ENTER YOUR EMAIL TO RECEIVE OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

Calder in Motion at the Whitney

With patience, intense dedication and deep dives into Calder’s skills and history, research conservator Eleonora Nagy brings the artist’s mobiles to life, setting them spinning, whirring—and, occasionally, colliding.

By Suzanne Charlé

Untitled, 1947, Sheet metal, wire, and paint, 27 1/2 × 27 1/2 × 9 in. (69.9 × 69.9 × 22.9 cm), Calder Foundation, New York. Images courtesy of the Whitney.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

“Why must art be static? You look at an abstraction, sculptured or painted, an entirely exciting arrangement of planes, spheres, nuclei, entirely without meaning. It would be perfect, but it is always still. The next step in sculpture is motion.”

Almost nine decades after Alexander Calder answered his own question and took “the next step in sculpture,” the Whitney Museum of American Art presents Calder: Hypermobility, an exhibition that spins with creativity, wit and wonder. Mounted in collaboration with the Calder Foundation, the show highlights Calder’s early, lesser-known motorized sculptures, in addition to his famous wind-driven mobiles.

Calder’s moving artworks have fascinated viewers since he first started making them in Paris: Marcel Duchamp was so intrigued, he gave them their name: “mobile,” a clever pun which in French means both “motive” and “that which moves.”

In recent exhibitions, however, Calder’s mobiles have been static. Curators typically kept them frozen, concerned about their fragility; that, plus the fact that most motorized mobiles (only 44 exist today) simply weren’t working.

But curators at the Whitney were determined to present a show in which the mobiles moved as Calder intended. Over the past year, they worked with Sandy Rower, head of the Calder Foundation, and Eleonora Nagy, the conservator who inspected all the mobiles to make sure they could move safely.

A number, many of which last moved when the artist was still alive, required significant investigation and conservation: “It was rather like forensics,” Nagy says. And, as in any good mystery, the experts’ expectations were often confounded. “I was completely surprised,” said Rower, who as grandson of Calder, grew up surrounded by many of the mobiles. “You have to ask yourself a whole series of new questions.”

Now, sixteen suspended mobiles, plus eight motorized mobiles, spin, whir and, in some cases, collide and gong to Calder’s plans, thanks in large part to the efforts of research conservator Eleonora Nagy (at right, repairing the Calder mobile “Seascape”). Trained museum technicians “activate” the mobiles three times on weekdays and six times on the weekends, giving visitors a chance to watch the mobiles and their unpredictable dances, eight floors above the city. To make certain the technicians moved the mobiles correctly, videos were made: “A document from the horse’s mouth,” says Nagy.

Now, sixteen suspended mobiles, plus eight motorized mobiles, spin, whir and, in some cases, collide and gong to Calder’s plans, thanks in large part to the efforts of research conservator Eleonora Nagy (at right, repairing the Calder mobile “Seascape”). Trained museum technicians “activate” the mobiles three times on weekdays and six times on the weekends, giving visitors a chance to watch the mobiles and their unpredictable dances, eight floors above the city. To make certain the technicians moved the mobiles correctly, videos were made: “A document from the horse’s mouth,” says Nagy.

Conservation of three-dimensional modern art was a new field in 1995, when the Guggenheim hired Nagy, who trained as a conservator in Budapest (because of World War II and the Soviet invasion “we had much to work”) and later in Canada and at the Tate. There were a number of issues that were unique to Calder’s mobiles, some of which were in very poor shape: “Unlike oil on canvas, there was no paved road as to what to do.” Nagy had to invent protocols for how to transport the mobiles and how to make them move: “What were the issues? What was wrong? The questions were inspiring to me.”

“Calder was an exceptional artist,” notes Nagy, who is now research curator at the Whitney, in addition to proprietor of her own firm, Modern Sculpture Conservation, in Red Hook. “He was trained as an engineer. When he created a mobile, he looked for the most elegant and simplest solution.”

However, she says, the artist wasn’t necessarily elegant in his choice of materials: “Any junk he found: leftover wood, wire from India, cotton thread—always the cheapest.”

Calder was always experimenting: “His ideas were beautiful, sharp, clear—but the rest was sloppy. Once he was finished, there was no clean up! He would never put primer on. Just on to the next piece!”

For this exhibition, curator Jay Sanders suggested what pieces he would like, and then Nagy and he would go back and forth: Could the piece be properly restored and moved without endangering the work? Could it be repaired in time?

