ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

My Vietnam War—Part 1

Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1966, the author—a budding New York opera director—avoided combat … and ponders his good fortune half a century later

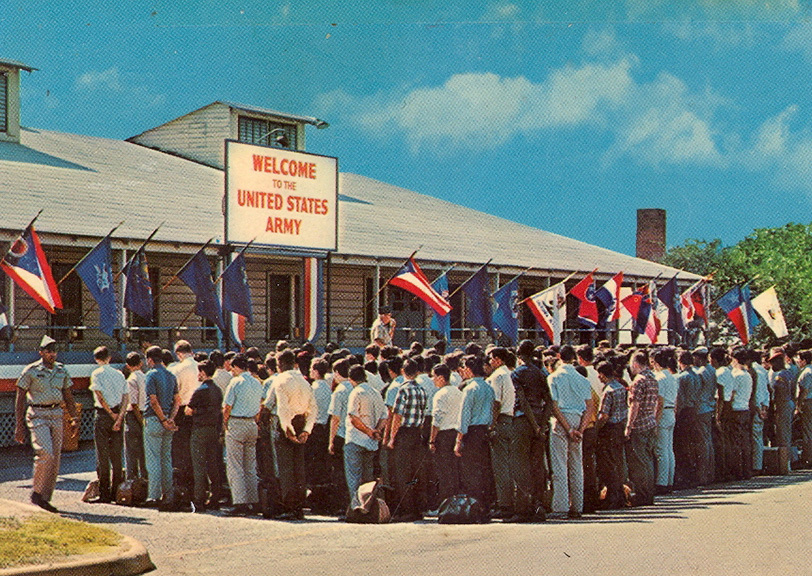

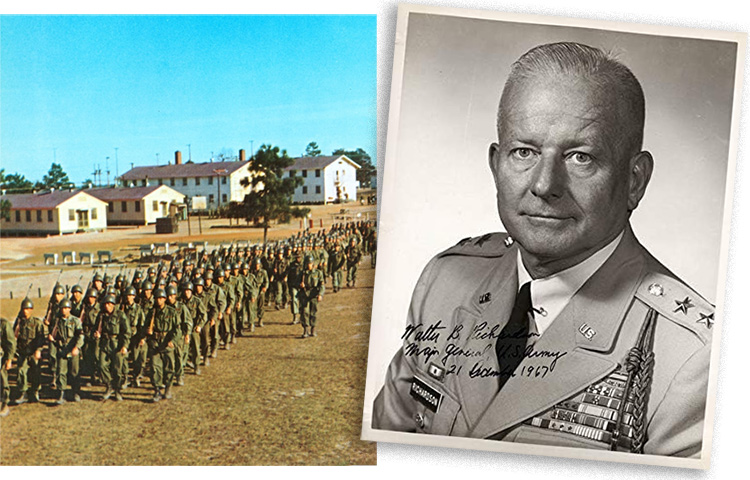

You’re in the Army now. Fort Gordon, Augusta, Georgia; Major General Walter B. Richardson.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

My Vietnam War, 1966–1968, Article no. 1 in a series

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

December 3, 2025

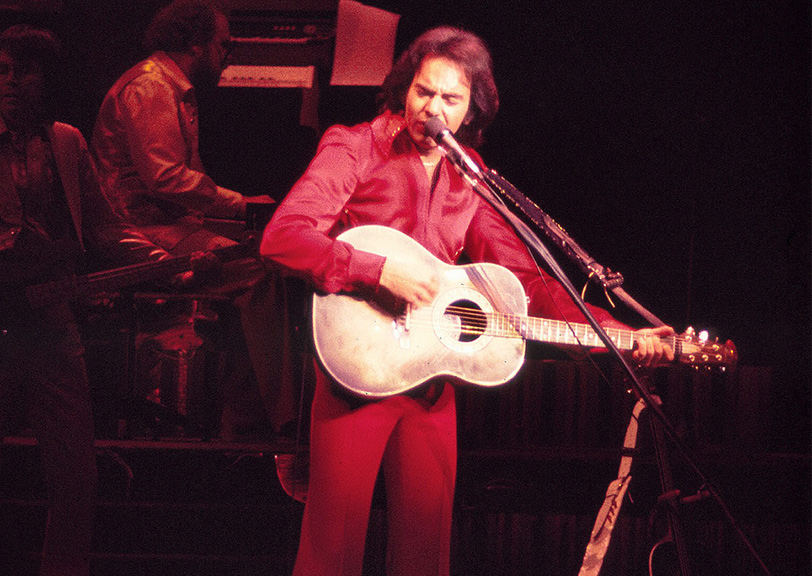

I had things easy when I served in the Army at the height of the Vietnam War. The year was 1966 when I was assigned to the entertainment division of Special Services in Fort Gordon, a training camp outside Augusta, Georgia. My duties on base were so light and my commanding officer so accommodating that I was able to spend much of my time working on projects that advanced the operatic career I’d already embarked on back home in New York after graduating from Harvard in 1961.

Grateful as I am for my good fortune, it makes me uneasy. I vehemently opposed the Vietnam War, which I found cruel, senseless, and doomed. I marched against it, voted against it, screamed against it. I considered myself first and foremost a man of conscience and firmly anti-war, especially in the case of Vietnam.

In those turbulent, divisive days, young draftees did have an escape hatch. Both Canada and Sweden offered safe haven to Americans fleeing military service.

