ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Three Days With Gregory Peck

Years ago, The Ladies Home Journal sent me to Beverly Hills to interview Peck. I spent three memorable days with him, as he talked openly about his career and his life. What a treat!

By Barbara Lovenheim

Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

I was a teenager when I became aware of Gregory Peck as one of the top screen actors in Hollywood, revered for his ability to play heroic figures with enough candor and humor to make them credible. But it never occurred to me that I would have an opportunity to meet Peck or interview him. Oddly enough, the opportunity materialized on a visit to my hometown, Rochester, NY in the fall of 1988. I happened to read in the local Gannett newspaper that Gregory Peck was about to receive the annual George Eastman Award for distinguished contribution to the motion picture industry. The award was founded in 1955 and had been awarded to many Hollywood giants, including Lillian Gish, Fred Astaire, Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep.

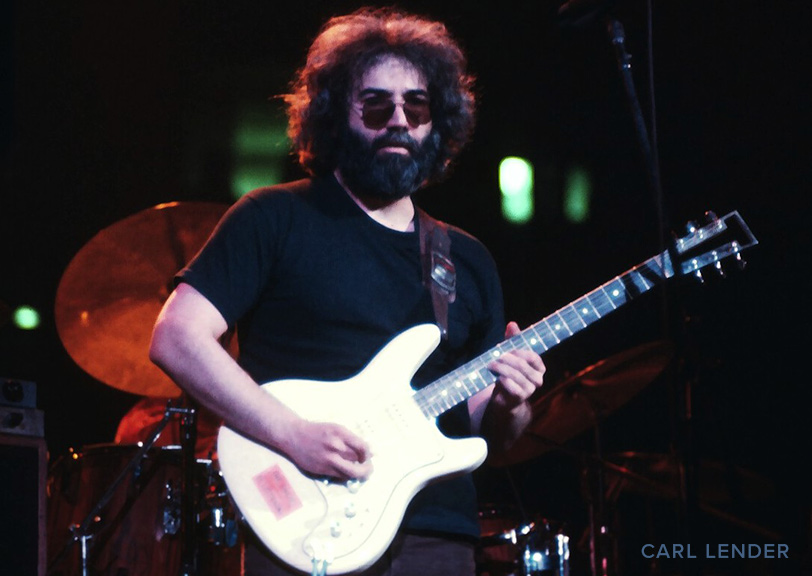

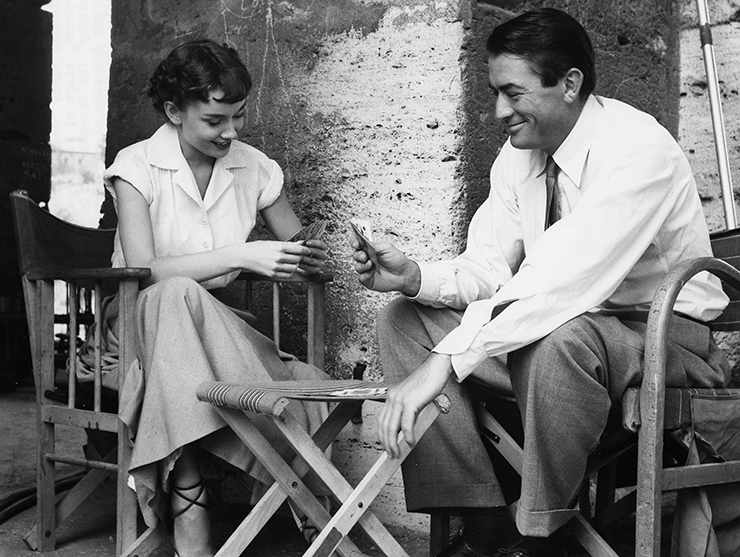

I immediately bought a ticket. I hoped that if I met Peck, then in his early 70’s, he would agree to an interview with me. He had already won an Academy Award for his masterful portrayal of Atticus Finch in the tour de force To Kill a Mockingbird. That Saturday evening I sat in a small film theater awaiting the arrival of the host—within a short time the MC opened the event with a surprise announcement: Audrey Hepburn was on hand to introduce Peck. The small audience broke out into applause as she walked out in one of her signature black dresses. Slender as a rail and beaming with her iconic smile, she walked to the microphone to begin her introduction.

When Peck appeared he kissed her on the cheek and waved to the crowd. It was all delightful. Peck and Hepburn together again—in, of all places—Rochester. After the ceremony and clips from his various films, I stood in line to pay my respects to Audrey, who was thoroughly gracious. Her companion—Robert Wolders, a Dutch television actor, had a sister in Rochester so he and Audrey decided to make the trip. After standing in line to meet the duo, I asked if he would be amenable to an interview. He gave me a phone number to call in L.A. I was thrilled.

When I returned to Manhattan, I called my editor at McCalls, but for some peculiar reason, she was not interested in a Peck interview. I was truly surprised since Peck rarely granted interviews, so I immediately called Myrna Blythe, the editor-in-chief of The Ladies Home Journal. When I told her I might be able to snag an interview with Gregory Peck, she immediately gave me an assignment. The magazine would send me to Beverly Hills for three days and put me up at the swanky Beverly Hills Hotel on Sunset Boulevard aka The Pink Palace, a watering well for royalty, celebrities and film stars galore. I immediately called Peck’s office in L.A. and his secretary got back to me promptly; he would be pleased to do an interview.

