ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Katharine Hepburn: Rebel Chic

“Skirts are hopeless. Anytime I hear a man say he prefers a woman in a skirt, I say, ‘Try one. Try a skirt.’”

By Barbara Lovenheim

It seems improbable for a new slant on Katharine Hepburn to emerge, but the five excellent essays in the Skira/Rizzoli book Katharine Hepburn: Rebel Chic are provocative and eye-opening. Contrary to Hepburn’s public image as an indifferent fashion rebel who wore slacks in public years before pant suits came into vogue, Hepburn cultivated her counter-culture image deliberately and with great precision when she became aware of its publicity value, eventually ordering custom-made slacks and shoes and, on the sly, ordering handmade French lingerie.

“I think you should pretend you don’t care,” she once remarked to Garbo, who captivated Hollywood with her mannish suits, hats, and Ferragamo flat-heeled shoes. “But it’s the most outrageous pretense. I bet it takes us longer to look as if we hadn’t made any effort than it does someone else to come in beautifully dressed.’”

Adolph Menjou and Katharine Hepburn in Morning Glory, 1933.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A Closet Full of Gowns

During the 1980’s I interviewed Hepburn four times at her Manhattan townhouse on East 49th Street (see Interviewing Kate the Great) for The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and McCalls, each time to promote a new Hepburn film or book. Whatever the occasion and however impromptu my other visits, Kate was always wearing khaki pants, a black or white turtleneck with either a red vest, a red sweater draped over her shoulders, or a neutral-colored short-sleeved linen jacket, and clogs or loafers. She wore minimal lipstick and her face was always natural-looking, as though she had no make-up on it; her grey hair was always wound loosely around her head, held in place by invisible pins.

After one lengthy interview I remained to do picture research while Kate left for her routine weekend trip to her family’s country home in Fenwick, Connecticut. By this time I had established a friendly relationship with Norah, Hepburn’s good-natured Irish-born cook. After finishing my work, Norah offered to show me the top two floors of the house. When we arrived on the third floor, she opened a closet filled to the brim with Hepburn’s favorite costumes from six stage productions and twenty-one films. I was surprised to find this because Hepburn had never struck me as a person who would form an attachment to clothes, particularly the elaborate gowns she had worn in many films and stage plays. As I peered through the collection, I asked Norah to pull out a gown from The Philadelphia Story, one of my favorite films. In the small adjacent room, I spied a single bed lined with about half a dozen pairs of khaki slacks; on the floor were several pairs of loafers, all of which I presumed were laid out so Hepburn could grab them quickly in the morning.

In the early ’90s, Hepburn retired to Fenwick and the costumes from her closet were inventoried and packed; after she died in 2003, they were donated per her instructions to the Kent State University Museum in Ohio that has a first-rate costume collection. It is this collection of costumes that formed the basis of an exhibit that ran in 2012, which also had many outfits from her everyday wardrobe, photo stills from her movies, and publicity photos.

Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in Woman of the Year, 1942.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Arrogant and Angular

There is no arguing that Hepburn eventually became a fashion icon for dressing publicly in slacks and big, loose shirts when most Hollywood stars would not consider allowing photographers to snap their pictures unless they were wearing obvious make-up, form-fitting sweaters and dresses, and heels. But Hepburn was slim and leggy, with an 18” waist, and she grew up in an unconventional household: Her mother Katharine Houghton was an early suffragette who encouraged her six children to talk and debate openly about contemporary issues; her father Thomas Hepburn was a respected MD and advocate for women’s reproductive rights. Kate was the middle child of three brothers and, as a young girl, she tried to keep up with them by climbing trees and playing ball; at one point she was so intent on fitting in that she lopped off her hair and called herself “Jimmy.” (Her two sisters were born years later.) It didn’t take long for the young Kate to discover that pants were more comfortable than skirts, adjusting more easily to her lean torso and long legs and certainly more suitable for running and sports. So, as she matured, she continued wearing trousers and shirts, particularly to studio rehearsals, where she had to spend the greater part of the day sitting around. But she didn’t cultivate this iconoclastic image with any particular agenda; comfort to her was paramount.

“I wore pants when they weren’t fashionable; I sat down on the curb if I was tired; I did what I wanted and what I thought was reasonable so long as I didn’t hurt anyone,” she told me in one of our interviews. “But is that so unusual?

Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, David Wayne and Eve March in Adam’s Rib, 1949; Costume designed for Hepburn in Adam’s Rib, by Walter Plunkett.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Obviously it was unusual during the 1930s and ’40s, when most women wore constricting girdles, garter belts, stockings, and belted dresses. Hepburn, tall, slender, and not exactly buxom, was just not suitable for roles that required actresses who were busty and blonde, submissive to men, and rarely confrontational, and in the early years of her career she confounded the public with her arrogant posture and unconventional dress code of casual slacks, oversized shirts, and scruffy loafers.