My best friend from college, Richard Mackler, took advantage of that. A brilliant doctor and a vehement opponent of the war, he flew to Montreal prior to his deployment in Vietnam and lived there for the rest of his long and productive life. America’s loss was Canada’s gain.

Richard’s actions impressed me as brave and consequent. But I couldn’t follow his lead. I was a rising star in the world of opera. I’d already created major productions in New York, the center of American operatic activity, with more on the way. How could I give up that burgeoning career to start from scratch in another country? How could I be sure that the highly nationalistic opera circles in Sweden or Canada would welcome a young foreigner who crashed into their orbit and wanted their jobs?

Furthermore, even though I found the war in Vietnam a horrible absurdity, the United States had been exceptionally good to me and my family. Decades earlier, my maternal grandparents had escaped czarist Ukraine and prospered, first in the old South, later in Cincinnati. As for my father, born in Warsaw, he began his career studying conducting in Berlin in the late 1920s—and he would have been killed by the Nazis had he remained there. But having been lucky enough to obtain a United States visa in 1933, he went on to create a new life here. Didn’t I, his son, owe this country something in return?

The American Dream felt very real to me. After my graduation from Harvard, followed by a year of travel in Europe on a fellowship, doors opened rapidly. All over the United States, regional opera companies popped up, eager to present productions with dramatic coherence. At age 22, a very young opera director, I found the transformed landscape thrilling; I foresaw a future of limitless possibility. How could I turn my back on it?

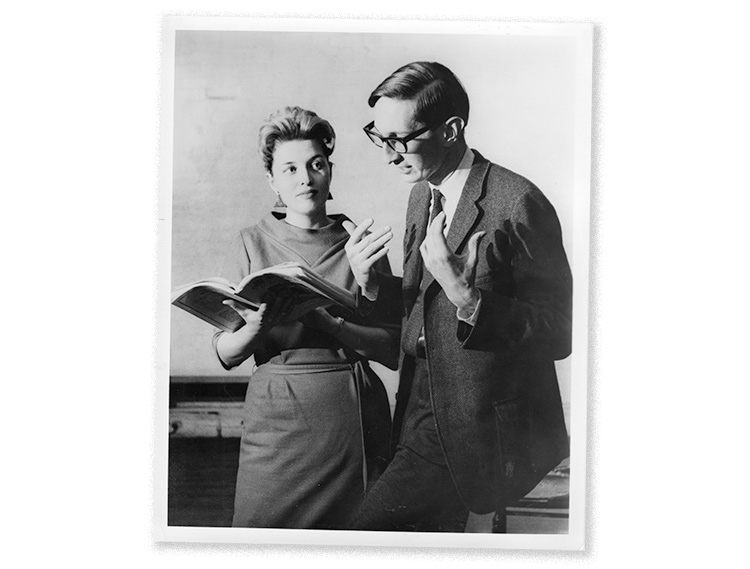

Opera whiz at work. The author, age 24, two years before being drafted, “directing” the soprano Carolyn Heafner in Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio, produced by the Turnau Opera, 1964.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

But after struggling for months with the pros and cons, I answered my country’s call. My local draft board ordered me to report in April 1966. When I informed them that I was scheduled to stage a major production at the Juilliard School in May, they very obligingly postponed my induction to June. The resulting show, an epic staging of Roger Sessions’s The Trial of Lucullus, was crucial to my future career. Its exceptional success led to numerous productions with regional opera companies and launched an unforgettable collaboration with the revolutionary Italian composer, Luciano Berio.

My good luck continued. Not long after Lucullus opened, my mother, very much a social butterfly, bumped into a distant acquaintance—Jean Dalrymple, the director of theatrical productions at the New York City Center—at a midtown cocktail party. Their casual conversation turned earnest when Mom confessed that she was extremely concerned about me, as I was about to start basic training.

Ms. Dalrymple asked if she knew where I’d be sent. Fortunately, amazingly, Mom did. She told her I was headed for Fort Gordon.

“Alma, what a coincidence,” Ms. Dalrymple reportedly said. “My husband, General Ginder, knows General Richardson, the commanding officer there, very well. He’ll ask him to look out for your son.”

I was dubious when Mom told me; this offer sounded like empty cocktail chatter. Why would Jean Dalrymple’s husband urge his wartime buddy to help a kid he never met? And why would his buddy agree?

But it happened. General Ginder did as his wife promised, and his longtime pal came through. My hat is permanently off to Major General Walter B. Richardson, who was Fort Gordon’s commanding officer. Thanks to his direct orders, I spent all of my military service Stateside, under his command as a noncommissioned officer in Special Services.

But even though I’m eternally grateful for it, my escape still troubles me. What about the hundreds of thousands of poor devils without my luck and connections, who were sent to the hellhole of Vietnam? This all but miraculous piece of good fortune, so easily obtained, has haunted me ever since.

Ian Strasfogel is an author, opera director, and impresario who has staged over a hundred productions of opera and music theater in European and American opera houses and music festivals. His comic novel, Operaland, and his biography of his father, Ignace Strasfogel: The Rediscovery of a Musical Wunderkind, were both published in 2021.

Other articles by Ian Strasfogel:

A Kerfuffle Over the Andarz Nama, an Ancient Persian Miniature

To Restore or Not to Restore a Rare Einstein Photo—It’s All Relativity