“Half-circle, Quarter-circle, and Sphere,” 1932, one of the earliest motorized pieces, hadn’t worked in years. How fast had Calder meant it to run? Turns out, the motor was fine, but “little gadgets had gotten tilted.” The mechanism was completely rebuilt, “bit by bit,” and the movement was clear: A beguiling pas de deux, created by Calder intentionally downscaling the capacity of the motor. As for the base: the paint was obviously not original. When there’s time, Nagy “will need to go down 11 layers” to get to the truth. Why? No slave to consistency, if a piece of paint chipped off, Calder—or one of his friends—would just paint over. (In “Square” (below), 1933, a bright green was found under layers of yellow paint. Calder’s dealer had repainted it, says Rower, because “yellow is a Calder color.”)

Other works required re-engineering. No one could remember when “Machine motorisée” (below), 1933, last moved, but it looked as if the brown club-like wooden shape was going to spin like a top next to a black form. After Sandy Rower unearthed the original (totally dead) French motor at the Calder Foundation, Nagy commissioned a specialist to take it apart and put it back together; she engaged another specialist to hand make a new metal pulley. Two weeks before the show was to open, says Nagy, they switched on “Machine motorisée.” “Hallelujah!” But the brown club did nothing. “Nothing!” Then suddenly, the brown piece bent forward, just touching the black: “Just like a kiss.” Was something wrong? Nagy and the specialist double-checked to make sure the tiny engine was running in the right direction. It was. The team turned it on again, and again the hesitant kiss. The kiss was confirmed.

“You can’t anticipate the movement until it’s restored,” said Sanders, the curator. “With every single piece, our predictions were defied.” Some move so slowly, Sanders compared them to Minimalist music and dance—which came decades after the earliest motorized mobiles.

The wind-propelled mobiles also required attention. In stringing the pieces, Calder often used cheap cotton thread, which meant that in time, the mobiles had to be restrung, often by people who had no idea of the complexity of Calder’s knots.

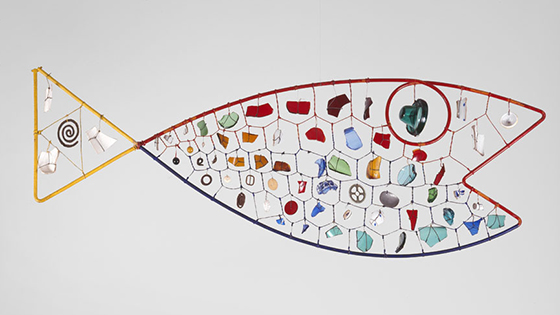

Nagy, who over the decades developed what she refers to as a “lexicon of Calder knots,” immediately spotted the imposters. In “Fish” (below), 1944, bits of colored glass, beads and mirrors now shimmer like fish scales in the slightest wind. Nagy reworked the strings—some of which had been replaced, others that were original but likely to break. In the aging originals, Calder’s engineering skills were evident: “He was very particular about the thickness of the string,” recognizing that it would impact the way the mobile worked.

In “Seascape,” 1947, it was clear that the strings used were not original: “They weren’t twisted, the knots were all wrong—and besides, Calder often left ends of the ties.” Old photos of the piece suggest that Calder remade “Seascape” with fewer rods and elements.

The present-day dimensions didn’t match the photos, taken from many different angles. Eventually, Nagy extrapolated the dimensions from the old images and brought the mobile back to life, “bit by bit.” “He would twist and twist the string by hand and then carefully knot it.” Calder, she explains, “made a system of knots,” sometimes making knots to the left and to the right, “creating a mirror image…. Sometimes it takes days to figure out.”

Inevitably, reconstructing the intricate movements planned by Calder led to surprises: “It was loads of fun to do,” Nagy says. In some, the artist orchestrated collisions, creating sounds, such as “Red Disc and Gong,” 1940, and later “Triple Gong” (below), 1948, with its small metal cylinders randomly striking three brass gongs—a sonorous technique Calder continued to explore into the early 1960’s.

“Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions,” Calder said. Thanks to the Whitney’s Calder: Hypermobility, we can now see and hear his moving compositions in action.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Calder: Hypermobility, at the Whitney, through October 23, 2017. There is an audio guide, complete with a musical score by jazz artist Jim O’Rourke. For detailed information, see: Calder: Hypermobility Activations and Performances.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Suzanne Charlé has written for numerous publications, including the Nation, House Beautiful, and The New York Times, where she was a freelance assigning editor for the magazine. She has co-authored many books including Indonesia in the Soeharto Years: Issues, Incidents and Illustrations.

July 12th, 2017 at 2:02 pm

Saw the show two days ago (on time for the waving of the wand that sets pieces in motion, thanks to my ace researcher sister-ex-law); was elated; thought I knew all I needed to know to appreciate Calder’s genius. Suzanne’s wonderful piece enriches the memories & makes me want to hurry back, equipped to look with smarter eyes. Thanks!

September 7th, 2017 at 8:37 am

Thanks, Suzanne, for this great article. Looking forward to seeing the show next week.