Dr. Arndt’s patients. Lena (Dr. Arndt’s wife) hid in the country with her former housekeeper, and, for a short time, Ruth and Ellen worked for Herr Wehlen, a German officer and black marketer, who entertained soldiers with elaborate dinners. More than once, he protected Ruth and Ellen from his lecherous guests.

As easy as it was to talk about these episodes that turned out well, it was extremely difficult for any of them to talk about the death of friends and family or the death of innocent Germans. Oddly enough, Erich was the most visibly sensitive; he would walk onto the patio of his apartment and smoke a cigarette when he recalled an Allied bombing raid that buried a number of German schoolchildren. He and Bruno tried to rescue the children, but they couldn’t.

During this trip to Berlin, Ellen introduced me to a German historian, Barbara Schieb, who now runs a small museum that archives material about hidden Jews. Barbara worked with me via computer to authenticate everything from the street names and routes that members of the group used to transverse Berlin to the exact dates of major Allied bombing raids. As I dug deeper and deeper into the details of the war and the Arndts’ story, I was at various times overcome by the enormity of my task and the material I was uncovering: How roughly 6,000 Jewish Germans managed to survive the atrocities of Nazism by living day to day in a shadowy underworld without identity cards, food ration books, secure accommodations, or money. It was a story that totally upset all my preconceptions that Jews passively went to the camps: Instead this was a story of tremendous courage, resilience, and resourcefulness in the darkest days of Hitler’s rule.

When the book was published in England and Germany in 2002, we premiered the book in London and Berlin to standing-room-only audiences. In the U.S. CHAI reissued the book and we all promoted the book in our respective communities. For Ellen, Erich, and Ruth the book was a highlight in their lives, giving them a new sense of pride and self-worth, an affirmation that future generations would learn from their struggles and triumph. As Ellen used to say, “living well is the best revenge.” They have all passed away now, but I cannot believe they are gone because, deep in my being, they are still very much alive. It is only once in a lifetime that a journalist stumbles onto such a story, and I am grateful that I was given the opportunity to relate their incredible journey. I hope that it will educate and move others as it moved me.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

SURVIVAL IN THE SHADOWS

Survival in the Shadows by Barbara Lovenheim

Survival in the Shadows by Barbara Lovenheim

Open Road, April 15, 2015; Kindle $9.99, Nook $10.49 and other e-book outlets. Available as hardcover $25; and softcover $12 at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other bookstores.

Print publishers: Peter Owen (London) 2002; Siedler Verlag (Berlin) 2002; CHAI (US) 2002.

The remarkable true story of two families that survived against all odds in the heart of the Nazi capital.

Reviews:

“The courage of the protectors renews one’s faith in the survival of altruism and integrity.” —The London Sunday Times

“At times deeply moving, the book shows in a compelling way the variety of attitudes that Germans had toward the Jews and presents dramatic counter-testimony to those who would paint a one-dimensional picture.” —Michael Berenbaum, former director of research, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“Skillfully blends the voices of the survivors with historical information and moral reflection.” —Jewish Book World

“An astonishing tale of lives lived in the lion’s den.” —The Jewish Chronicle

Harrowing stories of courage under devastating circumstances—this book honors the human spirit in showing real acts of heroism.” —Andrea Dworkin

“An extraordinary book, skillfully written, about seven ordinary Jews trapped in the belly of the Nazi beast. This must-read narrative sheds light on the all too rare mystery of goodness.” —Alan L. Berger, chair of Holocaust studies, Florida Atlantic University

“A gripping read, suspenseful as it is meaningful and moving.” —Pamela Katz, author of The Partnership: Brecht and Weill; screenwriter of the film Hannah Arendt.

“A celebration of the human spirit triumphing over unimaginable evil.” —Lorraine Diehl, author of “Over Here”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Lovenheim, founding editor of NYCitywoman.com, has written on lifestyle and the arts for The New York Times, New York, The Wall Street Journal, and many major magazines. She is the author of Survival in the Shadows: Seven Jews Hidden in Berlin and other books.