ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Trailblazing Women in the Mad Men Era

Triumphing over gender discrimination during the 1960’s.

By Dorri Olds

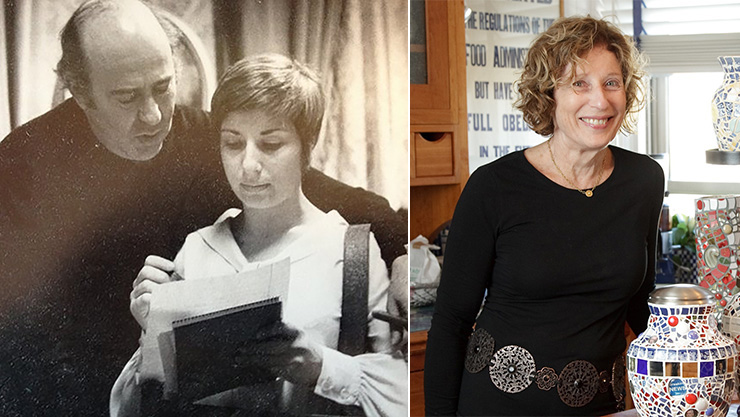

Marcia Gloster on right, and in 1969.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

An Ad Agency of Her Own

Marcia Gloster’s new novel, I Love You Today, is the story of a young woman in the 1960’s who manages to challenge and overcome gender discrimination, based largely on Marcia’s own experiences. After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in the 1960’s, Marcia’s dream was to work in the art department of an ad agency. But recruiters warned her that despite her art degree, she’d never be more than a secretary or receptionist. At one Madison Avenue agency, she was told she couldn’t be hired because the boys in the bullpen would feel “too self-conscious” to swear in front of a “girl” and, therefore, their work might suffer. Her answer: “I can swear. Want to hear me?” She didn’t get the job, but she kept looking, taking any freelance gigs she could find.

“The show Mad Men is wonderfully evocative of my early days in Manhattan,” Marcia says. “The word discrimination wasn’t even in my vocabulary back then. Finally, after interviewing extensively, I was hired as an assistant art director at Brides Magazine in 1964.” But she kept looking for better jobs. “One boss at an ad agency where I was working liked to walk potential advertisers past the art department whispering, ‘Have a look at my art director.’ Did he think I didn’t hear him? Men were condescending, crass, chauvinistic and dismissive.”

Finally, in 1977, a client offered Marcia his ad account with the stipulation that she set up her own business. The offer got her attention. “It was unheard of in those days for a woman to start her own ad agency,” Marcia said. “But I just called a lot of people, asked for advice, and somehow, I did it.”

In 2011, Marcia wrote her first book, 31 Days: A Memoir of Seduction. She laughed, recalling “I had never written anything other than client proposals and marketing plans, but I wrote the story of my summer in Salzburg 1963, which I spent with a British painter. As I wrote, I also began painting again. Joy and energy surged into my life and I felt 20 again.”

These days, Marcia lives in New York City and Verona, New Jersey, with her husband. They have one daughter, a grandson, and a granddaughter on the way. And she has just finished her second novel and continues to paint. But she is still dubious about our current world. “Despite the woman’s movement, a lot hasn’t changed for us,” she said. “Will women ever be free of snide comments and misogyny? That’s like asking, ‘Will there ever be peace in the Middle East?’ It’s shameful that these views still exist among some men. No government should control what a woman can do with her life or her body. It’s as if we’re returning to a medieval mentality and will soon be told to wear chastity belts.”

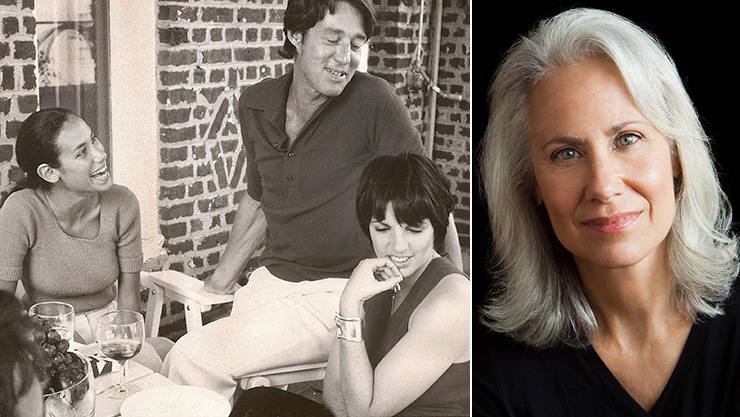

Left: Carl Reiner and Sybil Adelman Sage in 1977. Courtesy of Sybil Adelman Sage.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A Comedy Troublemaker