Several weeks later I arrived in LA in late afternoon. I spent the better part of the next day reviewing my notes; at 3 pm I was driven to Peck’s home in a secluded and very swanky area of Beverly Hills, where many film stars lived. His house was set high on a hill, protected from the road by high hedges and a long, winding driveway manned by a security guard. When I arrived at the front door, Peck, towering over me at 6’3″, greeted me. Dressed casually in chinos and a green sweater, his thick hair a silvery white, he was simply magnificent. After quickly shaking hands, he walked me into a huge living room lined with shelves of history books, Victorian novels, a leather-bound set of Peck’s movie scripts and a large Japanese print. In one corner there was a large and handsome grand piano. In the middle of the room there were four large couches—two each back to back—enough room for many visitors. The windows overlooked a patio and acres of green manicured grass that led down to a tennis court and a swimming pool. A very large dog stood quiet guard in the middle of the room.

Before the interview we took a detour into the kitchen—large and tiled with a mock terra cotta floor and a set of gleaming copper pots, pans and cooking utensils that hung from a rod overlooking a tiled worktable in the middle of the room. Then we wandered into the living room, where Peck sat in a deep leather chair in the corner. I sat facing him in a comfortable, but smaller chair. Everything about Peck was larger than life, including his gracious and inviting personality. Not bad for a kid whose parents split when he was three years old and who never knew what it was like to live in a stable family.

“Maybe I’ve been reticent in the past,” he said pensively, “but I’m 72 years old now and I can say anything that I please. And I’d rather be a bit more revealing. My heart goes out to people—I want to understand them and I want them to understand me.” To understand Peck you have to understand his turbulent childhood. Gregory was born in St. Louis. His father was of Irish descent and worked in La Jolla, a small town in California near San Diego, as a pharmacist. “He always had just a touch of an Irish accent,” Peck said with a smile. “Father couldn’t pronounce ‘film’—he would say ‘filme.’ But when he was 75 and had a full head of white hair (and Peck was already a film star) father would say, ‘Ah yes, but I’ve not been at all well lately.’”

“Bunny,” Peck’s mother, was born in St. Louis, Missouri. But the marriage was rocky from the start and after three years they separated. Bunny took Gregory back to her hometown where they lived with her mother, who ran a seedy boarding house. Gregory made lemonade, which the boarders would lace with gin; he shined shoes, he sold lemonade for a nickel a glass, and he hawked newspapers on the street corner.

“My memories of stress and hardship go way back,” he explained, as he recalled these early years. “I did a lot of bouncing around and had a feeling of being different or alone, but most people never imagine that I went through anything like that because they see me as an ‘establishment’ person.” Eventually Bunny bundled up Gregory and moved to San Francisco to share a house with Bunny’s brother and his family. But the arrangement didn’t work. So they bounced back to La Jolla and Bunny got a job waiting tables. But she disliked the job, parked Gregory with his paternal grandmother and went off to L.A, where she got a job as a receptionist. Eventually she remarried and settled in San Francisco.

“That began a happy time,” Peck continued. “We lived in a redwood bungalow. My father scraped up money for a bike and I found a black and brown mixed breed dog and named him ‘Bud.’ My grandmother was a terrific cook; I knew everyone in town; I was free on my bike. I remember watching Civil War vets dressed in the blue and grey marching down the street to a band—it gave me a connection to an America that was more individualistic—when people were rugged and had opinions and stuck by them.”

At age ten he was sent off to a Catholic boarding school, where he learned how to compete and win prizes. “It was reward and punishment,” he recalled. “And I went for the whole ball of wax. I worked up to the rank of cadet caption and learned that if you worked hard and got along, you were rewarded with emblems.”

Then life turned sour: His grandmother died and he moved in with his father. “I loved my father,” he said, “but he worked nights and we lived in a colorless shabby house that was quite often empty. I wasn’t a hot shot in school—I was quite withdrawn and felt lonely and out of place. I never remember sitting down to dinner with my whole family.”

Eventually he enrolled in San Diego State Teacher’s College, but disliked the school. A year later he enrolled at Berkeley as a pre-med student. There he adopted the liberal creeds that were rampant on the campus in the early 1930s; he waited on tables, worked as a carhop to pay for his room and board, and almost ran off to fight against Franco in Spain, but decided to stay and finish his course work. Eventually he switched his major to literature because he was “miserable” doing math and science and, after performing in a number of campus productions, he decided to make his way as an actor.