“I realized long ago that skirts are hopeless,” she told Calvin Klein. “Anytime I hear a man say he prefers a woman in a skirt, I say, ‘Try one. Try a skirt.’”

Although wearing pants in public was not conventional, it was not frowned upon on film sets. Dorothy Arzner, well-known and popular, directed Hepburn in Christopher Strong, an early movie. “She wore pants. So did I,” recalls Kate in her memoir Me. “We had a good time working together.” In her early films and plays, Hepburn also became increasingly involved with her onstage wardrobe, working happily with designers like Walter Plunkett, who designed costumes for eleven of her black and white films. But after a series of film flops in the late 1930’s, she cancelled her contract with RKO and struck out on her own, buying the stage rights for The Philadelphia Story from Philip Barry in 1940. Free now from studio restrictions, she began hiring her own designers and recruited Valentina, an expensive Russian-born fashion couturier who had previously designed clothes for Katharine Cornell, Greta Garbo, the Vanderbilts, and the Whitneys. The Philadelphia Story—and its costumes—were a great success and Valentina became one of Hepburn’s favorite designers; she worked with Hepburn on several succeeding films and Hepburn also commissioned her to create gowns for her personal use. According to Hepburn’s niece, Katharine Houghton, who co-starred in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, if her aunt really liked an outfit that she wore in a film or play, she would often commission one for her own personal use.

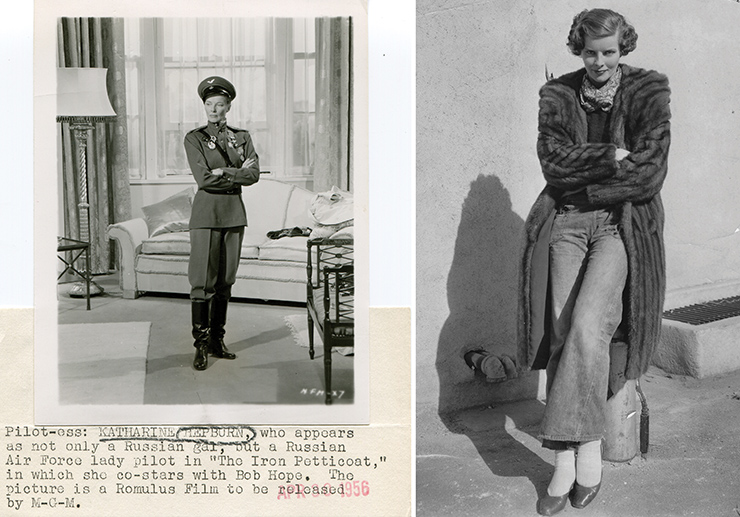

Hepburn in The Iron Petticoat, 1956; and on the RKO lot, 1932.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

As Hepburn became more successful, she took an increasingly active role in designing costumes for herself and also cast members, drawing sketches carefully on paper accompanied by very specific notes. When inspired, she would do careful historical research for period films. After seeing the first sketch for a costume she was to wear as a Russian pilot in The Iron Petticoat (1956) co-starring Bob Hope, she wrote: “Getting out of the plane and when you first see her—I visualize a very bulky used jacket and interesting costume which could make him not know if she is male or female—helmet—gloves—long coat—coveralls—but with personal touches to give individuality. . . she would never fly in what you sent me.”

She also fostered ongoing relationships with several designers. “One does not design for Miss Hepburn,” said Edith Head, who did her costumes for The Rainmaker in 1956 and Rooster Cogburn in 1975. “One designs with her. She’s a real professional, and she has very definite feelings about what things are right for her, whether it has to do with costumes, scripts, or her entire lifestyle.” As Hepburn herself summed up: “I take a tremendous amount of care over my costumes. I’ll stand longer over a fitting than anybody. But you can’t judge someone by what he’s wearing. It’s the inner part that counts.”

All Hepburn quotes except those from the author’s personal interviews are in the companion book Katharine Hepburn: Rebel Chic (Skira/Rizzoli) 2012.

Hepburn and Fred MacMurray in Alice Adams, 1935. Hepburn as Babbie in The Little Minister, 1934.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Lovenheim, founding editor of NYCitywoman.com, has written on lifestyle and the arts for The New York Times, New York, The Wall Street Journal, and many major magazines. She is the author of Survival in the Shadows: Seven Jews Hidden in Berlin and other books.