Sybil Adelman Sage was one of the first women to break into comedy TV writing. After graduating from NYU in 1963 with a degree in psychology, there were no jobs available so she became a secretary. After a series of uninspiring temp positions, Sybil finally found another job—also secretarial—but this time it was for the renowned producer Carl Reiner and he was a kind boss. Still she yearned for a more meaningful perch. Her horizon widened when, in 1970, the Mary Tyler Moore Show aired. Produced by Jim Brooks and Allan Burns, it was the first TV series starring a never-married, independent career woman. “I was encouraged by the show,” says Sybil. “I saw that women didn’t need to feel embarrassed about having ambitions. But it took a lot of chutzpah to believe I had the right and ability to write a script.” But since agents met frequently in Reiner’s office, Sybil figured she and her female co-author had a shot at getting their script read. Reiner not only read the script; he was so impressed that he asked the two-some to come up with ideas for The New Dick Van Dyke Show.

Producers Brooks and Burns were ahead of their time since they felt that women brought a deeper understanding to the show. “The MTM series helped those of us who became writers in the 70’s,” says Sybil. “We were seen to have value.” Even so, the network credited male writers as the authors—until Norman Lear set things right. “Lear was an über mensch,” recalls Sybil. “He got our names on the script.”

Sybil knew that she was lucky to be working with powerful men like Reiner and Lear. She recalls one afternoon when she was kept waiting far too long for a scheduled meeting with a producer who needed a writer. “Nobody apologized or explained,” said Sybil. “I called my agent and said, ‘I’m about to leave.’ ‘No,’ he said. ‘The producer is my client. I’ll call him.’”

The producer finally came out but, Sybil recalls, “with a tone you’d use with a toddler or dog,” he said, “Are you the one causing all the trouble?” Sybil retorted: “I was here on time. You’re the one who kept me waiting!” She felt strongly that he would not have been condescending to a man and she left. Soon after, another producer asked her to write a pilot for a new show. “I’ll give you $30,000” he said. Then, loud enough for Sybil to hear, he offered to pay a male writer $35,000. Sybil retorted: “Why would you give him more?” He answered: “Because he’s a man.”

After that incident, Sybil wrote an episode of Alice starring Linda Lavin as a waitress at Mel’s Diner. Alice and two other waitresses went on strike after discovering that Mel had hired a man and was paying him more. “I was paid for my work,” recalls Sybil. “But the male producers never shot it.” The episode finally aired when a new producer duo came on board—a man and a woman.”

“My career reminded me of being single and waiting for a guy to call,” she recalls. Fewer and fewer job offers were coming in. “This time it wasn’t sexism,” she admits. “I think it was my age. The writing was on the wall and it wasn’t by me.”

So Sybil switched gears and began selling articles to popular women’s magazines like Redbook, Glamour, Working Woman, Good Housekeeping and Family Circle. She is still publishing essays and hopes to resurrect them for a memoir she is working on “lazily and leisurely.” She also writes comedy for Lily Tomlin’s shows and is recognized as a trailblazer in the 2006 book, Feminists Who Changed America, 1963–1975. In 2008, Sybil turned her former hobby of collecting pique assiette mosaic art into an online business called sagemosaicart.com. “I thought it would be a piece of cake,” she said, “unaware of all that’s involved: photo-editing, working with web designers, optimizing the site, shipping, and getting scolded by the FedEx lady.” But she met the challenges and has built a nice business.