He resettled in New York City, working as a barker at the World’s Fair and an usher at Radio City Music Hall to earn his keep. Then he managed to win a scholarship from the Neighborhood Playhouse in Manhattan and he spent the next five years performing in summer stock and national road companies—doing mostly comedies—and playing bit roles on Broadway. He didn’t even consider entering the film world until a producer saw him on the stage and immediately offered him a role in Days of Glory. Male actors were in short supply at the time due to the escalating conflict overseas and need for soldiers, but Peck was exempt from military duty due to a back injury. Even so, he wasn’t thrilled with the opportunity. “I wasn’t interested at all,” he told me. “I wanted to be a stage actor. But I was in debt somewhat; I’d gotten myself married [to Greta Kukkonen, a hairdresser he met on a road tour]; we had three sons and we lived in a ratty little flat. So when Casey Robinson offered me $1,000 a week, I accepted because that was real money!”

When the film was released in 1944, it was a dud, but Peck’s performance and resonant voice earned him praise. Even though the need for soldiers was halting, Peck became a hot property: He had the looks, the voice and the intelligence to make it all work. Within a year he was one of the top ten box office draws in Hollywood; during the next five years he won Academy Award nominations for his roles in Keys of the Kingdom (1944), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and Twelve O’Clock High (1949).

Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck on the set of Roman Holiday, 1953.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

As Peck continued to climb, he stuck to his guns and went his own way, rarely giving interviews or attending the showy Hollywood parties that engulfed other stars, becoming known instead as a hard-working, diligent and somewhat reclusive actor. Part of his solitude was due to his separation from his first wife and the pressures on him to support her and their sons. Then the personal aspects of his life took a significant upturn in the early 1950’s, when he went to Italy to film Roman Holiday with Audrey Hepburn. En route he stopped in Paris, where he had accepted an interview with a French journalist named Veronique, a slim, petite Parisian in her twenties.

Back in Italy rumors swirled that Peck and Hepburn were romantically involved: It an issue he skillfully skirted. “With Audrey it was very easy, under the circumstances, to fall a little bit in love and have very tender protective feelings about her,” he said without blanching. “Audrey was so new and we all had the feeling that we were doing something that everyone would enjoy. And, being the simple folk that we are, that’s all it takes to make us happy. In our case we were both using our emotions and our intelligence and everything that we had to make a believable and identifiable picture. It’s wonderful to remember.”

Whether or not there was a romantic liaison is now academic; a few months later Peck was in Paris again and called Veronique to make a dinner date. “Everyone in the newsroom was stunned when he called,” Veronique told me when I met her after one of my afternoon chats with Peck. “He asked me to lunch, but I had an interview with Albert Schweitzer so I offered to meet him later in the day. At 3:30 Dr. Schweitzer was still having meetings and I had to decide whether to keep my interview or keep my date. I decided to keep my date, and now I kid Gregory and say, ‘If I’d kept my interview with Dr. Schweitzer, I might be a widow in the Congo today!’ Peck managed to get a divorce from his wife two years later and married Veronique. They moved to Hollywood, established an elegant home and had two children, Anthony, now an actor, and Cecelia, an actress and producer.

Peck’s marriage to Veronique was a stabilizing factor in his life and from all accounts they both thrived. During the 1950’s and early ’60s Peck continued to star in blockbusters, including the epic western The Big Country (1958). But it was one of his next films—To Kill a Mockingbird—that became his favorite because he identified so closely with the endearing and earnest lawyer Atticus Finch, who took on the burden of defending a poor black man accused of raping a young white girl.

“It was as close to me as I can ever get on the screen,” he said with the earnestness we have come to identify with Peck. “I looked forward to rehearsals every morning. I was a kid very much like the two kids in film; I even used to roll down the street of our town in a rubber tire. And it gave me a chance to say in a dramatic and entertaining way that there was serious racial injustice in the south in 1931; it was in the air in the early ’60s with the battle for civil rights. We all believed very much in civil rights reform and legislation to protect the rights of the blacks; it was our chance to have our say in a non-soapbox way.

When I returned to New York City I was filled with enthusiasm about my interview with Peck and quickly submitted the article to The Ladies Home Journal. A few days later I received a call from my editor: She had distressing news. Despite Myrna’s clout as a top editor, the magazine would not run the article because, she told me, there was not enough material about his lunches with Hollywood actresses.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: After sending me to Hollywood to interview one of the top actors in the U.S., the magazine editors were killing my article because I didn’t write about Peck’s lunch dates with other Hollywood stars? Yikes! But there was nothing I could do—when I tried submitting the manuscript to other comparable magazines they didn’t want it. Some time later I finally got the low down: Peck was a political liberal, but the owners of the magazine were hard-nosed Republicans, who refused to run an upbeat article about Peck. Why? They disagreed strongly with his political views and didn’t want to advertise them. And so my Peck article never saw the light of print—until I recently decided to retrieve it and post it for the legions of readers who are fans of Peck.

Meanwhile drama enthusiasts will also be happy to know that after months of controversy revolving around Aaron Sorkin’s upcoming Broadway version of To Kill A Mockingbird, the Broadway adaption will proceed as originally planned. Gregory Peck, who in the film version played the role of Atticus Finch, would sure be happy!

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Lovenheim, founding editor of NYCitywoman.com, has written on lifestyle and the arts for The New York Times, New York, The Wall Street Journal, and many major magazines. She is the author of Survival in the Shadows: Seven Jews Hidden in Berlin and other books.