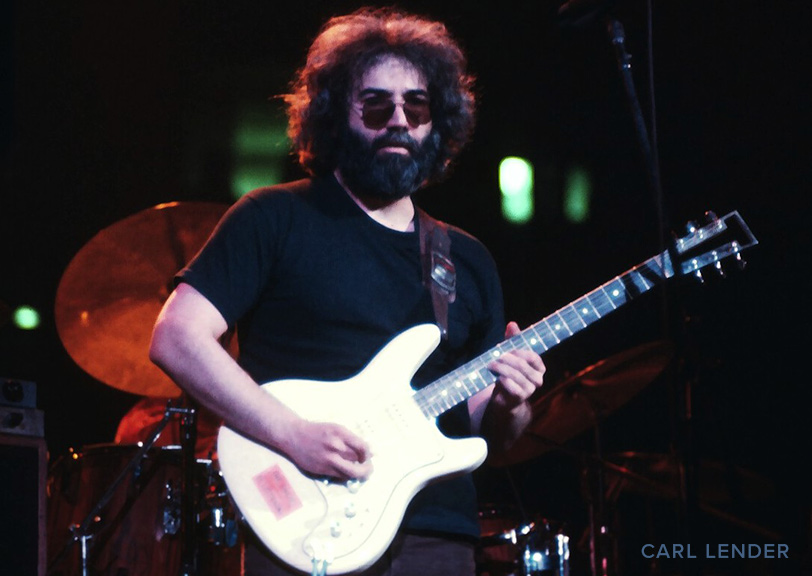

Lynn Povich interviewing Halston and his client Liza Minelli in 1972, photo by Newsweek. Right: photo of Lynn Povich by Christian Steiner.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Good Girl Revolutionary

Lynn Povich is an award-winning journalist who spent more than 40 years in the news business. As many know, she was also one of the women journalists who filed sex discrimination charges against Newsweek in 1970. Soon after the suit was settled, Newsweek promoted her, making her the first female senior editor in Newsweek’s history. Lynn’s book, Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued Their Bosses and Changed the Workplace (2012), describes the trials of women who worked at Newsweek in the late 1960’s. Yet Lynn says she never felt that the discrimination was personal. “It was institutional,” she explains. “Only men were hired as reporters, writers, and editors. Women were hired as researchers, rarely promoted, and many have horror stories. We all shared psychological imprisonment of our hopes and desires.”

Lynn continues: “We were all raised to believe that our role in life was to marry, raise children and take care of our husbands. Breaking out of that mind-set was more difficult than speaking out against harassment or discrimination. I don’t think we could have done it without the women’s movement, which supported our revolt. And due to the civil rights and anti-war movements people began thinking differently about equality and authority. You can see that evolution in Mad Men. Peggy and Joan push ahead in their careers, but they pay a price.”

When Lynn’s book was published in 2012 she received inquiries about turning it into a film or TV series. But when her lawyer said she’d have no creative control over the project, she turned them all down. A year later she got a call from Lynda Obst, the successful producer of Sleepless in Seattle. “I knew Lynda when she was an editor at The New York Times in the ’70s. She understood that era. I gave her the option if she agreed to fictionalize the series.” She agreed. A 10-part series was shown on Amazon Prime in 2015.

“The characters were all fictional,” says Lynn. “There is no “me,” but the arc of the story is accurate. It’s about a group of women at a news magazine, who become conscious of injustice and begin to organize a sex discrimination complaint against their bosses. The best thing about the series is that an entire generation of younger women and men watched it. They learned what it was like for women of my generation and it convinced many of them that they too can change the system.”

So how much has changed for women? “We’ve made a lot of progress in career advancement,” says Lynn. “Women are solidly in senior management roles. But we’re still not running things. Less than five percent of Fortune 500 CEOs are women, roughly a quarter of full professors are women, nineteen percent of Congress members are female and fifteen to seventeen percent of the Corporate Suite officers are women. And even though almost half of the graduates in schools of law and medicine are women, the majority of women who work in these fields are not in top positions.

“Young women, who didn’t want to be identified as feminists, are now realizing that the fight isn’t over,” says Lynn. “We’re not ‘post’ feminists. The silver lining to Trump’s election is that young women are finally realizing that their options and freedom are at stake—and they are angry, organizing protests and, according to Emily’s List, 10,000 have decided to run for office.”

This Mother’s Day, let’s keep in mind that these young women are the children of a generation of fighters who raised social consciousness about inequality in the workplace. Despite the setbacks of our current political climate, we cannot give in to despair. Marcia, Sybil and Lynn didn’t curl into a ball and accept the limited options presented to them. Instead, the obstacles they encountered ignited the fuel that exploded into resistance—we can learn from them and fight for our freedom to succeed.

Dorri Olds is a freelance journalist and social media coach.

May 11th, 2017 at 10:48 am

I was not adventourous as these wonderful women. Great story. I will share it Mother’s Day with daughters and granddaughters — and all the men in our family

August 11th, 2017 at 8:28 pm

Enjoyed reading it again. You’re pretty amazing yourself Dorri.